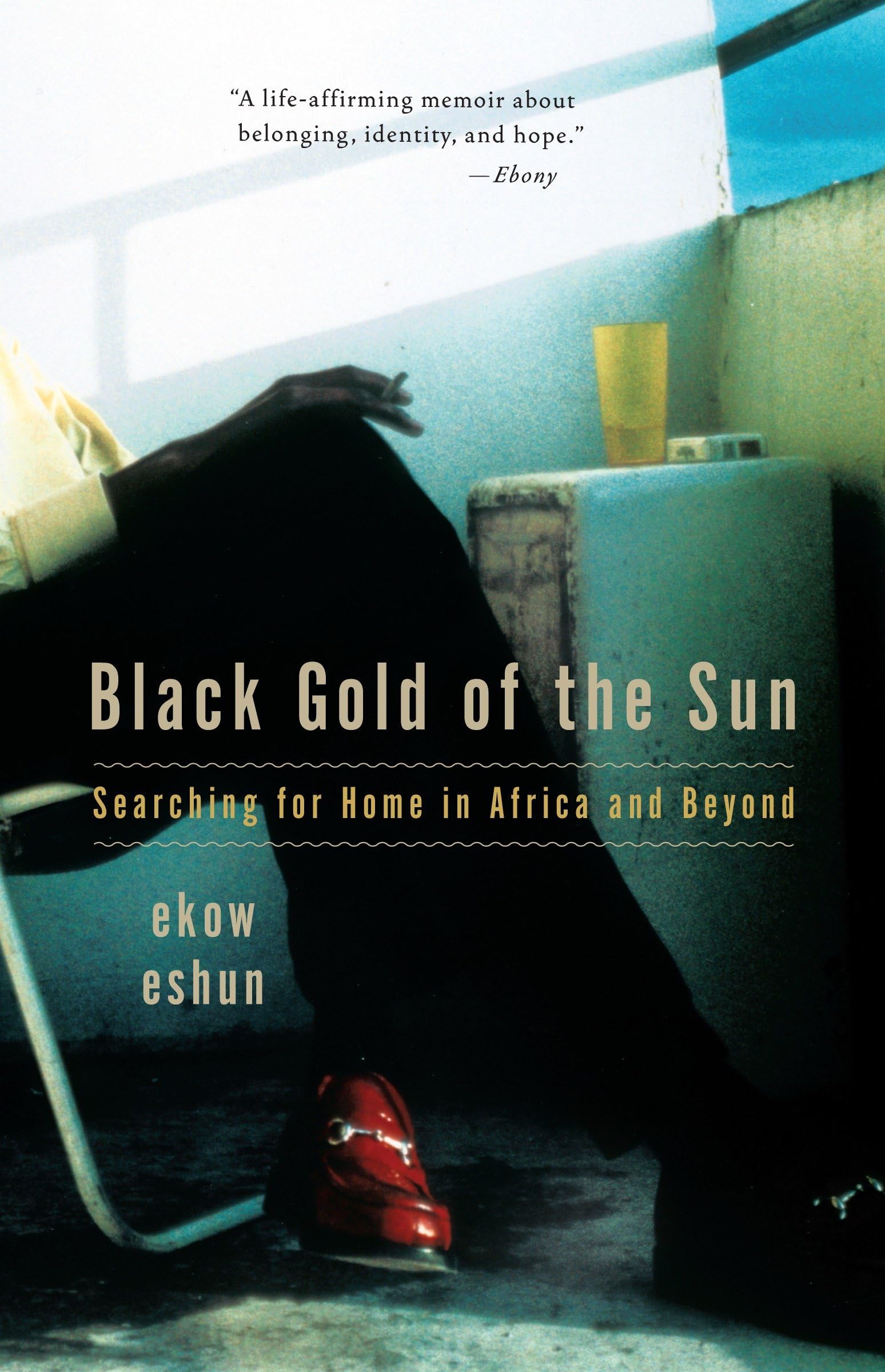

At the age of thirty-three, Ekow Eshun—born in London to African-born parents—travels to Ghana in search of his roots. He goes from Accra, Ghana’s cosmopolitan capital city, to the storied slave forts of Elmina, and on to the historic warrior kingdom of Asante. During his journey, Eshun uncovers a long-held secret about his lineage that will compel him to question everything he knows about himself and where he comes from. From the London suburbs of his childhood to the twenty-first century African metropolis, Eshun’s is a moving chronicle of one man’s search for home, and of the pleasures and pitfalls of fashioning an identity in these vibrant contemporary worlds. “A life-affirming memoir about belonging, identity, and hope.” — Ebony “An impressive debut. . .An unusual memoir in which the personal and the political are entwined with great skill.” — The Times (London)“Leavened with insight, self-awareness, and flashes of humor . . .Eshun is a skilled wordsmith.” — Christian Science Monitor “Refreshing. . .Eshun’s writing is fluid and self-assured. . .his wistfulness and wry sense of humor add to the book’s charm. . .an engaging and eye-opening account of one man’s journey toward self-discovery.” — Black Issues Book Review Ekow Eshun is a former editor of the British men's magazine Arena and is now artistic director of the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London, where he lives. This is his first book. I 'Where are you from?' he said. 'No, where are you really from?' It was the businessman who wanted to know. He'd been slumped beside me with his eyes shut and his mouth open since we'd left London. As the Boeing 777 dipped towards Accra he heaved himself up straight. 'Where are you from?' he repeated. The overhead light glistened off the darkness of his skin. He wiped the film of sweat from his forehead. I gave him the usual line. 'My parents are from Ghana, but I was born in Britain.' In all the times I'd been asked the same question it was still the best answer I'd come up with. It wasn't a lie. It just wasn't the whole truth. 'Then you are coming home, my brother,' he said, leaning across me to empty a miniature of Teacher's Scotch into the plastic glasses on our foldaway tables. 'Akwaba,' he said, raising his glass. 'Welcome home.' As we drained the whisky I thought of all the other ways I could have answered his question. Where are you from? I don't know. That's why I'm on this plane. That's why I'm going to Ghana. Because I have no home. I'd caught the plane that afternoon: a British Airways flight straight down the Greenwich Meridian line from Heathrow to Kotoka airport in Accra. We'd risen above the clouds and, seated over the wing with the whine of the jet engines in my ears, I'd tried to concentrate on an anodyne movie about a gang of con artists breaking into the vault of a Vegas casino, before giving up to watch the plane's shadow ripple against the clouds below instead. At Lagos, the flight made a stopover, and I caught my first glimpse of Africa since childhood. The sun was low and from out of the shadows ground crew in blue overalls hastened across the tarmac. A staircase thunked against the plane's flank. The doors sighed open. Tropical warmth filled the cabin. A stewardess with brittle make-up sprayed gusts of rose-scented insect repellent along the aisle. 'They treat us like animals,' grumbled the businessman. A line of passengers in heavy cloth robes joined the plane, haloed with sweat. I compared their faces to mine. I looked as African as they did. But I didn't know how far that affinity stretched. Did it reach beneath the skin or did it end on the surface, in the slant of our eyes and the fullness of our lips? It was April 2002, and I was thirty-three years old. I was flying to Ghana to find out what I was made of. My name is Ekow Eshun. That's a story in itself. Ekow means 'born on a Thursday'. The Ghanaian pronunciation of it is Eh-kor and that would be fine if I'd grown up there instead of London where, to the ears of friends, Ehkor became Echo. Throughout my childhood I was pestered by schoolyard wags who thought it hilarious to call after me in descending volume: 'Echo, echo, echo.' It was my first lesson in duality. Who you are is determined by where you are. My parents arrived in London from Ghana in 1963. They never meant to stay. And even though they have spent most of the past forty years in Britain, Ghana is still their home. When I was a child growing up in London, its sounds and smells pervaded our house. Ghana was there in the hot pepper scent of palm nut soup tickling your nostrils as you entered the house; the highlife songs rising from the stereo; the sound of my mother shouting down a capricious telephone line to her sister in Accra. But Ghana was their home, not mine. I knew this from experience. I was born in 1968 in a red-brick terraced house in Wembley, north London. I was the youngest of fo