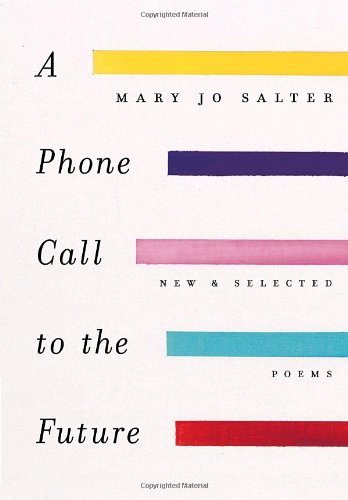

Superb new poems from one of the major poets of her generation, along with a selection of the best from Mary Jo Salter’s previous award-winning collections. In Mary Jo Salter’s poetry we have a unique blend of domestic drama and the grittier wider world. In the title poem, she reimagines the technological simplicities and humanistic verities of the past with a brilliantly disorienting detachment. Here are poems imbued with the violence of modern life—a mother slapping her child on the subway, a child losing everything in the Iraq war—and others that bring a witty luminosity to peacocks in the park, to shoe-shine “thrones” at the airport, and to poetry itself. A tender elegy for the poet Anthony Hecht is followed by poems about the Baroque sculptor Bernini and the German Expressionist painter August Macke, which add to Salter’s already impressive list of poems about image-making. Although in many of the poems Salter looks back wistfully at what is lost, she also sets her sights on the future: "Lord, surprise me with even more to miss," she writes in “Wake-up Call.” Among the selected older poems are the much-anthologized “Welcome to Hiroshima” and “Boulevard du Montparnasse”; her historical narrative “The Hand of Thomas Jefferson”; and moving elegies for her mother (“Dead Letters”), her friend (“Elegies for Etsuko”), and her psychiatrist (“Another Session”). Here, also, are such light verse delights as “Video Blues” (“My husband has a crush on Myrna Loy”) and “A Morris Dance”; poems that bring a deeper insight into foreign settings and cultures (from “Henry Purcell in Japan” to “Icelandic Almanac” to “The Seven Weepers,” set in the Australian outback of 1845); and poems that reflect on the art of seeing, as in “Young Girl Peeling Apples” and “Trompe l’Oeil.” A Phone Call to the Future is a powerful reminder and a ringing confirmation of Mary Jo Salter’s remarkable gifts. “Only a few poets transcend the history of taste to participate in the history of art–and only in a handful of poems. Salter has been struck by lightning more than once… ‘Another Session’ is, like “Elegies for Etsuko,’ a disorienting work of art.” —James Longenbach, The New York Times Book Review “Celebrated since the 1980’s for her deftly articulate, often wittily rhymed lyric poems, Salter demonstrates those strengths and others in this sixth volume . . . Salter may be the most gifted mid-career disciple of James Merrill’s work . . . yet her loosely syllabic stanzas owe as much to Marianne Moore, and her best poems stand apart for their careful sensitivity both to works of art and to her own family life.” — Publishers Weekly “Marked by a very conscious sense of craft, Salter’s work is precise and artful, composed with a decided sensitivity toward formal poetic tradition . . . There are no extraordinary events here, just the business of day-to-day living, with its little highs and lows, recounted in poems that are deeply human, brilliantly realized and refreshingly perceptive.” —Julie Hale, Bookpage Mary Jo Salter was born in Grand Rapids, Michigan, and grew up in Detroit and Baltimore. She was educated at Harvard and Cambridge and worked as a staff editor at The Atlantic Monthly and as poetry editor of The New Republic . She is also a coeditor of The Norton Anthology of Poetry . In addition to her five previous poetry collections, she is the author of a children’s book, The Moon Comes Home, and is a playwright and lyricist. After many years of teaching at Mount Holyoke College, she is now Professor in The Writing Seminars at Johns Hopkins University. She and her husband, the writer Brad Leithauser, divide their time between Amherst, Massachusetts, and Baltimore, Maryland. WAKE-UP CALLThe water is slapping wake up, wake up , against the boat chugging away from Venice, infinite essence of what must end because it is beautiful,Venice that shrinks to a bobbing, pungent postcard and then to nothing at all as the automatic doors at the airport obligingly shut behind you.Re-enter a world where everything’s much the same, where you’ve gone slack again, and don’t even know it, so unaware that you actually shrug to yourself, I’ll be back , and yes, for some lucky stiffs it’s true, sometimes it’s you, you’re sure to get more chances at Venice, and Paris, and that blessed, unmarked placewhere you sat on a bench and he kissed you that first time, so many kisses, you hoped he would never stop, you can hope, at least, not ever to forget it,or forget how your babies, latching onto your breast, would roll up their eyes in an ecstasy that was comic in its seriousness, though your joy was no less grave,but you’re not going back to so much, and more and more, the longer you live there’s more not to go back to, and what you demand in your gratitude and greedis more life in which to get so attached to something, someone or someplace, you’re sure you’ll die right then when you can’t have it back, something you don’t even knowthe name of n