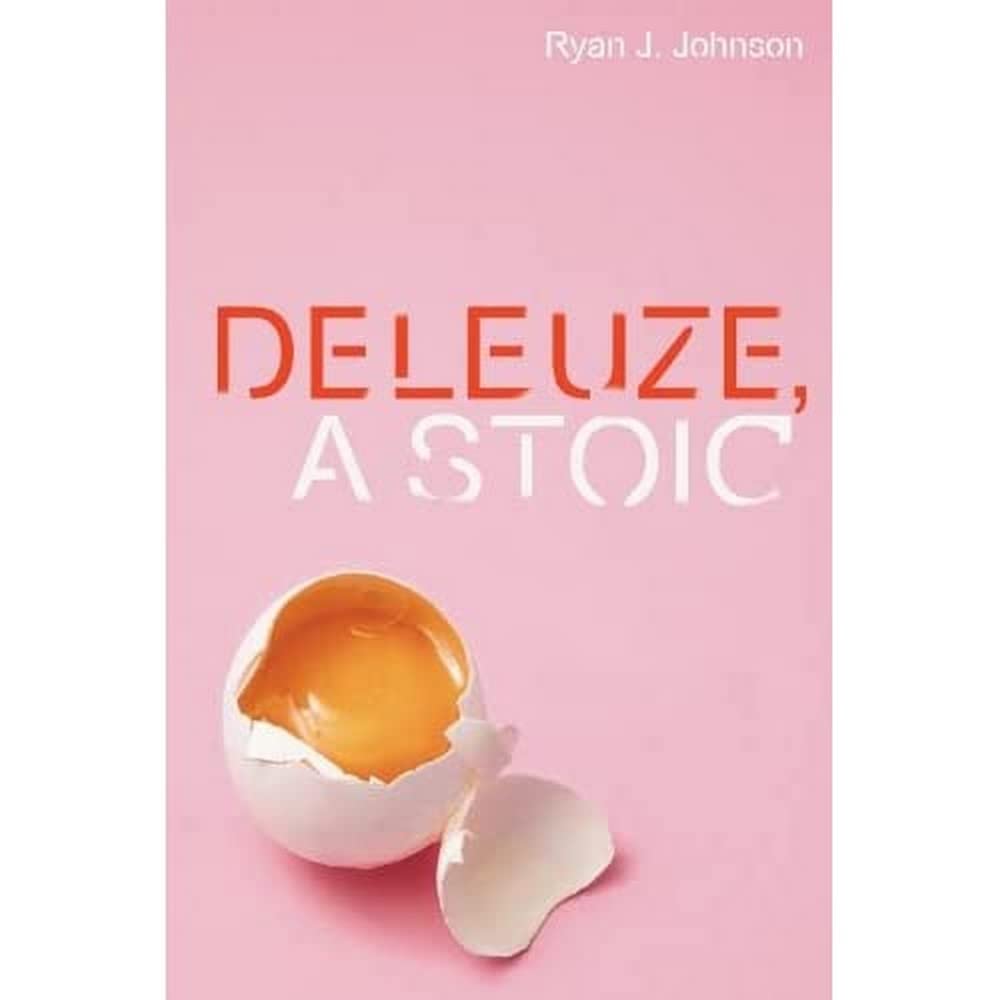

Deleuze dramatises the story of ancient philosophy as a rivalry of four types of thinkers: the subverting pre-Socratics, the ascending Plato, the interiorising Aristotle and the perverting Stoics. Deleuze assigns the Stoics a privileged place because they introduced a new orientation for thinking and living that turns the whole story of philosophy inside out. Ryan Johnson reveals Deleuze’s provocative reading of ancient Stoicism produced many of his most singular and powerful ideas. For Deleuze, the Stoics were innovators of an entire system of philosophy which they structured like an egg. Johnson structures his book in this way: Part I looks at physics (the yolk), Part II is logic (the shell) and Part III covers ethics (the albumen). Including previously untranslated French Stoic scholarship, Johnson unearths new possibilities for bridging contemporary and ancient philosophy. "Johnson has produced a profound and erudite study of the stoic roots of Deleuze's philosophy. This work is of vital importance for those interested in Deleuze, the continuing relevance of the stoic tradition, and, more fundamentally, the ethics of materialism." - Dr. Henry Somers-Hall, Royal Holloway, University of London Stoicism seems to be everywhere these days - bestseller lists, email blasts, social media posts, corporate training sessions. Stoicism seems just another self-help trend. But I think they all get it wrong. Stoicism is strange, very strange. I'd even call it perverse. This perversity is what I show in my book, Deleuze, A Stoic . To understand how strange it is, I draw upon Gilles Deleuze's taxonomy of ancient philosophical orientations. There are the pre-Socratics, thinkers of depth; the Platonists, thinkers of height, and Stoics, thinkers of surface. To this, we add the Aristotelians, thinkers of inwardness. First, the pre-Socratics, beginning with the legendary death of Empedocles. According to Diogenes Laertius, Empedocles 'set out on his way to Etna; then, when he had reached it, he plunged into the fiery craters and disappeared, his intention being to confirm the report that he had become a god.' Putting his metaphysics into practice, Empedocles jumped into the volcano, aiming to sink his body back into the primordial elements of nature from which it was birthed. Deleuze characterizes other pre-Socratics as equally thinkers of depths, with the difference being the element selected as the deepest of the depths: Thales' water, Anaximenes' air, Heraclitus' fire, etc. This metaphysical orientation is a 'turning below,' to the darkest matter, which what I call pre-Socratic subversion . Platonism moves in the opposite direction, up towards the heights. In the Republic, Deleuze see the 'philosopher is a being of ascents,' of escaping the cave and climbing toward the light (LS 127). Even after escaping the cave, the Platonist ascends higher still, up the divided line, into the clouds, or even above. Way up there, Plato locates the truly true beings, the so-called Forms. Like the sun, situated at the apex of the world, the Form of the Good establishes a vertical ontological order and upright intelligibility. Socratic dialectics is an education in how to ascend to the heights, to follow the 'flight of ideas' (LS 128). I call this Platonic conversion . Though Deleuze skips Aristotle, I see in him a variation on Platonic verticality. With important caveats, Aristotelianism is generally oriented upward along a vertical chain of being. For Aristotle, every thing and every way of being depends on a primary substance, which orients Aristotle towards the 'insides' of things. Aristotle thus 'takes down' what was, for Plato, above, placing it within the worldly particulars, and 'brings up' the depths of the pre-Socratics. The result: interiority or height-within. Scholars call it hylomorphism. I call it Aristotelian inwardness . The Stoics, however, are thinkers of surface. The Stoics do not simply return to the depths of primordial matter, nor do they erect a hierarchy reaching up into the heights, either above or within. Instead, they develop a new kind of ontological orientation - flatness. The Stoics are so strange. Though Deleuze sometimes suggests that it was Plato himself who provoked the overturning of Platonism, he also says that 'the Stoics...are the first to reverse Platonism' (DR 68, 244; LS 7). But even this is not quite right. For the Stoics do not reverse Platonism. They pervert it, along with all their other philosophical predecessors. Stoicism initiates a philosophical perversion . Deleuze, A Stoic begins with these four ancient philosophical orientations and it ends with five corresponding forms of ancient philosophical comedy (I add a fifth because one cannot speak of ancient comedy without including Diogenes) . To grasp the whole strange Stoic story, you must read the book. But to keep you interested, I will leave you with an aside on laughter that Deleuze made in a 1980 lecture.