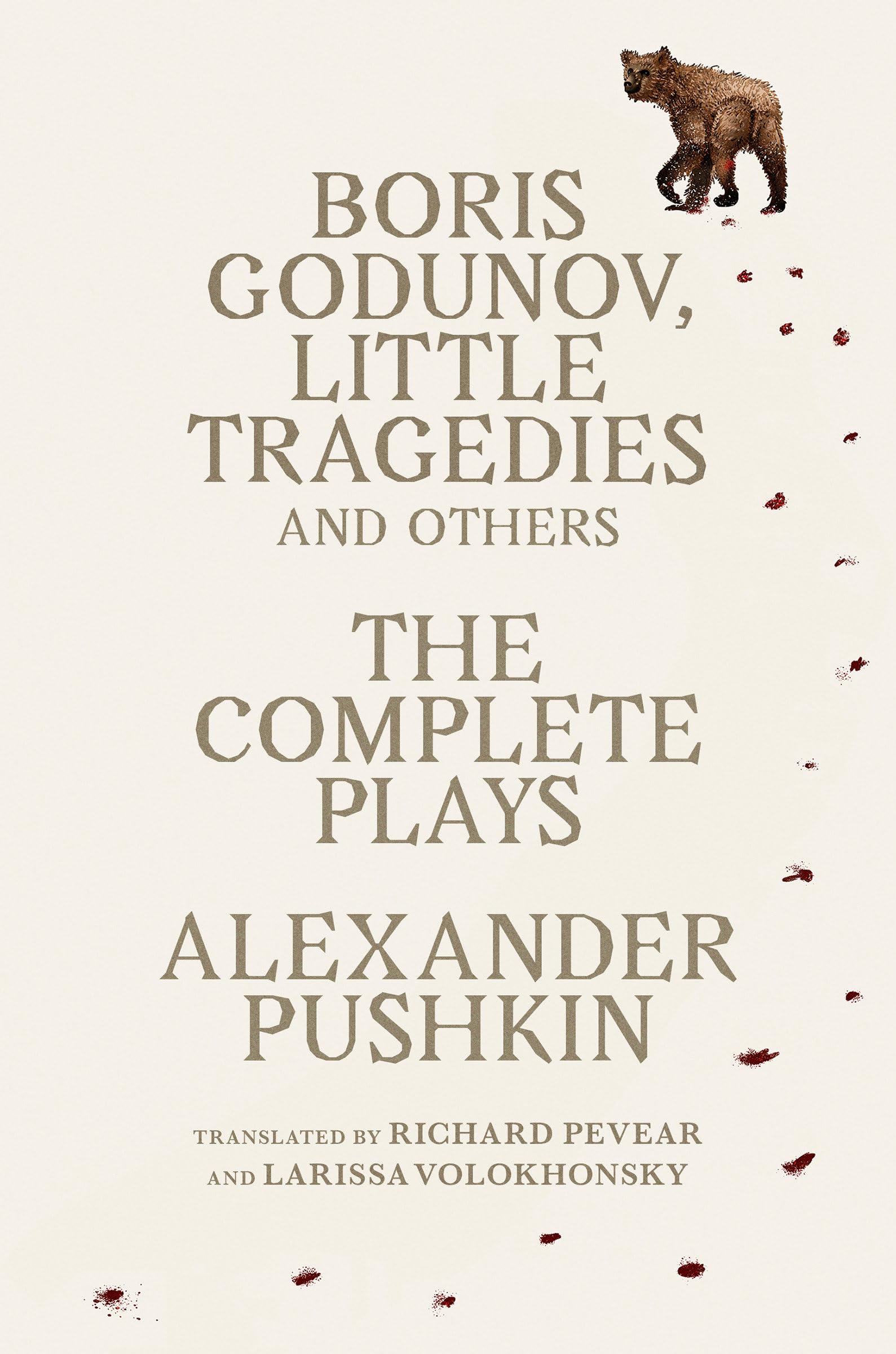

Boris Godunov, Little Tragedies, and Others: The Complete Plays (Vintage Classics)

$11.33

by Alexander Pushkin

Shop Now

The award-winning translators bring us the complete plays of the most acclaimed Russian writer of the Romantic era. Known as the father of Russian literature, Alexander Pushkin was celebrated for his dramas as well as his poetry and stories. His most famous play is Boris Godunov (later adapted into a popular opera by Mussorgsky), a tale of ambition and murder centered on the sixteenth-century Tsar who preceded the Romanovs. Pushkin was inspired by the example of Shakespeare to create this panoramic drama, with its richly varied cast of characters and artful blend of comic and tragic scenes. Pushkin’s shorter forays into verse drama include The Water Nymph , A Scene from Faust , and the four brief plays known as the Little Tragedies : The Miserly Knight , set in medieval France; Mozart and Salieri , which inspired the popular film Amadeus ; The Stone Guest , a tale of Don Juan in Madrid; and A Feast in a Time of Plague , in which a group of revelers defy quarantine in plague-ridden London. These new translations of the complete plays, from the award-winning translators Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky, freshly reveal the range of Pushkin’s enduring artistry. ALEXANDER PUSHKIN (1799–1837) was a poet, playwright, and novelist who achieved literary fame before he was twenty. He was born into the Russian nobility and his great-grandfather was the African-born general Abram Petrovich Gannibal. Pushkin’s radical politics brought him censorship and periods of banishment, but he eventually married a society beauty and became part of court life. Notoriously touchy about his honor, he died at age thirty-seven in a duel with his wife’s alleged lover. About the Translators: RICHARD PEVEAR and LARISSA VOLOKHONSKY have translated works by Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, Chekhov, Gogol, Bulgakov, Leskov, and Pasternak. They were twice awarded the PEN/Book-of-the-Month Club Translation Prize (for Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov and Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina ). They are married and live in France. From the Introduction by Richard Pevear Figlyarin, sitting at home, decided That my black grandfather Gannibal Was bought for a small jug of rum And fell into some skipper’s hands. That skipper was the glorious skipper By whom our country was set moving, Who turned the rudder of our native ship Forcefully onto its majestic course. —Pushkin, “Post Scriptum” Peter the Great (1672–1725), the last tsar and first emperor of Russia, was the “glorious skipper” who forcefully turned his country to the West, and in 1703, on a stretch of marshland facing the Gulf of Finland, began to build the city of St. Petersburg, giving Russia a major seaport open to Europe. “Finally Peter appeared . . . Russia entered Europe like a ship launched with the blow of an axe and the thunder of cannons.” So Pushkin wrote in an unfinished essay entitled “On the Insignificance of Russian Literature” (1834). Pushkin was to play a similar role in that literature to the role Peter played in Russian history, and with as enduring an effect on its significance. Throughout his work, Pushkin remained in complex relations with Peter: in his unfinished first novel, The Moor of Peter the Great (1828), portraying his black great-grandfather on his mother’s side, Abram Petrovich Gannibal (1696–1781), the son of a Central African prince, who was captured by the Turks as a boy, sold into slavery, and then sent to Russia, where he was personally adopted by Peter (hence his patronym), and was eventually granted nobility and high military rank; in the narrative poem Poltava (1829), dealing with the decisive battle in which Peter’s forces defeated the Swedish army and made Russia the leading nation of northern Europe; in his last long poem, The Bronze Horseman (1833), in which the mounted statue of Peter the Great on Senate Square in Petersburg comes ominously to life, at least in the deranged mind of the poem’s hero, and goes galloping after him through the city. Alexander Pushkin (1799–1837) was born a poet, but he became a master of prose and drama as well, and it was the body of his work as a whole that set Russian literature on its new course. In particular, he was intent on reforming Russian drama, a task he outlined in drafts of an introduction to his first play, Boris Godunov , and in an article “On National Drama,” both written in 1829–1830 and both left unpublished. In the latter he raises the question directly: Can our tragedy, formed on the example of Racinian tragedy, lose its aristocratic habits? How can it move “from its measured, orderly, dignified, and polite dialogue to the crude frankness of popular passions, to the freedom of public-square opinions? How can it suddenly drop its obsequiousness, how can it do without the rules it is used to, without the forced accommodating of everything Russian to everything European; where, from whom can it learn an idiom comprehensible to the people? W