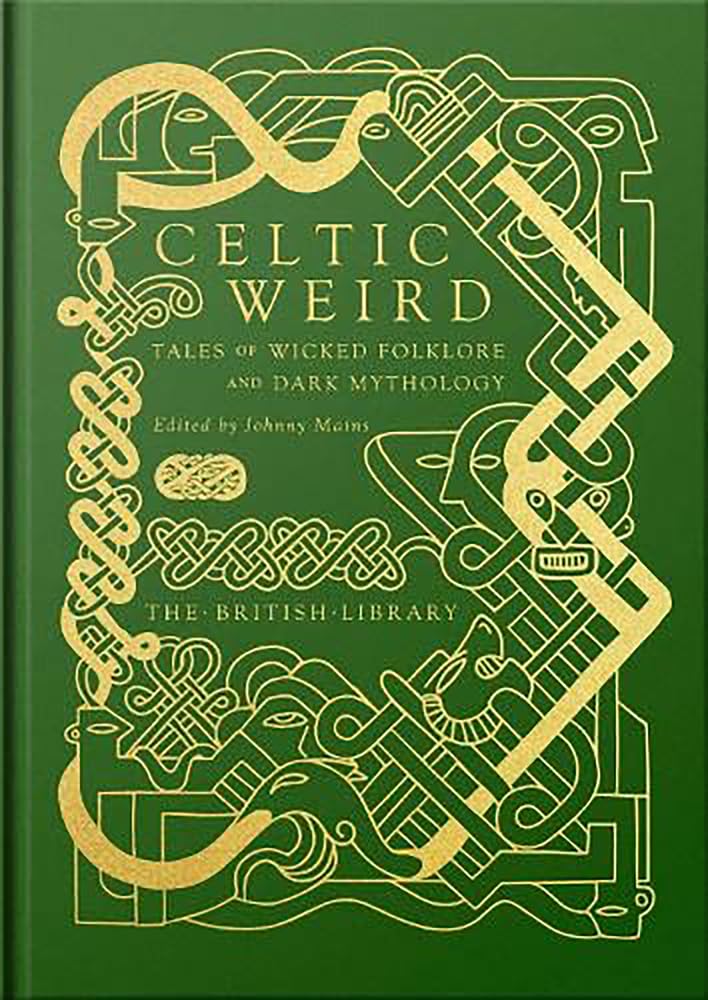

Celtic Weird: Tales of Wicked Folklore and Dark Mythology (British Library Hardback Classics)

$23.27

by Johnny Mains

Shop Now

Once I thought I glimpsed her high up in a bush, like dirty rags in a gale. Not that so far there has been any gale, or even any wind. The total silent stillness is one of the worst things. Yes, it is a battle with strong and unknown forces that I have on my hands. From the shorelines, hills and towns of ancient lands, tales of twisted creatures, sins against nature and pagan revenants have been passed down from generation to generation. In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, folklore from Wales, Scotland, Ireland, Cornwall, Brittany and the Isle of Man inspired a new strain of strange short stories, penned by writers of the weird and fantastic including masters of the form such as Arthur Machen, Edith Wharton and Robert Aickman. In this volume, Johnny Mains dives into the archives to unearth a hoard of twenty-one enthralling tales imbued with elements of Celtic folklore, ranging from the 1820s to the 1980s and including three weird lost gems translated from Gaelic . Together they conjure uncanny visions of eternal forces, beings and traditions, resonating with the beguiling essence of this unique branch of strange fiction. Johnny Mains is an award-winning editor renowned for recovering lost stories from the archives. His focus for the past few years has been stories by female authors, many of which have been published in the Black Shuck Books anthologies A Suggestion of Ghosts and An Obscurity of Ghosts . Mains has also edited collections of the best contemporary British Horror, and co-edited the Dead Funny anthologies of short stories by contemporary comedians with Robin Ince. I N T R O D U C T I O N Celtic myths and folklore have always been extremely weird. In Ireland there is Balor, the Demon King, tyrant leader of the Fomorians. He had one eye, which could kill you if he opened it and always had to keep that one eye closed to stop him tripping over all of the dead bodies in his wake. There’s also the tale of Angelystor, the Welsh spectre who lives under a 3,000-year- old yew tree and announces the names of those who will soon meet their doom. The Welsh also have, alongside the Cornish and Bretons, Ankou, the servant of death and the first child of Adam and Eve who is doomed to collect the souls of others before he himself can go to the afterlife. The Scots have the Mester Stoor Worm, a sea serpent who can destroy humans and animals with its stinking breath. And finally, in the Isle of Man, there is the Buggane, a massive ogre who couldn’t cross water but sported a large red mouth and huge tusks. Many of those myths, told in the oral tradition, were the ancient ances- tors of the Celtic Revival tradition, where they were rescued and studied and debated and the concept of Celtic identity became a pulsing, living concept and the legends, folklore and poetry became forever locked in Celtic DNA. From there, one would have thought that the languages of the ancient tribes would have been brought back from the brink and would have flour- ished and have been a part of everyday culture. Alas, while people may like to buy stickers and fridge magnets of Celtic crosses, native languages are on the brink. In 2020 a study concluded that only 10,000 of 50,000 Gaels spoke Gaelic as an everyday language,*less than 1,000 people speak Cornish,†and French government policies have given little support to preserving the Breton tongue—even though there are currently half a million speakers, most of them are over sixty years of age. In Ireland and Wales the numbers are better, but it can simply take a few generations of neglect on the behalf of authorities for those numbers to plummet. While the languages that form the Celtic traditions may be dying, there is still a keen interest in the historical study of traditions and folklore. This volume is a tribute to the many works that have come before it. In 1905, the Celtic Revival was in full swing, with a magazine called the Celtic Reviewleading the charge, aiming to present a journal which was ‘for the social, religious and literary history not only of the Celtic races themselves, but also of the many people with whom they came into contact during the long centuries in which the Celts have influenced so strongly the Western world’, but it came with the sad understanding that ‘the study of Celtic literature of the past opens a wide yield of investigation as yet comparatively untouched’. But nine years after 1905, there was of course the Great War which culled many Celtic voices and historians. Traditions that had been given and were to be passed down to future generations, instantly snuffed out by the cruel machineries of man, in turn creating their own awful lore. Then the Second World War compounded an already decimated landscape. We recover. The stories come back; they always do. Folk tales, myths and legends are interpreted by different generations in different ways. Sometimes you can see their influence, other times, maybe only a whisper. And that’s where researc