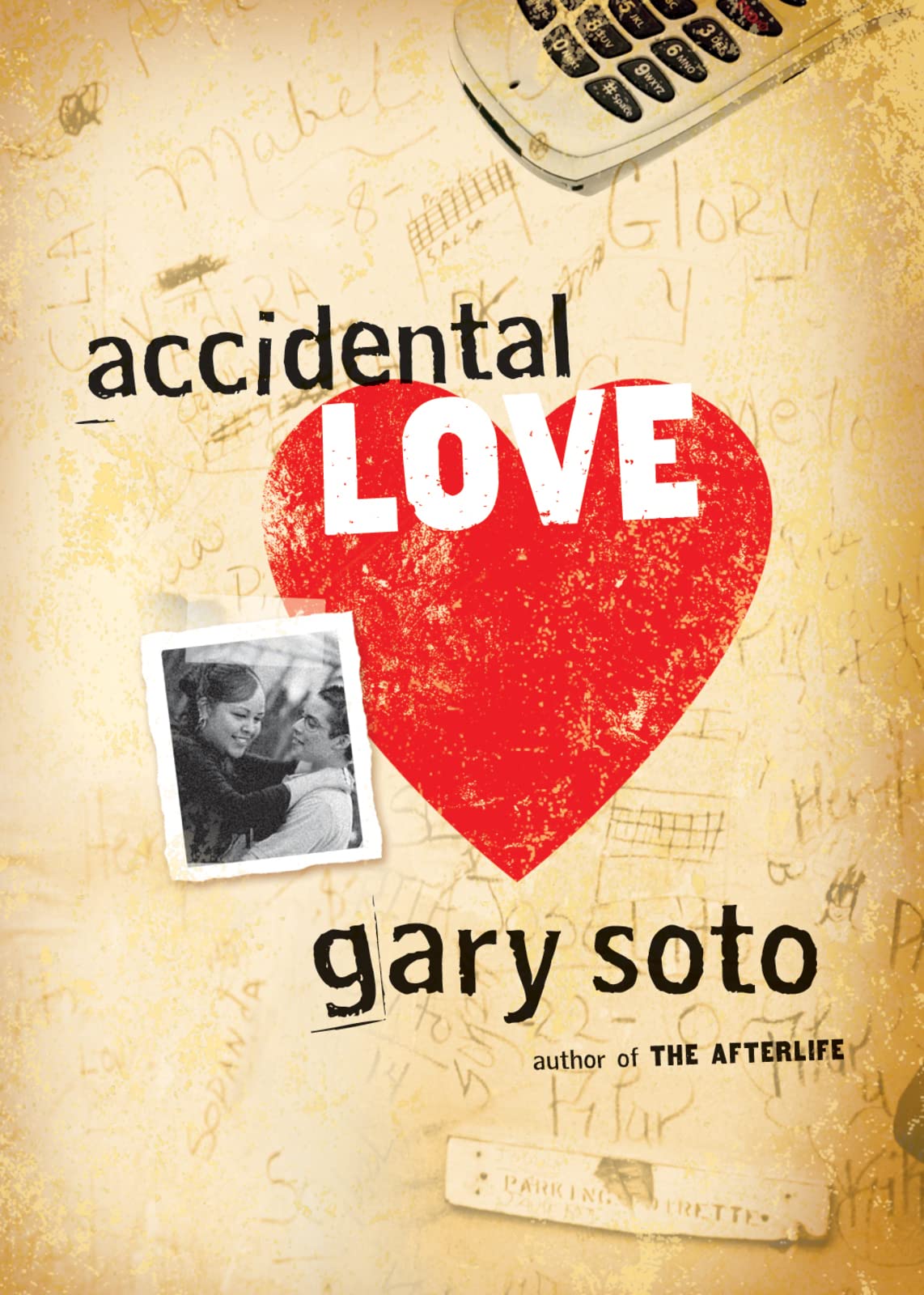

It all starts when Marisa picks up the wrong cell phone. When she returns it to Rene, she feels curiously drawn to him. But Marisa and Rene aren't exactly a match made in heaven. For one thing, Marisa is a chola ; she's a lot of girl, and she's not ashamed of it. Skinny Rene gangles like a sackful of elbows and wears a calculator on his belt. In other words, he's a geek. So why can't Marisa stay away from him? Includes a glossary of Spanish words and phrases. "The tough-girl/good-guy romance is a refreshing twist, and Marisa and Rene are unique and long-overdue characters."-- The Bulletin "With humor and insight, [Soto] creates memorable, likable characters."-- Booklist Gary Soto 's first book for young readers, Baseball in April and Other Stories, won the California Library Association's Beatty Award and was named an ALA Best Book for Young Adults. He has since published many novels, short stories, plays, and poetry collections for adults and young people. He lives in Berkeley, California. Visit his website at garysoto.com. At fourteen Marisa welcomed any excuse to miss school. But today she had a good reason for cutting class. Alicia, her best friend, lay in the hospital with a broken leg and a broken heart, all because her boyfriend had crashed his parents' car when a tire blew. The leg had broken in the crash, but her heart had broken when the glove compartment opened on impact and shot out a photo of stupid Roberto with his arm around another girl. Marisa was off to give her homegirl a meaningful hug. "He's such a shisty rat," she growled as she pictured that no-good Roberto, an average-looking fool whose fingers were always orange from Cheetos. She, too, savored that junk food snack, but-she argued-at least she always licked her fingers clean. But not him! Stupid jerk! Big pendejo! How could Alicia stand his face? She was always treating him to food and paying for gas for their car rides into the country. Marisa's anger was deflected to a passing station wagon that nearly hit her as she started across the street. "You estúpido!" she spat as she threw her hands into the air in anger. The pair of eyes she saw in the rearview mirror were old and could have belonged to any of her six aunts. Ay, Chihuahua, how Marisa's grandmother bore children, all female, all large, all different as pepper from salt. Marisa admonished herself for yelling at the elderly driver. "Maybe it was one of mis tías," she told herself, and her rage dissolved. Her thoughts returned to Alicia tucked away in a hospital bed and then quickly to Roberto, the rat. If my boyfriend was cheating on me . . . She was brooding when she remembered that she didn't have a boyfriend. So what was the worry? She found herself shrugging and thinking she'd never have a boyfriend as she peeked at her stomach with its roll of fat. "Room 438," she told herself as the salmon-colored hospital came into view. "That's where my homegirl is. She's gonna be hecka surprised." Marisa swallowed her fear. Hospitals were where you went to die. She remembered Grandma Olga's last days. Her grandmother, struggling with cancer, rolled from her side to her stomach to sitting on the bed and dangling her rope-thin legs. Dying, Marisa had thought then, was a matter of getting comfortable. Marisa rode up in an elevator between two male nurses with paper bootees on their shoes. She herself had considered becoming a nurse, but that was years before, when she had dolls whose arms would fall off, and she would stick the arms back on only to have them fall off again. The dolls, she remembered, lay under her bed, their eyes open but not taking in a whole lot. The elevator opened with a sigh. Marisa stepped out, glancing slowly left and then right. "Room 438," she muttered as she cut a glance to a man in a wheelchair pushing himself up the hallway by the strength of his thin arms. A bottle of clear fluid hung on a steel pole behind him, and clear tubes were delivering that fluid into his arms. Marisa grimaced. She would hate to have something stabbed in her all day. Does it hurt like a pinch? she wondered. A bee sting? When she located the room, Alicia was staring gloomily toward the ceiling. For a moment Marisa figured that Alicia was appealing to God in heaven. But as she stepped inside, she realized that Alicia's eyes were raised to a muted television. On the screen some carpenter was carrying a sheet of plywood over his head. It was a boring home-decorating show, the kind her mother liked to watch on Saturday afternoons. "Hey, girl!" Marisa greeted loudly. Alicia lowered her eyes to her friend, and for a few seconds her face was expressionless. Then it slowly blossomed with a smile. Her eyes narrowed into little slits of light. "Marisa," Alicia greeted in return. She raised a feeble hand and Marisa grasped her friend's hand and gave it a loving squeeze, then smothered Alicia with a hug. "How's it? Your pata?" Marisa asked as she sat on the edge of