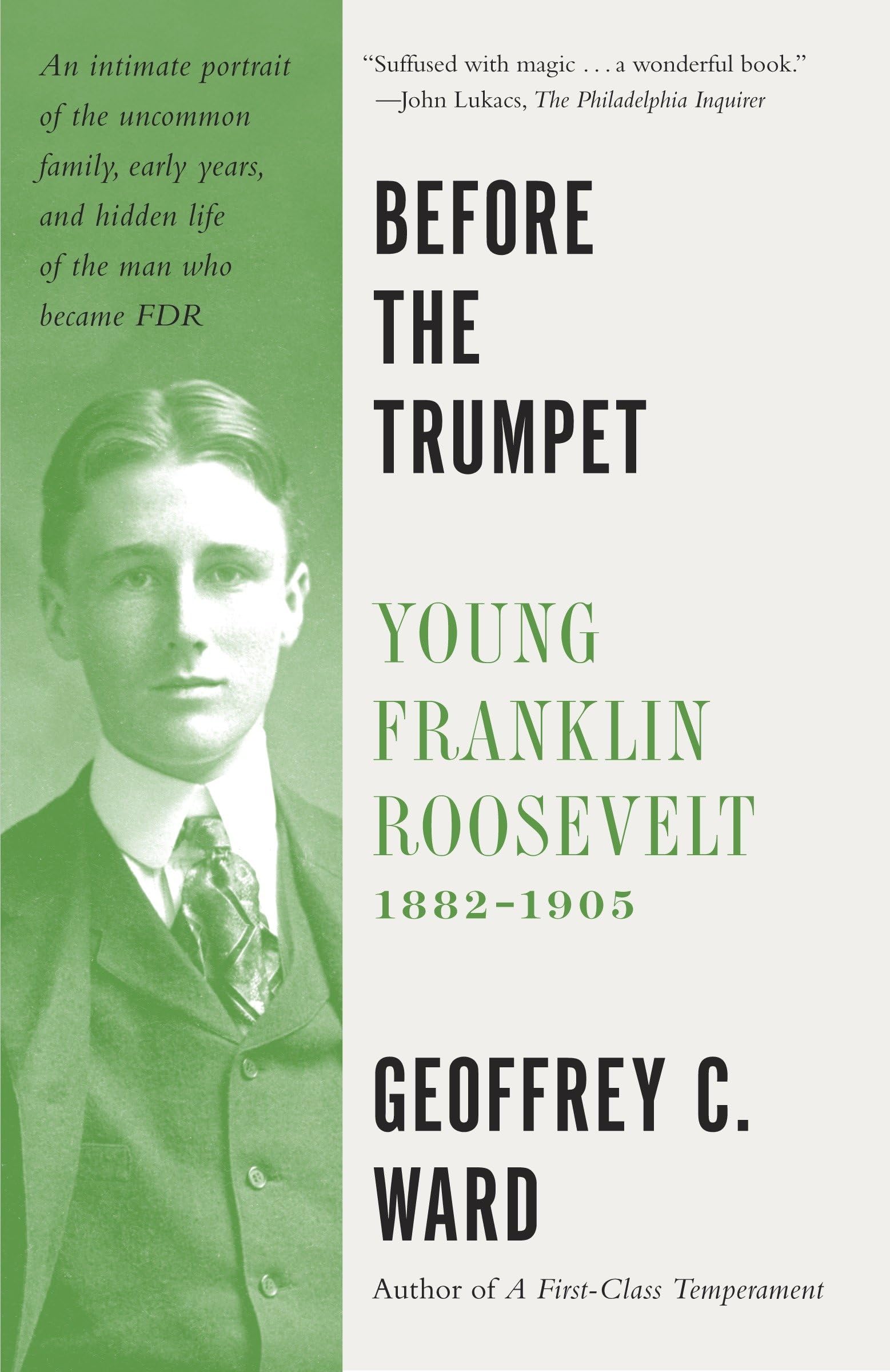

Before Pearl Harbor, before polio and his entry into politics, FDR was a handsome, pampered, but strong-willed youth, the center of a rarefied world. In Before the Trumpet, the award-winning historian Geoffrey C. Ward transports the reader to that world—Hyde Park on the Hudson and Campobello Island, Groton and Harvard and the Continent—to recreate as never before the formative years of the man who would become the 20th century’s greatest president. Here, drawn from thousands of original documents (many never previously published), is a richly-detailed, intimate biography, its central figure surrounded by a colorful cast that includes an opium smuggler and a pious headmaster; Franklin's distant cousin, Theodore and his remarkable mother, Sara; and the still-more remarkable young woman he wooed and won, his cousin Eleanor. This is a tale that would grip the reader even if its central character had not grown up to be FDR. “Suffused with magic . . . a wonderful book.” —John Lukacs, The Philadelphia Enquirer “An engrossing biography . . . Magnificent social history . . . a triumph of scholarly detective work.”— The New Yorker “The freshest and most penetrating study of the young FDR.” — Chicago Sunday Tribune “The texture is . . . richer, the detail more finely tuned than in any other portrait.” — The New York Times Book Review “Quite the best thing I have ever read about FDR and Eleanor Roosevelt. The wonder is that [it] unearths so much new and revealing material—letters, conversations, insights . . . appealing and inspiring.”— Atlanta Constitution Geoffrey C. Ward is the coauthor of The Civil War (with Ken Burns and Ric Burns), and the author of A First-Class Temperament: The Emergence of Franklin Roosevelt , which won the 1989 National Book Critics Circle Award for biography and the 1990 Francis Parkman Prize. CHAPTER ONE MR. JAMES Spring had come late to the Hudson Valley in 1867, too; and when James Roosevelt and his wife, Rebecca, drove up the long driveway to their new home on April 30 of that year, mist hid the hills beyond, and a cold, steady rain slanted down, driven by the wind off the river. The carriage splashed along the edge of a stubbled, muddy field beneath big trees, their bare limbs black and shiny with rain, and stopped in front of the house. Dark and clapboarded, it was not large as Hudson River manors went—there were just seventeen rooms—and it was in poor repair. A three-storied tower stood at the southeast comer, and a deep veranda ran the full length of the front and around one side, its pillars thickly wound with ivy. The house’s profile reminded James of a locomotive with a tall smokestack pulling a train of cars. Water dripped steadily from the overhanging eaves as the Roosevelts hurried inside. They were a handsome couple. Rebecca, then thirty-six, was a merry woman, plump and attractive, and capable of putting almost anyone at ease. Her husband was more reserved; his servants, the townspeople, even some of his friends, found it most comfortable to call him “Mr. James.” He was slender and erect, of medium height, with alert hazel eyes, a firm chin, and brown muttonchop whiskers just beginning to go gray at thirty-nine. The Roosevelts had been happily married now for fourteen years and had one child, an amiable thirteen-year-old boy named James Roosevelt Roosevelt, whom everyone including his parents called “Rosy.” At the moment he was staying with his uncle, John Aspinwall Roosevelt, at his home just two miles down the Albany Post Road, but soon he would be coming to live in the new house as well. Like many of their friends, the Roosevelts led a serene but peripatetic life, dividing the year between their country home on the Hudson, a house in New York City in which they spent the harshest winter months, and long vacations abroad. They had been at Interlaken in the Swiss Alps in September of 1865, when word came that their old house in the country, Mount Hope, had been burned to the ground. James Roosevelt’s grandfather had built Mount Hope; James himself had been born there, and he had inherited it at his grandfather’s death. Its loss had seemed “a fearful dream,” he wrote; he could not believe that his “dear old home is among the things of the past.” Rather than rebuild, James had sold the land to the State of New York for $45,000—it became the site of the Hudson River State Hospital, a mental institution—and began looking for a place of his own to buy with the proceeds. The house whose gloomy, vacant interior he and Rebecca were now exploring had not been their first choice. They had hoped to buy Ferncliffe, the far more opulent Hudson River estate of John Jacob Astor III at Rhinebeck. James Roosevelt was himself a wealthy man—general manager of the Cumberland and Pennsylvania Railroad, director of the Consolidated Coal Company of Maryland, responsible custodian of a considerable inheritance—but his fortune was inconsequential compared to th