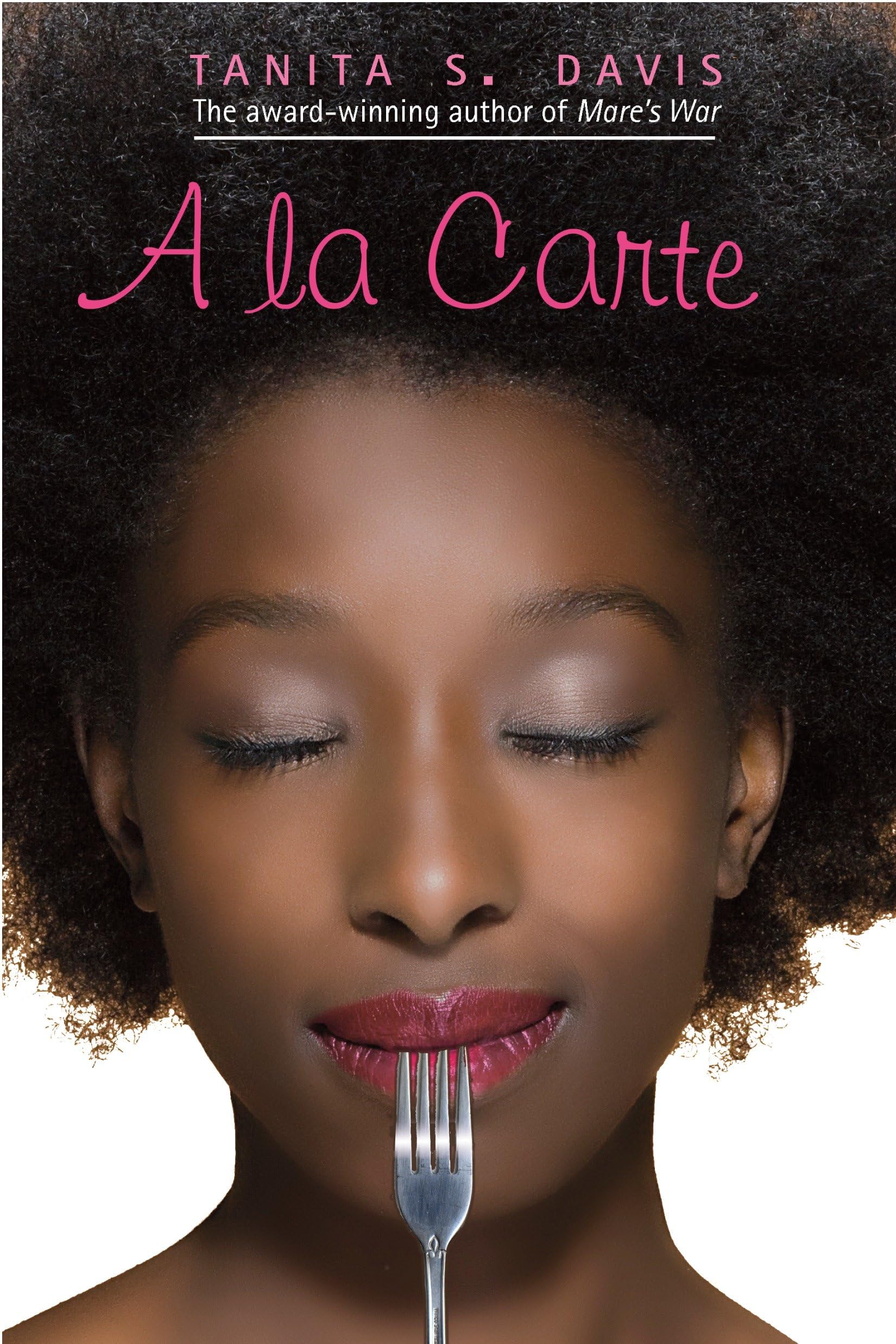

SEVENTEEN-YEAR-OLD LAINEY DREAMS of becoming a world famous chef one day and maybe even having her own cooking show. (Do you know how many African American female chefs there aren’t ? And how many vegetarian chefs have their own shows? The field is wide open for stardom!) But when her best friend—and secret crush—suddenly leaves town, Lainey finds herself alone in the kitchen. With a little help from Saint Julia (Child, of course), Lainey finds solace in her cooking as she comes to terms with the past and begins a new recipe for the future. Peppered with recipes from Lainey’s notebooks, this delicious debut novel finishes the same way one feels finishing a good meal—satiated, content, and hopeful. “Davis’s debut offering is as delightful and fulfilling as the handwritten recipes in progress included at the end of each chapter.”— Kirkus Reviews "A book with a lot of heart. Readers will relate to Lainey, who doesn't always say the right thing, who has a love-hate relationship with her mother, and who finds her dreams realized at the novel's end." —School Library Journal "Davis's first novel shows much promise for good things to come. Too few novels feature well-drawn, well-educated, middle-class African American characters like Lainey and her family." —Booklist This is Tanita S. Davis’s first novel. She made her first pâte à choux in high school, discovered that Mae Ploy sauce goes with almost everything, and that there’s nothing on earth like good Thai food. She lives in Northern California with two finches, a snake named Willful, and the world’s best baker. 1 An empty plate hits the stainless steel deck in the kitchen of La Salle Rouge with a clatter. “Order up!” somebody shouts from behind me, and the noise level in the kitchen climbs for a moment as sous-chefs and kitchen assistants step and turn in their quick-paced dance. Servers carrying plates to the dining room weave expertly in among the bussers wheeling trays of dirty dishes away. Along the prep counters, white-coated chefs bend to apply finishing touches to warm plates—a curl of deep green parsley, a swirl of roasted pepper coulis, a scattering of white peppercorns. La Salle Rouge has a reputation for excellent meals. “Order up!” “Let’s move it, people!” Even though she’s yelling at the top of her lungs, our executive chef, Pia Sambath, is in a good mood. I can tell, because none of the line cooks look like they’re trying to hide in their collars. Sometimes, when there’s a major rush on, the yelling turns into screaming and an awful silent concentration. It’s not a good time to be in the kitchen then. “Order up, table six!” A red-jacketed server with a pepper grinder under his left arm hustles past with two orders of a creamy soup in white bisque bowls, the steam rising from them making my mouth water. I watch him pass through the chaotic kitchen, imagining him gliding into the dining room, where the walls are a rich, deep red, the floor is old polished hardwood, and the lighting is subdued candlelight in silver sconces on the walls. Maybe the server slides the soup onto a table for two in front of the long, narrow windows that look out onto the courtyard fountains. Maybe he takes the bowls upstairs to the rooftop seating and offers pepper to a young couple who are there to get engaged. It’s happened before. La Salle Rouge is just the type of restaurant where people go to propose or mark fiftieth anniversaries with fancy entrees and rich desserts. From my stool in the back corner of the room, I watch clouds of steam rise to the high ceilings from the metal sinks under the window. Smoky fragrances from a heavy cast-iron grill sizzling on a gas range mingle with the pungent smell of garlic and onions and the deeper tones of coffee. The silvery crash of forks and knives hitting the heavy rubber sanitizer trays almost drowns out my mother’s voice calling me over the cacophony. “Lainey? Lai-ney! Elaine Seifert!” Sighing, I look up to see my mother standing at the far end of the kitchen, wrapped in a huge apron and wrist-deep in some kind of dough. Her close-cropped black curls are covered by a toque blanche, the white chef’s hat, and her deep brown skin shows a contrast- ing smudge of white flour on the cheek, just below her dimple. “Homework?” My mother mouths the word exaggeratedly, eyebrows raised, and I roll my eyes. Frowning, she points with her chin to the side door that leads to the stairs. I roll my eyes again, mouthing, Okay, okay, not needing her to pantomime further what she wants me to do. I hate the thought of leaving the clattering nerve center of the restaurant to wrestle with my trigonometry homework in my mother’s quiet office downstairs. “Order!” The bright lights and swirl of noise and motion are muffled as the kitchen door swings closed behind me. It’s hard to remember a time when the restaurant hasn’t been the center of our lives. Mom used to be a copy editor and wrote food features for our local paper, the Cla