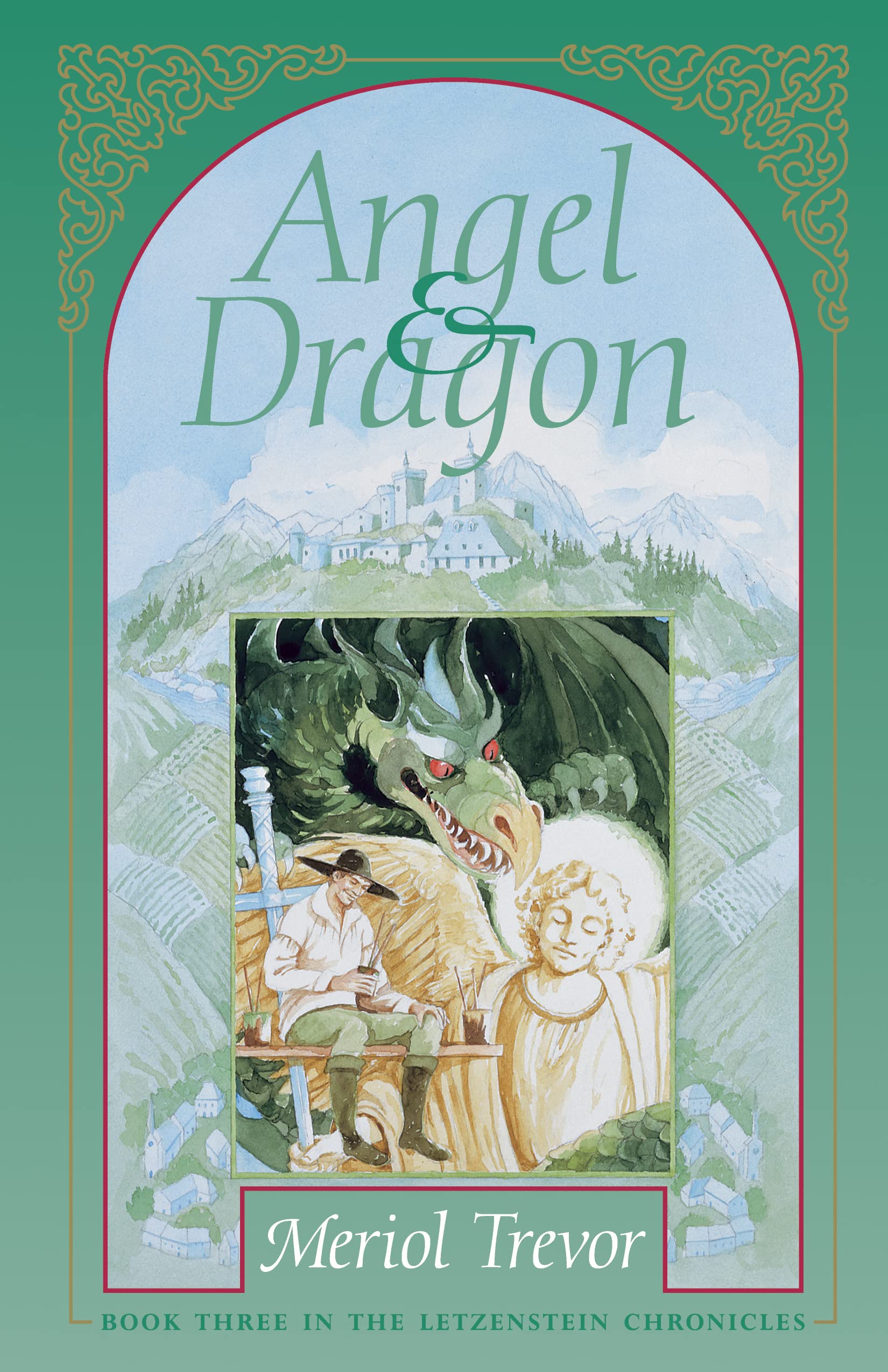

The adventures of Rafael le Marre and his friends continue in this third book of the Letzenstein Chronicles. Catherine Ayre and her cousin Giles come to Letzenstein in the summer of 1849. Raf is settled in Xandeln with a crowd of orphans—but Giles, at least, is not impressed with his unconventional ways. After a terrorist bombing in which the Grand Duke is thought to be killed, Julius Varenshalt tries to take political control. Catherine, and even Giles, fear for Raf's life—and indeed it has never more precariously hung in the balance. Europe, 1849 RL5 Of read-aloud interest ages 9-up Meriol Trevor (1919-2000) graduated from Oxford in 1942. Her first publications were books for children and historical novels. Miss Trevor said, “In all my books for children I have concentrated on personal relations, usually with the more serious confrontations between the adults—but also adult/child and child with child—occasioned by the general events going on at the time.” This emphasis on relationship is a key feature in all of her books. Miss Trevor also wrote a number of acclaimed biographies—including ones on Pope St. John XXIII, St. Philip Neri and St. John Henry Newman. In 1967 she was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature. GILES AND CATHERINE sat at one of the little tables outside a café in Trier, drinking lemonade. Afternoon was drawing towards evening but the August sun was still warm and after hours spent looking at old churches and ancient Roman walls they were quite glad to sit still and wait for Giles’s father to return from calling on a friend. Giles Hawthorne and Catherine Ayre were cousins and they were both fourteen, but they did not know each other well. Sir Walter Hawthorne, having spent some time in Brussels on a diplomatic mission, was now taking a holiday, travelling first to Aachen and Cologne on the Rhine and then visiting Trier, which was on the Moselle. “I like Trèves,” said Giles, giving the town its French name. “It makes Caesar come alive to think that this was where the Treveri tribe lived, when he was conquering Gaul.” “I like it too,” said Catherine, “but I wish we could go on to Letzenstein soon.” Letzenstein, a small independent state between France and Germany, was just across the river, westward. “Nothing historically important has ever happened in Letzenstein,” said Giles. “I can’t think why you are so keen on it, considering that last year you seem to have spent most of your time running away from revolutionaries.” Catherine, who looked so quiet and shy, happened to be the daughter of a princess of Letzenstein who had made a runaway marriage with an English officer. She could not remember her parents, who had died in India, leaving her to the care of an old great-aunt in Kent. Until she was thirteen she had not been in her mother’s country, but then she had been summoned by her formidable grandfather, the old Grand Duke Edmond Waldemar, and had found herself a pawn in the political power game there. “It’s not just the place, it’s the people I like,” she said. “My uncle Constant and his cousins—except Julius. I didn’t like him at all.” Giles had heard how the Grand Duke had disinherited his son Constant and had tried to make his nephew Julius Varenshalt the Regent for Catherine, on his deathbed. In spite of this, Constant had succeeded to the title, to the satisfaction of the people and to Catherine’s relief. Because Catherine said she did not like Julius, Giles instantly decided that he was probably the only sensible member of Catherine’s foreign family. “I daresay the old Grand Duke knew who would make a good ruler and who would not,” he said. “Your foreign uncle sounds a muddler to me.” He always called them “your foreign uncle” and “your foreign cousins” and this annoyed Catherine, who felt more at home with them than with her English relations. She did not know Giles well because it was not till her great-aunt had died, last spring, that she had gone to live with the Hawthornes in their big London house. Aunt Eleanor was her father’s sister. Giles was at Eton and often went away in the holidays to stay with friends. He had two grown-up married sisters, but he was the only son. Although he was a month or two younger than Catherine, he was taller than she was, a self-confident, active, intelligent boy, brown-haired and grey-eyed, and, it seemed to Catherine, determined to know better than herself about everything. Catherine was shy, rather thin, with straight brown hair and ordinary brown eyes; her eyebrows lifted at the ends: it was her only noticeable feature. But under her quietness were strong feelings, which she had first become aware of that time in Letzenstein in January 1848. In April that year she had expected to go back for her uncle Constant’s wedding, but her great-aunt’s death had prevented it. Afterwards there were so many revolutions in Europe that Sir Walter Hawthorne would not allow her to go abroad. This year there were revolutions in Italy but