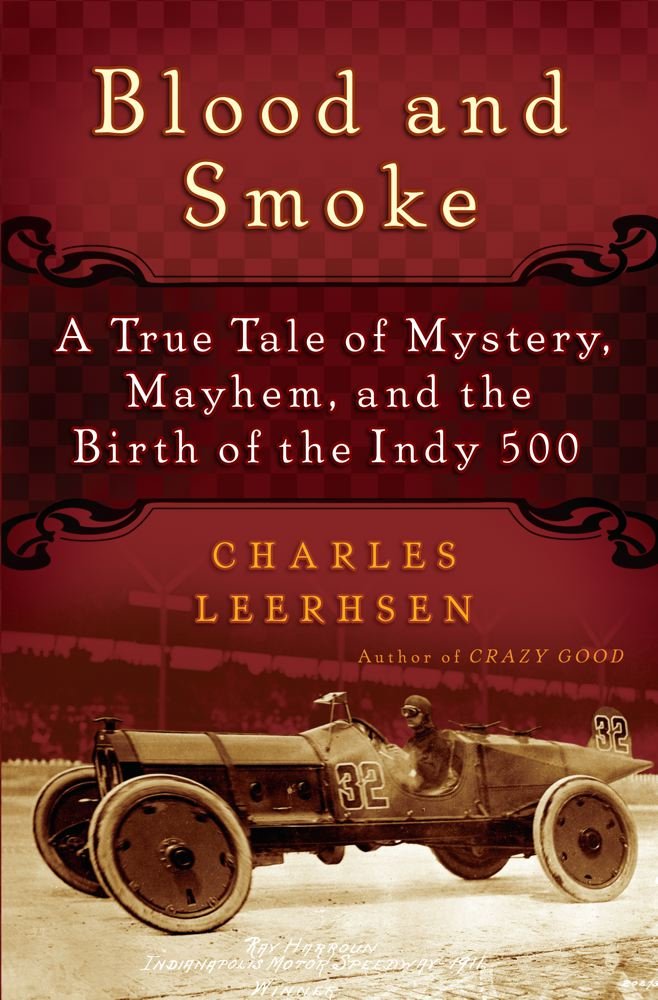

Blood and Smoke: A True Tale of Mystery, Mayhem, and the Birth of the Indy 500

$26.00

by Charles Leerhsen

Shop Now

Forty cars lined up for the first Indianapolis 500. We are still waiting to find out who won. The Indy 500 was created to showcase the controversial new sport of automobile racing, which was sweeping the country. Daring young men risked life and limb by driving automobiles at the astonishing speed of 75 miles per hour with no seat belts, hard helmets, or roll bars. When the Indianapolis Speedway opened in 1909, seven people were killed, some of them spectators. Oil-slicked surfaces, clouds of smoke, exploding tires, and flying grit all made driving extremely hazardous, especially with the open-cockpit, windshield-less vehicles. Most drivers rode with a mechanic, who pumped oil manually while watching out for cars attempting to pass, and drivers would sometimes throw wrenches or bolts at each other during the race. The night before an event the racers would take up a collection for the next day?s new widows. Although the 1911 Indy 500 judges declared Ray Harroun the official winne Charles Leerhsen was formerly an executive editor at Sports Illustrated . He has written about sports and culture for Newsweek, Rolling Stone, Esquire, The New York Times, and People , as well as SI . A native of the Bronx, he now lives in Brooklyn with his wife, the writer Sarah Saffian. 1 UNTIL THE MOMENT that one ran over his breastbone, Clifford Littrell had been exceedingly fond of automobiles. To be sure, a lot of young people were car-crazy in 1909, endlessly debating the relative merits of the National, the Pierce-Arrow, and the Knox, fogging the windows at the McFarlan showroom with their Sweet Caporal–scented sighs, scanning the glossy pages of The Horseless Age for gossip about rumored innovations like windshields and black tires (as opposed to the standard, tiresome off-white)—and digging through bins at dry goods emporiums for the latest in silk driving scarves (for men) or the kind of cunning little riding bonnet sported by Lottie Lakeside in the hit Broadway musical The Motor Girl. But Littrell was no mere enthusiast. No, this poor fellow—whom we come upon writhing in the bustling intersection of Capitol Avenue and Vermont Street in Indianapolis, Indiana, at 11:30 on the sunny, sticky morning of Tuesday, August 17—had dedicated his life to what was then known as autoism. At the age of twenty-seven, he had risen from the position of molder in a metal factory to what was then known as a mechanician. His main job was to road-test motorcycles, which is what some Americans who disdained the French word automobile (because it was French) then called cars. It was still so early in the motor age, you see—three years before the Stutz Bearcat and four before the Duesenberg—that people hadn’t quite worked out the terminology. A corpse was a corpse, though, and the prospect of seeing one caused a crowd to gather. Littrell was no one they knew, they could see, yet no mysterious stranger, either, having just come loose from the noisy caravan of men and equipment heading to the not-quite-finished Indianapolis Motor Parkway—or rather Speedway , as they had been calling it these last couple of months—some five miles northwest of town. A long line of Jacksons, Marmons, Amplexes, Buicks, and other cars had been traveling there, circus-train-style, the better to attract attention and whip up curiosity as they prepared for a historic event: the first racing meet in America conducted on a track built specifically for automobiles. Thousands of auto industry people—executives, salesmen, and common laborers like Littrell—had flocked to Indianapolis that week for three days of competition that would begin the next afternoon and culminate in the first edition of the 300-mile Wheeler-Schebler race on Saturday, August 21. Littrell worked for Stoddard-Dayton of Dayton, Ohio, one of more than a thousand auto manufacturers then trying to grab a share of the booming U.S. market. Most of those car companies were tiny operations—some were virtual one-man shops—but Stoddard-Dayton ranked among the largest, with several hundred employees. Littrell had started there about five years before, when the company, instead of turning out “Touring cars with Speed and Symmetry in every line,” as their literature boasted, was instead still making mowers, hay rakes, and harrows. That morning he had been perched on the rear of the company’s highly touted No. 19 race car as it rolled out of the garage. It was a precarious spot, atop the gas tank with no handle to grasp, but the trip to the Speedway seemed relatively short, and the traffic, a mix of horse-drawn and motorized vehicles, was moving sluggishly; he thought he would be all right. Then he remembered a wrench he had left behind, and, without informing the driver, he braced himself to hop off the vehicle, figuring he would grab the tool, catch up to the car, and quickly clamber back aboard. Just at that moment, though, the traffic jam eased a bit, the No. 19 car surged forward, and Littrell, w