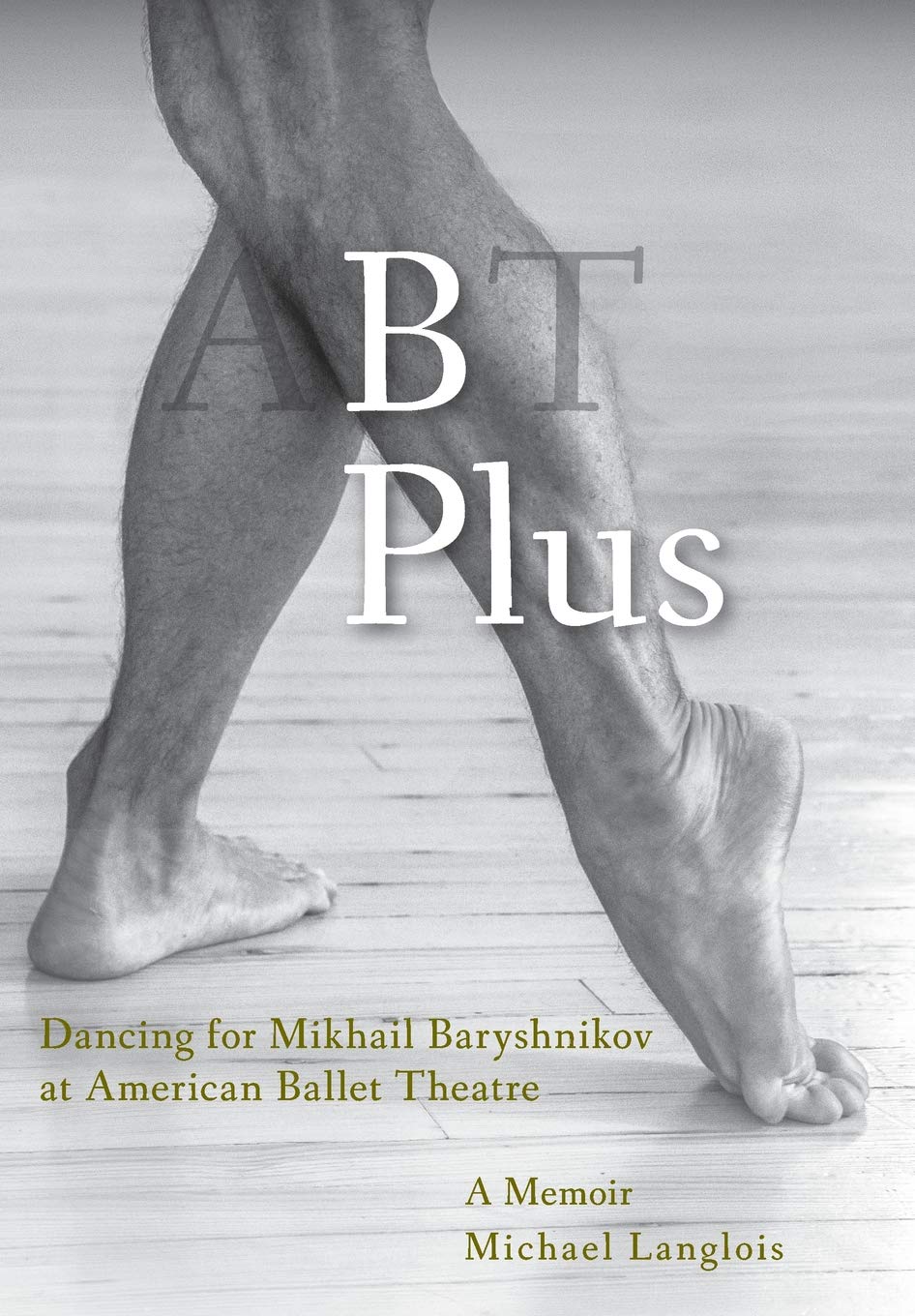

B Plus: Dancing for Mikhail Baryshnikov at American Ballet Theatre: A Memoir

$37.95

by Michael Langlois

Shop Now

Michael Langlois began studying ballet at the age of ten, convinced it would catapult him from Pop Warner directly into the NFL. Eventually forced to choose between football and ballet, he looked at his less-than-five-foot frame and decided ballet might be a more practical option. He went on to train at the North Carolina School of the Arts and the School of American Ballet in New York before being offered a job at American Ballet Theatre by the foremost dancer of the 20th century: Mikhail Baryshnikov. B Plus: Dancing for Mikhail Baryshnikov at American Ballet Theatre is an intimate look at the upper echelons of the dance world as it appeared to a young man who made it to the top of his profession only to discover a vast plateau filled with dancers whose talents and ambitions were often superior to his own. While he struggles to move beyond playing toy soldiers and happy, clueless peasants in ABT's corps de ballet, he wonders what to do about his best friend who is in love with him, how to please his world-famous boss, and just how little you have to eat in a ballet company before anyone notices you. After sixteen years as a professional, he comes to some important realizations about himself and ballet in general. "What makes ballet so intensely satisfying and beautiful to me," he writes, "is that it is so spare. There are no props. There are no instruments that have to be manipulated. It is just the dancer at that moment, and whoever they are and whatever they are capable of doing exists then and only then." KIRKUS B PLUS Dancing for Mikhail Baryshnikov at American Ballet Theatre Michael Langlois Epigraph Publishing (358 pp.) $24.95 hardcover, $18.95 paperback, $9.99 e-book ISBN: 978-1-948796-14-9; May 29, 2018 BOOK REVIEW A middling dancer reaches for heights just beyond his grasp in this wry, bittersweet memoir. Langlois, a massage therapist and writer for Ballet Review, recounts his early years as a dancer, from childhood lessons to ballet school in New York to a prized job with American Ballet Theatre, the country's premier troupe, in 1980. ABT was the fulfillment of the 19-year-old dancer's dreams, but it later became a purgatory of thwarted ambition. Langlois started in the corps de ballet, dancing minor ensemble parts around soloists and principal dancers, and he stayed there for six years while colleagues rose to starring roles. Relegated to bit parts--his one significant turn was wearing a cat costume in Cinderella, which won him positive reviews for his feline piquancy--Langlois rarely saw his name on casting lists and had little to do on tours, except in Japan, where he was mobbed by autograph-seeking schoolgirls who mistook him for an ABT principal. He worked long hours, got private coaches, and starved himself down to 135 pounds, hoping to get the superthin physique that choreographers wanted. Working against him, though, were the cursory teaching standards in the industry, which he painstakingly describes in well-observed passages on ballet training and technique. Rather than getting help and direction, he was left to sink or swim by teachers who either ignored him or tossed out baffling koans ("I turn, but I don't turn"). Yet even when he felt he'd made progress and was able to try out for better roles, he never quite made the cut. Langlois recalls disappointments with good humor but doesn't hide the pain or neuroses that plagued his career, as his mind shrank into a "narcissistic, incredibly self-critical little box." Centering his narrative is his vivid portrait of Mikhail Baryshnikov, the world's greatest dancer and ABT's artistic director, who emerges as both inspiring and maddeningly neglectful. The enigmatic "Misha" gave Langlois little feedback other than Latvian-accented asides--"Mikey, vaad you doink?"--and vague suggestions to try something different with the placement of his arms; their annual 5- or 10-minute conferences are portrayed as ordeals of fraught, uncommunicative squirming. Nonetheless, Baryshnikov's brilliant performances, which the author analyzes here in passionate appreciations, were central to Langlois' aspirations as a dancer. Pirouetting around this relationship is an entertaining ballet picaresque that's full of sharply etched thumbnails of luminaries, such as the sublimely gifted but drug-addled ballerina Gelsey Kirkland, and the straight Langlois' efforts to politely fend off gay colleagues and patrons. Threaded throughout are evocative performance scenes that marry technical detail to aesthetic impact: "out I came, stomping out the rhythm in my absurdly deep, absurdly turned-out second position as Prokofiev's music lurched forward, its odd timbre a perfect reflection of the off-kilter characters...we marched across the apron of the stage like a drunken caterpillar." The result is an absorbing saga that finds enduring value in artistic effort despite humiliations and questions