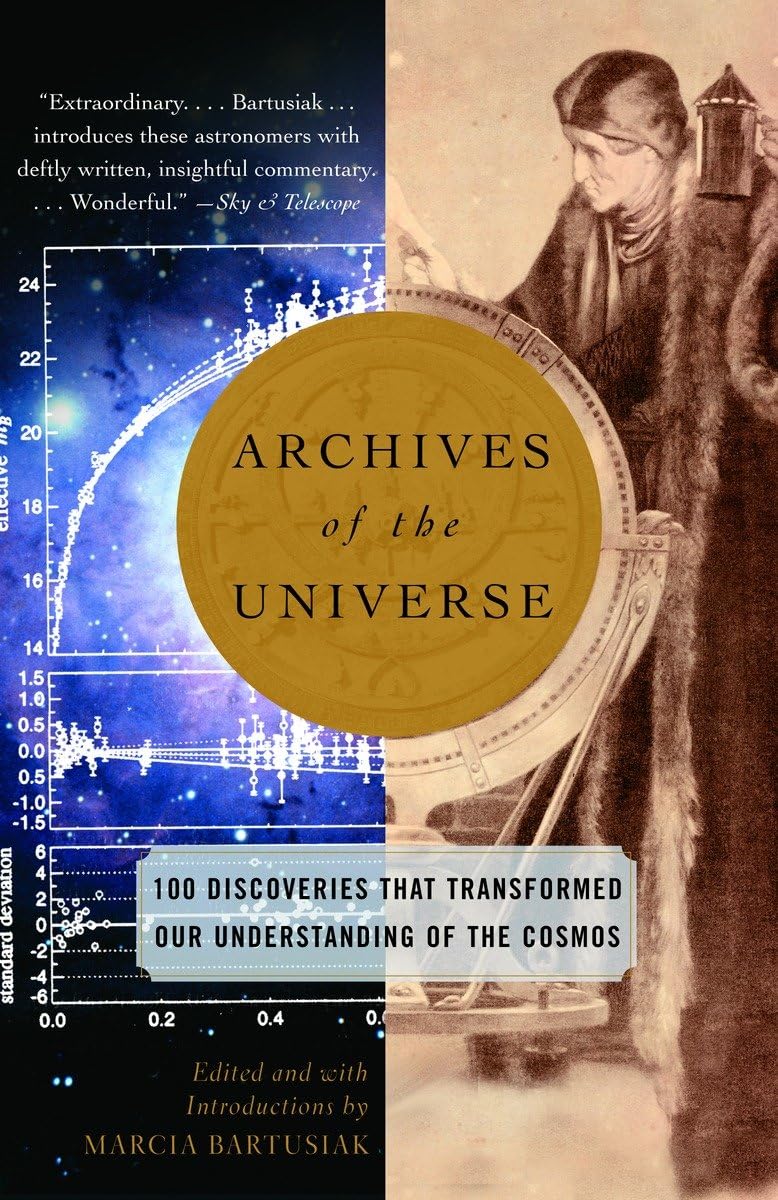

Archives of the Universe: 100 Discoveries That Transformed Our Understanding of the Cosmos

$17.02

by Marcia Bartusiak

Shop Now

An unparalleled history of astronomy presented in the words of the scientists who made the discoveries. Here are the writings of Copernicus, Galileo, Kepler, Newton, Halley, Hubble, and Einstein, as well as that of dozens of others who have significantly contributed to our picture of the universe. From Aristotle's proof that the Earth is round to the 1998 paper that posited an accelerating universe, this book contains 100 entries spanning the history of astronomy. Award-winning science writer Marcia Bartusiak provides enormously entertaining introductions, putting the material in context and explaining its place in the literature. Archives of the Universe is essential reading for professional astronomers, science history buffs, and backyard stargazers alike. "Extraordinary. . . . A rich archaeological dig. . . . Bartusiak . . .introduces these astronomers with deftly written, insightful commentary. . . . [A] wonderful book." — Sky & Telescope "[Bartusiak] provides a helpful road map with her lucid explanatory essays and annotation." — The New York Times "Bartusiak has done astronomy a great favor." — New Scientist "The reader gets not only a clear and concise history of astronomy . . . in Bartusiak's fine introductions . . . but also excerpts from many of the memorable papers written by the scientists who made the pivotal astronomical discoveries." — Scientific American An unparalleled history of astronomy told through 100 primary documents--from the Maya's first recorded efforts to predict the cycles of Venus to the 1998 paper that posited an accelerating universe. Award-winning science writer Marcia Bartusiak is a wonderfully compelling guide in this sweeping overview. Her authoritative, accessible commentaries on each document provide historical context and underscore the more intriguing and revolutionary aspects of the discoveries. Here are records of the earliest naked-eye celestial observations and cosmic mappings; the discovery of planets; the first attempts to measure the speed of light and the distance of stars; the classification of stars; the introduction of radio and x-ray astronomy; the discovery of black holes, quasars, dark matter, the Big Bang, and much more. Here is the work of Copernicus, Galileo, Kepler, Newton, Halley, Hubble, and Einstein, as well as that of dozens of lesser-known scientists who have significantly contributed to our picture of the universe. An enthralling, comprehensive history that spans more than two millennia--this is essential reading for professional astronomers, science history buffs, and backyard stargazers alike. "From the Hardcover edition. Marcia Bartusiak is the author of Thursday’s Universe , Through a Universe Darkly , and Einstein’s Unfinished Symphony . Her work has appeared in many magazines, including Astronomy , National Geographic , Discover , Science , and Smithsonian . A two-time winner of the American Institute of Physics Science Writing Award, she teaches in the graduate program in science writing at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and lives in Sudbury, Massachusetts, with her husband. The Ancient Sky The fortuitous alliance of two agents led to the birth of astronomy: curiosity and necessity. From savannas, mountaintops, and forest clearings, the first celestial observers looked up at the nighttime sky and beheld a vast, pitch-black bowl covered with sparkling pinpoints of light. While likely awed at first by this jewel-like canopy, imagining it as a vaulted roof through which the fires of the gods flickered, prehistoric peoples eventually learned there were practical benefits to studying the sky’s incessant motions and cycles. Tracing out patterns of stars—constellations—became a useful procedure for establishing a coordinate system across the heavens, and the leisurely parade of these stellar figures over the seasons served as valuable markers for navigation, agriculture, and timekeeping. As the Greek poet Hesiod advised in the eighth century b.c., “When the Pleiades, daughters of Atlas, are rising, begin the harvest, the plowing when they set.” Here the farmer was instructed to reap winter wheat in the spring, when the Pleiades rise with the Sun, and to plant seeds in the fall, when the notable constellation sets in the west before sunrise. In ancient Egypt observers noticed that the brilliant star Sirius rose in the east right before dawn, at the very time that the Nile river experienced its annual flooding. In the high northern latitudes it was the Sun’s recurrent passage that held particular significance. As winter approaches there, the Sun’s path moves steadily southward, just as the days and nights get colder. Primitive megaliths were built to mark the pivotal moment—winter solstice—when the Sun would (to much thanksgiving) turn back and once again rise higher in the sky. Relics from the first days of civilization showcase the ancients’ intense intellectual curiosity about the nighttime sky. Inscript