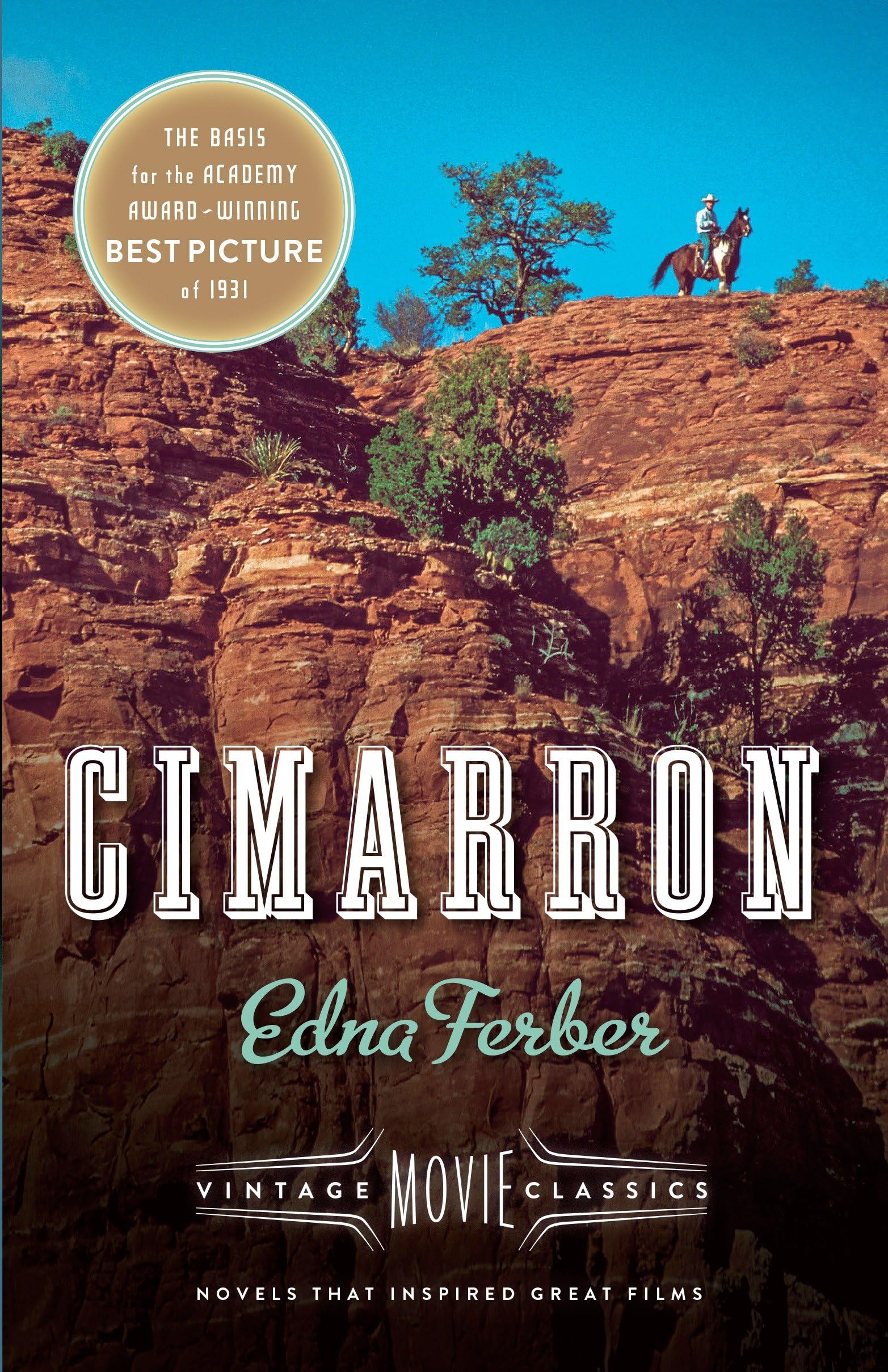

The basis for the Academy Award-winning major motion picture starring Best Actor nominee Richard Dix and Best Actress nominee Irene Dunne. This vivid and sweeping tale of the Oklahoma Land Rush, from Pulitzer Prize winner Edna Ferber, traces the stunning challenges of settling an untamed frontier. Staking claim to their new home in Osage, Yancey Cravat, a spellbinding criminal lawyer, and his wife, well-bred Sabra, work against seemingly overwhelming odds to create a prosperous life for themselves. And as they establish themselves in this lawless land, Sabra displays a brilliant business sense and makes a success of their local newspaper, the Oklahoma Wigwam , all amidst border and land disputes, outlaws, and the discovery of oil. Originally published in 1929, and twice made into a motion picture, Cimarron brings history alive, capturing the settling of the American West in vivid detail. With a new foreword by Julie Gilbert. Vintage Movie Classics spotlights classic films that have stood the test of time, now rediscovered through the publication of the novels on which they were based. Praise for Edna Ferber's Cimarron “A ripping yarn . . . a gorgeous piece of work.” — Saturday Review of Literature “The exuberance and gusto, the robust romanticism of Cimarron are so compelling. . . . Frankly glamorous, headlong in its story-telling fervor. . . . The story is traced against one of the most spectacular backgrounds in American life.” — The New York Times Book Review Edna Ferber was an American novelist, short story writer and playwright. Her bestselling novels were especially popular and included the Pulitzer Prize-winning So Big , Show Boat , Giant , and Cimarron , which was made into the 1931 film that won the Academy Award for Best Picture. She died in 1968. I All the Venables sat at Sunday dinner. All those handsome inbred Venable faces were turned, enthralled, toward Yancey Cravat, who was talking. The combined effect was almost blinding, as of incandescence; but Yancey Cravat was not bedazzled. A sun surrounded by lesser planets, he gave out a radiance so powerful as to dim the luminous circle about him. Yancey had a disconcerting habit of abruptly concluding a meal—for himself, at least—by throwing down his napkin at the side of his plate, rising, and striding about the room, or even leaving it. It was not deliberate rudeness. He ate little. His appetite satisfied, he instinctively ceased to eat; ceased to wish to contemplate food. But the Venables sat hours at table, leisurely shelling almonds, sipping sherry; Cousin Dabney Venable peeling an orange for Cousin Bella French Vian with the absorbed concentration of a sculptor molding his clay. The Venables, dining, strangely resembled one of those fertile and dramatic family groups portrayed lolling unconventionally at meat in the less spiritual of those Biblical canvases that glow richly down at one from the great gallery walls of Europe. Though their garb was sober enough, being characteristic of the time—1889—and the place—Kansas—it yet conveyed an impression as of purple and scarlet robes enveloping these gracile shoulders. You would not have been surprised to see, moving silently about this board, Nubian blacks in loincloths, bearing aloft golden vessels piled with exotic fruits or steaming with strange pasties in which nightingales’ tongues figured prominently. Blacks, as a matter of fact, did move about the Venable table, but these, too, wore the conventional garb of the servitor. This branch of the Venable family tree had been transplanted from Mississippi to Kansas more than two decades before, but the mid-west had failed to set her bourgeois stamp upon them. Straitened though it was, there still obtained in that household, by some genealogical miracle, many of those charming ways, remotely Oriental, that were of the South whence they had sprung. The midday meal was, more often than not, a sort of tribal feast at which sprawled hosts of impecunious kin, mysteriously sprung up at the sound of the dinner bell and the scent of baking meats. Unwilling émigrés, war ruined, Lewis Venable and his wife Felice had brought their dear customs with them into exile, as well as the superb mahogany oval at which they now sat, and the war-salvaged silver which gave elegance to the Wichita, Kansas, board. Certainly the mahogany had suffered in transit; and many of their Southern ways, transplanted to Kansas, seemed slightly silly—or would have, had they not been tinged with pathos. The hot breads of the South, heaped high at every meal, still wrought alimentary havoc. The frying pan and the deep-fat kettle (both, perhaps, as much as anything responsible for the tragedy of ’64) still spattered their deadly fusillade in this household. Indeed, the creamy pallor of the Venable women, so like that of a magnolia petal in their girlhood, and tending so surely toward the ocherous in middle age, was less a matter of pigment than of l