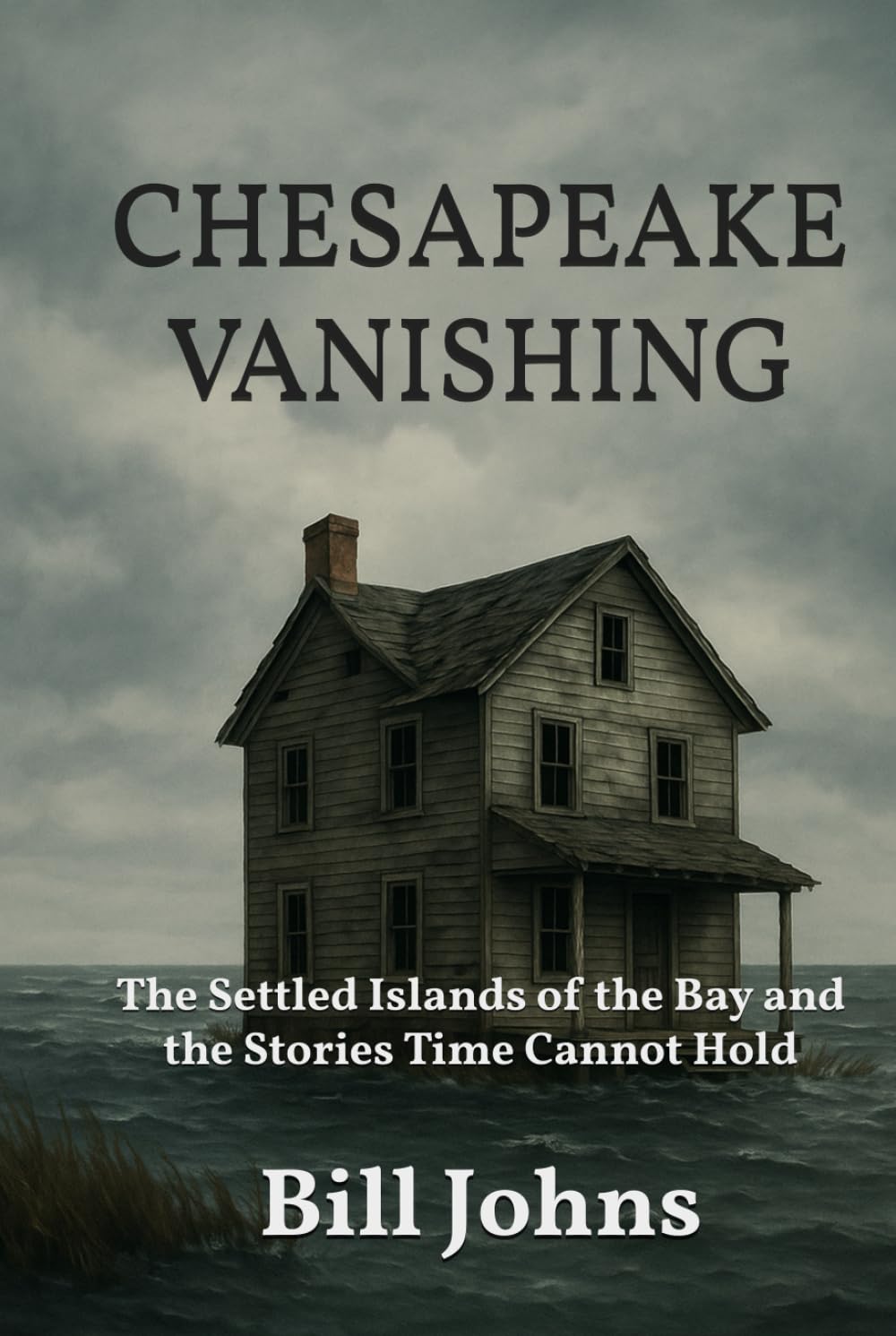

Chesapeake Vanishing: The Settled Islands of the Bay and the Stories Time Cannot Hold (Chesapeake Unwritten)

$34.95

by Bill Johns

Shop Now

Along the shrinking shorelines of Smith Island, Deal Island, Tangier, and Holland, the Chesapeake Bay’s most intimate histories are disappearing—but not without a trace. Chesapeake Vanishing is a haunting, deeply researched cultural history that explores the stories the tide cannot carry away. From the colonial founding of Kent Island to the retreat of Holland’s last house into the sea, Bill Johns traces the Chesapeake’s settled islands not as nostalgic curiosities but as vibrant, contested landscapes shaped by faith, labor, and loss. Drawing from land patents, oral histories, wills, sermons, dialect surveys, NOAA maps, and the tidal rhythms of daily life, Chesapeake Vanishing documents what remains when a place is no longer held by land—but still held by memory. Each chapter moves through the layered textures of island life: the spiritual cadence of watermen’s faith on Hoopers Island; the faint but persistent traces of enslaved laborers on the margins of South Marsh; the voices of grandmothers who never needed a new calendar because “they already knew the days.” The islands are not treated as relics, but as living archives—fragments of a world that understood tide before clock, voice before record, and shoreline as inheritance rather than possession. These are not metaphorical vanishings. The Chesapeake loses thousands of acres every year to erosion, subsidence, and sea-level rise. But what’s being lost is not just ground—it’s grammar. Dialects fade. Cemeteries collapse into marsh. Recipes, prayers, and weather-sense erode with every outmigration. Johns moves with the patience of a documentarian and the eye of a poet, careful not to simplify the brutal, beautiful intricacies of island life. He visits crab shacks where retired Baltimore cops work pressure steamers and recounts the moment a man in a long-unfashionable Peters jacket, scrawled with “Elvis is King,” becomes an emblem of informal archival persistence. The book is as much about what islands carry as what they can no longer hold. Chesapeake Vanishing follows the Bay through three centuries of transformation: from Indigenous networks of seasonal use to the forced labor of enslaved people on oyster middens; from skipjack fleets and crab pickers to ghost islands and FEMA charts. Some chapters read like folklore, others like legal history. All resist easy eulogy. What Johns offers is not preservation, but presence—a map of what still lingers, if we know how to see it. For readers of Chesapeake history, climate nonfiction, American folklore, and maritime ethnography, this book joins the shelf alongside Tom Horton, Earl Swift, and Chesapeake-native Gilbert Byron. But it stands alone in its narrative ambition: to give the disappearing islands their own voice, unmarred by pity or spectacle. Chesapeake Vanishing is an act of listening. And for those willing to follow its currents—to learn the old names, to walk the vanishing paths, to remember what the tide will not return—it offers more than a record. It offers a reckoning.