ANNE ARUNDEL: The Hidden Matron of a Catholic Colony: Gender, Silence, and the Domestic Foundations of Maryland (Chesapeake Unwritten)

$19.99

by Bill Johns

Shop Now

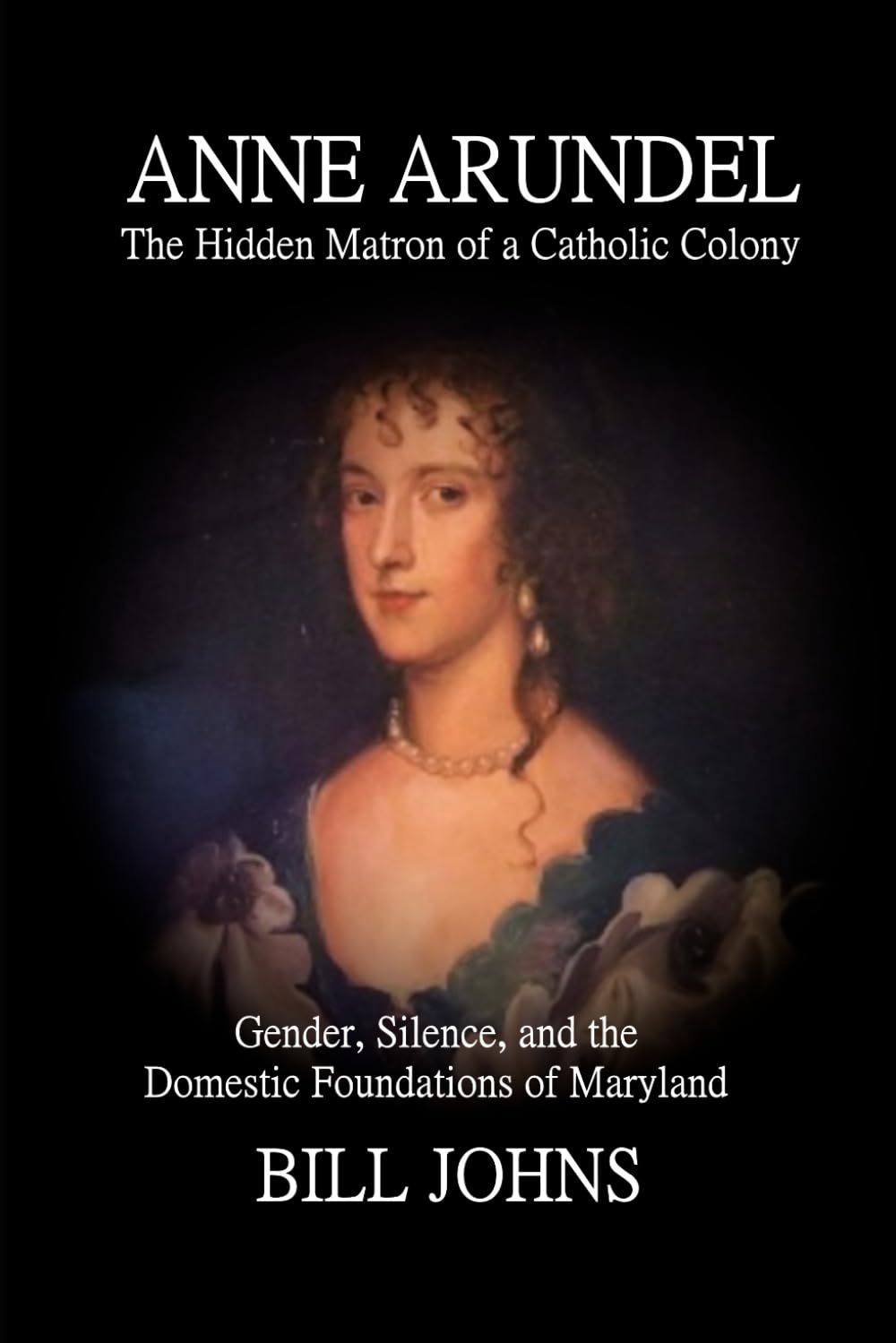

Anne Arundel: The Hidden Matron of a Catholic Colony is a haunting excavation of historical silence, one that asks how a woman can be remembered so visibly and yet remain so profoundly unknown. A work of historical nonfiction grounded in cultural history, gender studies, and the memory politics of early colonial America, this book uncovers the life—and disappearance—of Anne Arundel, the English noblewoman whose name adorns one of Maryland’s most populous counties but whose biography is almost entirely missing from public record. For readers of literary history, women’s studies, and colonial America, this is a revelation: not just of one woman’s story, but of how history itself is structured to forget her. Drawing from the archival shadows of recusant England and early proprietary Maryland, Anne Arundel traces the life of a woman born into one of England’s oldest Catholic families—houses of ritual and secrecy that survived the Protestant Reformation not through rebellion, but through practiced discretion. Anne Arundell of Wardour Castle married Cecilius Calvert, the Second Lord Baltimore, and bore his children in a London household that functioned as a spiritual stronghold for the English Catholic underground. She never traveled to Maryland. She died in 1649 at the age of thirty-four. One year later, the province’s fledgling colonial assembly renamed a jurisdiction in her honor: Anne Arundel County. There is no record she asked for it. No indication that her husband directed it. Her name was chosen not to commemorate her deeds, but to domesticate the political instability of a colony veering toward Protestant control. Through elegant, incisive chapters, this book reconstructs Anne’s world from the margins of record: the quiet discipline of the recusant household, the moral authority wielded by women within spaces of architectural faith, and the inheritance of governance transmitted through maternal formation rather than state decree. But it also traces how Anne’s name became a symbolic possession—used by colonial men to stabilize power, signal Catholic legitimacy, and invoke noble lineage at a moment of profound political uncertainty. In death, Anne became a matron in name only, invoked not for who she was but for what her absence allowed others to claim. The narrative confronts the long afterlife of that substitution. In the centuries that followed, Anne Arundel’s name was embedded into the bureaucratic fabric of Maryland. She is invoked daily—in police departments, school systems, zoning boards, and property deeds—but rarely known. The county bears her name, yet offers no monument, no grave, no verified portrait. What survives is administrative omnipresence without personal memory. Even the image most often attributed to her—a pale young woman in seventeenth-century attire—is of dubious provenance. Still, it circulates widely, not because it is accurate, but because it is plausible. Because the county needs a matron, and in the absence of biography, fiction will do. Anne Arundel was not forgotten. She was structured into absence—used as a symbolic gesture precisely because she could no longer speak. Her name softened the political violence of empire by wrapping it in the image of maternal dignity. And it illustrated a broader colonial habit: to name land for women whose biographies could be flattened into virtue, silence, or grace, without ever needing to account for their lives. For readers drawn to the Chesapeake, to early Maryland, or to the untold stories that lie just beneath the surface of the map, this is an essential act of historical recovery. The question is not only who Anne Arundel was—but why we never thought to ask. Let the county be a starting point. Let the name on the sign lead inward. There is a matron beneath the charter, but she is made of silence. What we choose to remember now speaks to what we’ve long accepted to forget.