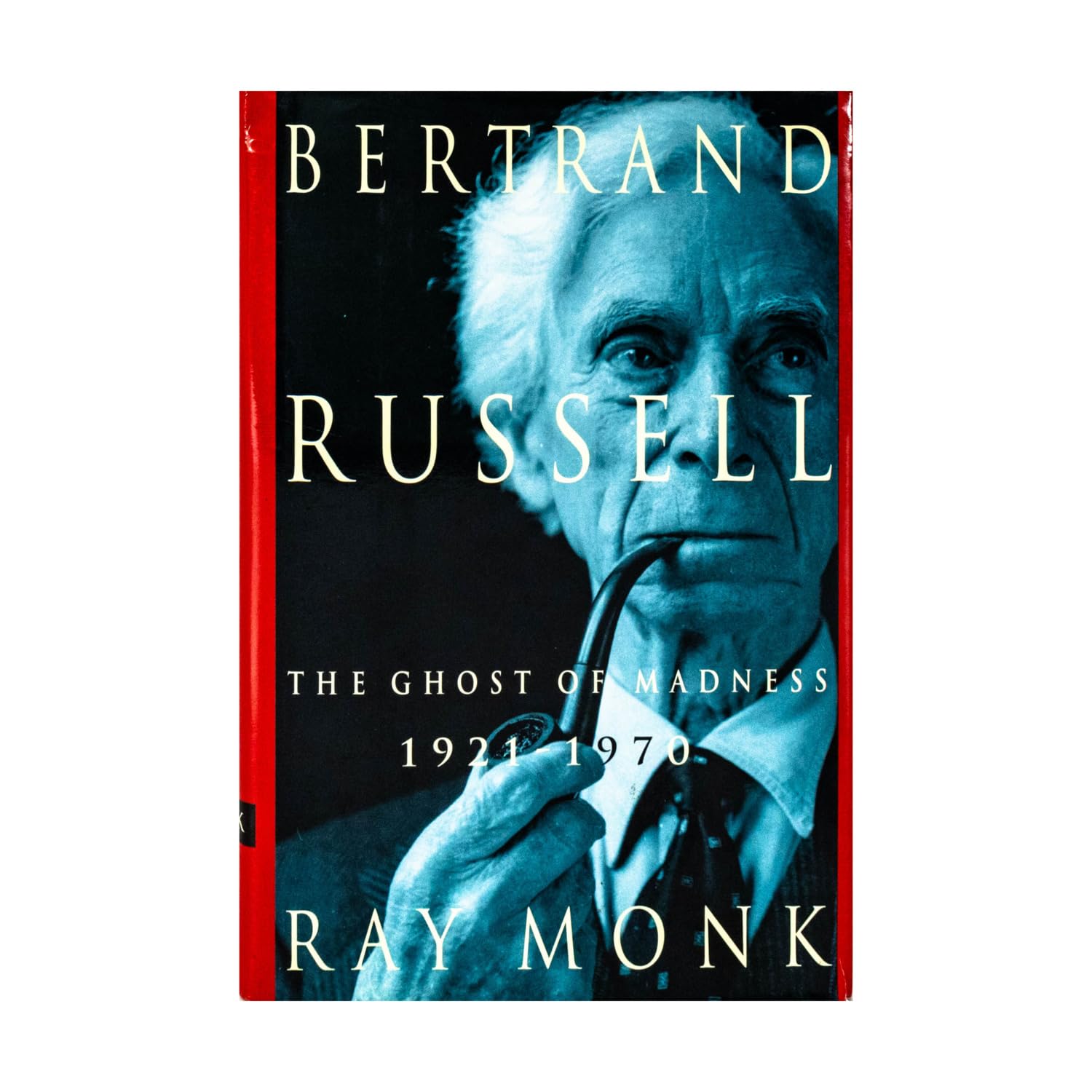

A portrait of the twentieth-century philosopher focuses on Russell's academic accomplishments, and his failed attempts to apply reason to his personal relationships and the problems of everyday life. This rich, variegated biography (Monk's second and final volume after The Spirit of Solitude, 1872-1921) starts off on a happy note for Russell, with his second marriage (of four) and the longed-for birth of a son. Unfortunately, from that point on, things only go downhill for him emotionally. Throughout his life, Russell (1873-1970) felt that he might go insane. He believed very much in romantic love but was apparently incapable of truly loving anyone. This emotional insecurity led him to multiple liaisons outside of his marriages (at the age of 64, his third marriage was to a 20-year-old) and strained relationships with his two children. Particularly upsetting to Russell was the homosexuality of his son, since he was on record as saying that homosexuality was the consequence of bad parenting. These domestic problems aside, Monk does a marvelous job of covering the highlights of the last half of Russell's long life: his Nobel prize in literature, the Russell-Einstein Manifesto against nuclear proliferation, his imprisonment for antinuclear protests, his social and political philosophy, and his contributions to logic and analytic philosophy. Highly recommended for academic and public library collections. Leon H. Brody, U.S. Office of Personnel Management Lib., Washington, DC Copyright 2001 Reed Business Information, Inc. One of the great logicians of modern times, Bertrand Russell lived a life that defies all syllogisms. In the second volume of what is sure to establish itself as the definitive biography, Monk lays bare the strange paradoxes that bedeviled the great philosopher during the last six decades of his very long life. Careful scholarship shreds the illusion of success created by Russell's elevation to the Order of Merit and by his surprising selection for a Nobel Prize in literature. What then stands exposed is the conceptual confusion that increasingly clogged Russell's public pronouncements in his later years, as well as the personal betrayals that poisoned his private life. It is thus a figure of tragedy not triumph that Monk limns in this nuanced chronicle, recounting how Russell lost his grip on serious philosophy, squandered his literary gifts in hack journalism, repeatedly failed in his marital and parental relationships, and embarrassed himself in his politics. To be sure, it is still a modern titan that Monk shows his readers--one who deflected the lives of Einstein, Eliot, and Trotsky. But it is a titan who ascended to the pantheon shrouded in shadows of pathos. Sure to endure as a standard reference for decades. Bryce Christensen Copyright © American Library Association. All rights reserved The Sunday Telegraph In its seriousness, its intelligence, and sheer narrative drive, one of the outstanding biographies of our time. -- Review Ray Monk is the author of Ludwig Wittgenstein: The Duty of Genius, for which he won the Mail on Sunday /John Llewellyn Rhys Prize and the Duff Cooper Award, and Bertrand Russell: The Spirit of Solitude. He is Professor of Philosophy at the University of Southampton in England. Chapter One: Fallen Angel: Russell At Forty-Nine 'My brain is not what it was. I'm past my best -- & therefore, of course, I am now celebrated.' As Russell approached his fiftieth birthday, this was the kind of wittily self-deprecating remark he was prone to make. On this occasion he was speaking to Virginia Woolf, next to whom he found himself sitting on 3 December 1921 at a dinner party in Chelsea given by his old Cambridge friend (now a successful and wealthy barrister) Charles Sanger. Sitting among such friends, Russell could not help but be deeply conscious of the fact that he had changed a great deal since the days when he and Sanger had been mathematics students together thirty years earlier, and, under Virginia Woolf's gentle but persistent prompting ('Bertie is a fervid egoist,' Woolf wrote that night in her diary, 'which helps matters'), he began to reflect on these changes. He still regarded mathematics as 'the most exalted form of art', he told her, but it was not an art that he himself expected ever to practise again: 'The brain becomes rigid at 50 -- & I shall be 50 in a month or two' (actually, he would be fifty the following May). He might write more philosophy, he said, but 'I have to make money', and so most of his writing would henceforth be paid journalism. The days when he could devote himself solely to serious intellectual work were over. Between the ages of twenty-eight and thirty-eight, he told Woolf, he had 'lived in a cellar & worked', but then 'my passions got hold of me'. Now, he had come to terms with himself, and 'I don't expect any more emotional experiences. I don't think any longer that something is going to happen when I meet a new person.'