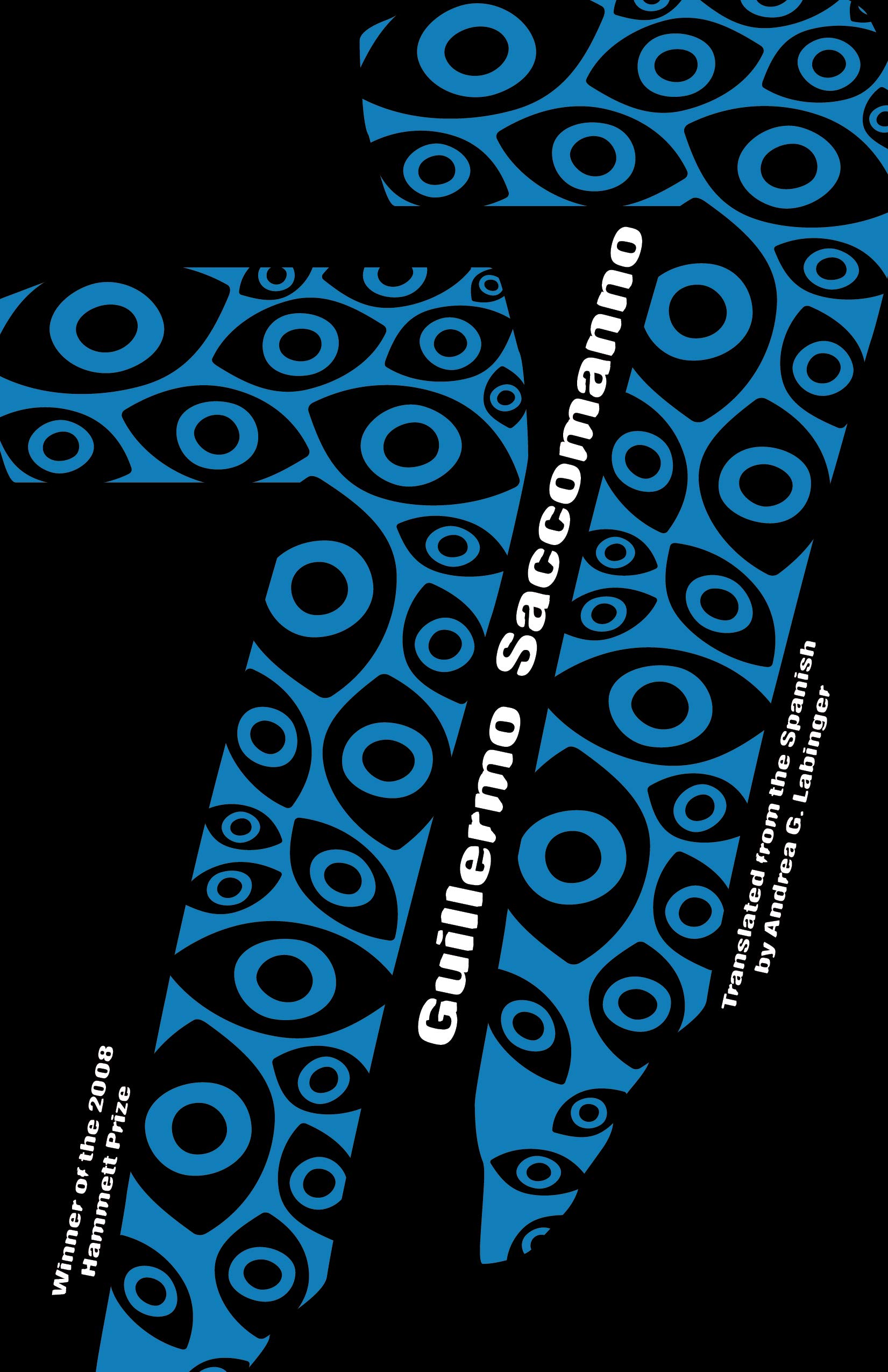

Buenos Aires, 1977. In the darkest days of the Videla dictatorship, Gómez, a gay high-school literature teacher, tries to keep a low profile as one-by-one, his friends and students begin to disappear. When Esteban, one of Gómez’s favorite students, is taken away in a classroom raid, Gómez realizes that no one is safe anymore, and that asking too many questions can have lethal consequences. His life gradually becomes a paranoid, insomniac nightmare that not even his nightly forays into bars and bathhouses in search of anonymous sex can relieve. Things get even more complicated when he takes in two dissidents, putting his life at risk—especially since he’s been having an affair with a homophobic, sadistic cop with ties to the military government. Told mostly in flashbacks thirty years later, 77 is rich in descriptive detail, dream sequences, and even elements of the occult, which build into a haunting novel about absence and the clash between morality and survival when living under a dictatorship. Winner of the 2008 Hammett Award " 77 is a taut historical thriller with noir overtones. . . . As his characters grapple with love, allegiance, and daily life under a dictatorship, every action is a form of resistance." — Foreword Reviews " 77 sings a dark song of one man’s struggle to stay human when the inhumane lurks on every corner and the day-to-day reality of his world is curdled by the struggle between unchecked power and subversive acts." —Ross Nervig, Southwest Review "A great novel. . . . I am―as we all should be―grateful for 77 and all novels like it." —Patrick Nathan, Full Stop "Like Twin Peaks reimagined by Roberto Bolaño, Gesell Dome is a teeming microcosm in which voices combine into a rich, engrossing symphony of human depravity." — Publishers Weekly In prickly, energized language, Saccomanno . . . captures the fearfulness of those living under dictatorship." — Library Journal "Cynical and funny: a yarn worthy of a place alongside Cortázar and Donoso." — Kirkus Reviews "By using a narrator who is not shocked, who does not look away from anything, Saccomanno shines a gruesome, graphic light on what people are willing to ignore so that their comfort remains intact.” —Kim Fay, Los Angeles Review of Books "77 is ostensibly a novel about Argentina’s Dirty War; it is also a book about reconciling inaction with survival." — World Literature Today “77 is, among other things, a potent reminder of the gruesome paths of totalitarian dictators.” —Lew Whittington, New York Journal of Books "A choral, savage, and ruthless work, considered to be the great Argentine social novel." — Europa Press Guillermo Saccomanno is the author of numerous novels and story collections, including El buen dolor , winner of the Premio Nacional de Literatura, and 77 and Gesell Dome , both of which won the Dashiell Hammett Prize. (Both available from Open Letter.) He also received Seix Barral's Premio Biblioteca Breve de Novela for El oficinista and the Rodolfo Walsh Prize for nonfiction for Un maestro . Critics tend to compare his works to those of Balzac, Zola, Dos Passos, and Faulkner. Andrea G. Labinger is the translator of more than a dozen works from the Spanish, including books by Ana María Shua, Liliana Heker, Luisa Valenzuela, and Alicia Steimberg, among others. (From the beginning.) The way I tell this story may be terrifying, Professor Gómez begins. And he adds: How can you narrate terror. But I won’t back down, he says. Even if people criticize my story and the thoughts it provokes, I won’t back down. As Martín Fierro says, “I sing what I think, which is my way of singing.” I know my story makes me sound like a gaucho singer on the run. Because anyone who tells it straight will always be a gaucho singer on the run. Attention, demands the professor. When a song is popular with the powerful, it can’t be trusted. People sing it for convenience’s sake. They say fear’s no fool. And what about terror. Terror makes a person more cunning. Not more intelligent, more cunning. Like a fox that eludes the hunting party. But that survival skill, when it’s honed, becomes madness. Terror, that’s what I’m going to talk about. I’ll say it again: my story’s not likely to amuse, because for me there’s no joy in telling it. In more than one way, this could be the story of an act of submission. Some might say it’s brave to confess to an act of submission, but it’s better not to commit it in the first place. And yet, if my story strikes anyone as funny, the humor probably has its merit: terror and laughter are incestuous siblings. The fact that it seems to take on a bolder tone now, perhaps more like a confession than a tale to be told, doesn’t redeem me. I’m an old man who repeats himself. I’m over eighty. And I have nothing to lose anymore except my papers. But papers, like words, blow away in the wind. The professor adjusts his glasses and observes the overloaded, sagging shelves of his library, the double row of bo