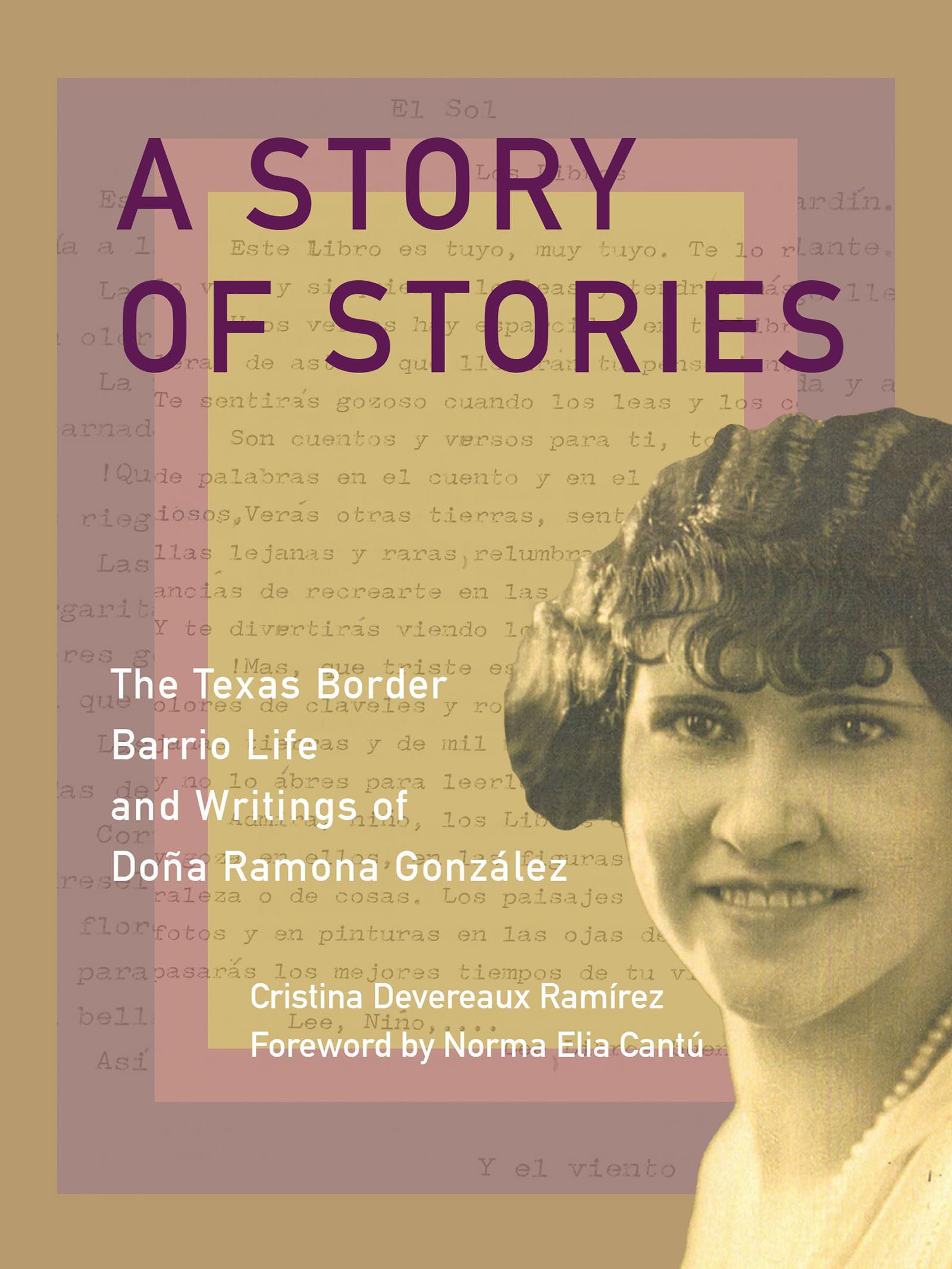

A Story of Stories: The Texas Border Barrio Life and Writings of Doña Ramona González

$10.66

by Cristina Devereaux Ramírez

Shop Now

One afternoon in fall 2015 Cristina Devereaux Ramírez’s mother called and, with a tone of urgency in her voice, asked her to come to the house and take a look at something she had discovered when she was sorting through boxes in the attic. When Ramírez arrived, she found her family sifting through papers in an old vegetable box, reading some of the more than 750 pages of Spanish language poems, short stories, fables, and dichos Ramírez’s maternal grandmother, Ramona González, had written. Some pieces were works in progress, complete with word and phrase strikethroughs and handwritten notes in the margins, while others were neatly typed prose or what might have been final drafts. None of González’s writings had seen the outside of that box for decades, at least since 1995 when the family matriarch passed away. González—or Doña Ramona, as she was often called—was born in 1906 in the El Paso border barrio of Chihuahuita, sometimes referred to as the Ellis Island of the Southwest. Her writing celebrates the rich Mexican American culture of Chihuahuita, a neighborhood the National Trust for Historic Preservation identified in 2016 as one of America’s most endangered historic places. A mother, corner grocery store owner, published writer, and community activist, González was one of the few Tejanas profiled in Worthy Mothers of Texas, 1776–1976 A Story of Stories from a Texas Border Barrio , Ramírez chronicles the life of her abuela with the care of a granddaughter and, with the eye of a scholar, analyzes selections from González’s work and its significance to El Paso history, Chicano literature, border barrio folklore, and cross-border civic movements in the mid-twentieth century. Cristina Devereaux Ramírez is an associate professor of English and director of the rhetoric, composition, and the teaching of English graduate program at the University of Arizona. She is the author of Occupying Our Space: The Mestiza Rhetorics of Mexican Women Journalists and Activists, 1887–1942 , which won the 2016 Winifred Bryan Horner Outstanding Book Prize, and the coeditor, with Jessica Enoch, of Mestiza Rhetorics: An Anthology of Mexicana Activism in the Spanish Language Press, 1875–1922 . She lives in Tucson. Norma E. Cantú is a Chicana scholar, fiction and nonfiction writer, and poet focused on the feminist, ethnographic stories of the U.S.-Mexico border. She is the author or editor of six books, including Cabañuelas , and the recipient of numerous awards. She is the Norine R. and Frank T. Murchison Distinguished Professor of the Humanities at Trinity University and lives in San Antonio, Texas. In 1991 as a young college student, I moved in with my eighty-five-year-old grandmother, Doña Ramona, to attend The University of Texas at El Paso. In doing so, I followed the traditional Mexican custom of the younger generation caring for their elders. I took the small single room in the back of a duplex apartment in an old barrio with El Paso High School visible from the front step. Nothing fancy. During my college years, I never lived in the dorms or moved in with friends, nor wanted to. And I don’t believe that I missed anything. On the contrary, my life was all the richer for the time spent with my Doña Ramona. For five years, my grandmother and I ate, slept, and lived in close communion. Closing my eyes, I can see her sitting quietly in the sun-drenched morning nook of her dining table. Her figure, hunched over the edge of the table, cast a shadow over her breakfast: café con pan. Other times, she would lean into a card game of solitaire she incessantly played. I felt what many young kids might feel toward their grandparents?a mixture of deep love cloaked in a curiosity of their life and how they lived. I wondered, what would it have been like to live through the Great Depression? To live through the struggles of the first and second world wars? Living in an age of emerging technologies that she didn’t, or even want to understand, Doña Ramona came from what seemed a different world. This otherworldliness drew people to her. On many occasions, my grandmother and I sat in silence while I ate, and she played solitaire. Other times we talked. Between us, the cross-border language in personal and daily pláticas sustained our relationship. Central to Mexican culture and family life, pláticas or talks center around knowledge exchange. While eating lunch one afternoon, she pointed to the typewriter that sat covered on the cluttered desk in the dining room. In a calm, yet almost melancholy voice, she said, “Cuando era mucho más joven, me encantaba escribir.” Leaning in to reach the desk drawer, she pulled out a thin literary journal with a brown cover. She opened it and showed me her name in the table of contents. She set it on the table as if to entice me to read her words and then went back to playing solitaire. In silence, I browsed the contents of the yellowing paper journal titled Chicanas en la literatura y