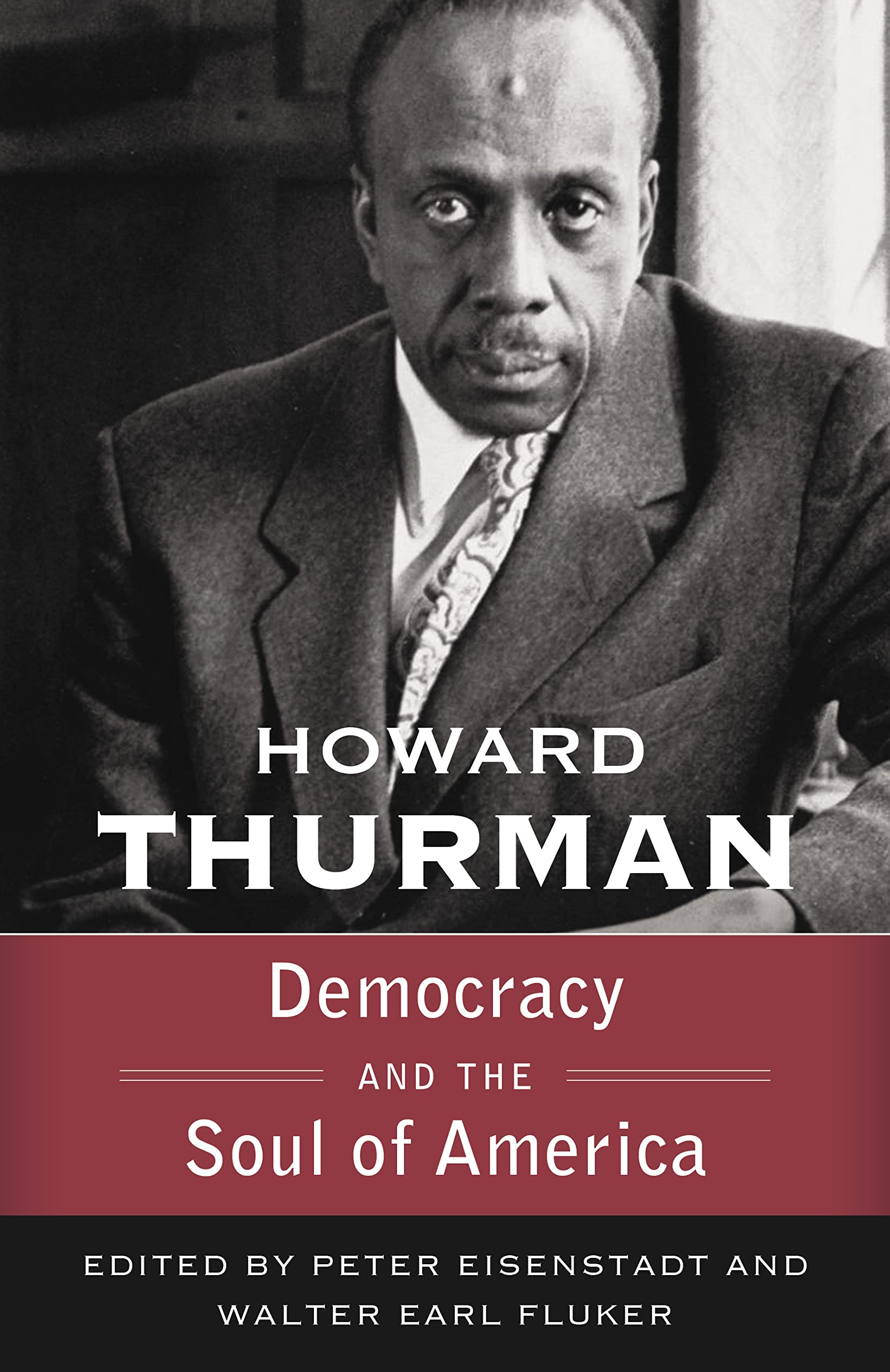

Democracy and the Soul of America (Walking with God: The Sermon Series of Howard Thurman)

$19.29

by Howard Thurman

Shop Now

Howard Thurman (1988-1981) was one of the leading religious thinkers of 20th century America, a mentor to the leaders of the civil rights movement, and a mystic who pioneered influential innovations in liturgy, worship, and spirituality in the quest for common ground. Walking with God will assemble the best of Thurman’s “sermon series,” all previously unpublished, in four volumes. This third volume will cover themes of Freedom, Democracy, and the Church (25 sermons). Walter Earl Fluker , senior editor of the Papers of Howard Washington Thurman and director of the Howard Thurman Papers Project, is Professor Emeritus of Ethical Leadership at Boston University and Dean’s Professor of Spirituality, Ethics and Leadership at Candler School of Theology. Peter Eisenstadt , associate editor of The Papers of Howard Washington Thurman, is author of Against the Hounds of Hell: A Life of Howard Thurman. Life, Liberty, and Loyalty Coming Alive to Democracy It has become, undoubtedly, Howard Thurman’s best-known quotation, beloved by life coaches and authors of self-help books. “Don’t ask yourself what the world needs. Ask yourself what makes you come alive, and go do that, because what the world needs is people who have come alive.”1 You can find it on greeting cards, in advertisements for upscale lines of clothing or housewares, or as a glossy motivational thought of the day, often with a backdrop of a rugged mountain or an inviting seascape, or with men and women jumping for joy with their arms outstretched. It has many admirers, along with a few detractors who have written to explain “Why I Hate That Howard Thurman Quote.”2 We do not hate it, exactly, but, if taken in isolation from the body of Thurman’s thought and work, it can be quite misleading. Putting aside its somewhat shaky provenance— its only source is a conversation that the Catholic scholar, Gil Baillie, remembered having with Thurman as a graduate student seeking advice on what needed to be done in the world. Thurman’s response might be good personal advice, implying that you should not let others set your life course, but it poorly represents his views on how one should respond to the needs of the world. Far more typical are statements such as the following from his 1939 lecture series, “Mysticism and Social Change.” The mystic, he states, “is forced to deal with social relations . . . because in his effort to achieve the good he finds he must be responsive to human need by which he is surrounded, particularly the kind of human need to which the sufferers are victims of circumstances over which, as individuals, they have no control, circumstances that are not responsive to the exercise of an individual will.” Thurman was always critical of self-absorption. “You can’t pursue happiness on a private race track,” he said in 1951, for its consequence would not be “a simple thing like unhappiness, but you get disintegration of soul.” (This he argued was at the root of capitalism and imperialism.)4 A decade later, in 1961, he argued that far too many Americans were focused on the “private fulfillment of [their] lives” to the exclusion of the “responsibility which we have to get acquainted with the facts of the world,” including its less attractive aspects, such as the nuclear arms race.5 From the time of his study of mysticism with Rufus Jones in the late 1920s Thurman was concerned with what he called the “thin line” between “a sense of Presence in your spirit” and “being a little off,” unable to connect to external realities with the urgency they demand.6 Although he was heartened by the revival of meditation and spirituality in the 1970s he also worried that a too fervent practice of the “mysticism of the life within” could lead to an unbalanced inwardness and could lead to shirking of responsibility for one’s society and its problems.7 In general, it was Thurman’s firm belief that “men are made great by great responsibilities,” and without them they “lack a sense of responsibility for the common life” and their internal morale and sense of identity can shrivel. In the end, perhaps, there is no real contradiction between the two perspectives on personal and spiritual commitment. Perhaps what Thurman was saying to Baillie was that if you start by asking the world what it needs, you will never find your answer. To know others, first know thyself.9 This is not an invitation to selfishness, but instead a pathway to finding your deeper connections to the people who sustain you, and to the web of interlocking communities that constitutes humanity. When you find what makes you come alive, you become the channel “through which the knowledge, the courageousness, the power, the endurance needful to meet the infinite needs of the world must flow.”10 Thurman gave this process many names: “detachment,” “relaxation,” “centering down,” and “affirmation mysticism.” It is also at the heart of Thurman’s vision of democracy, as articulated in the sermons and lectures pub