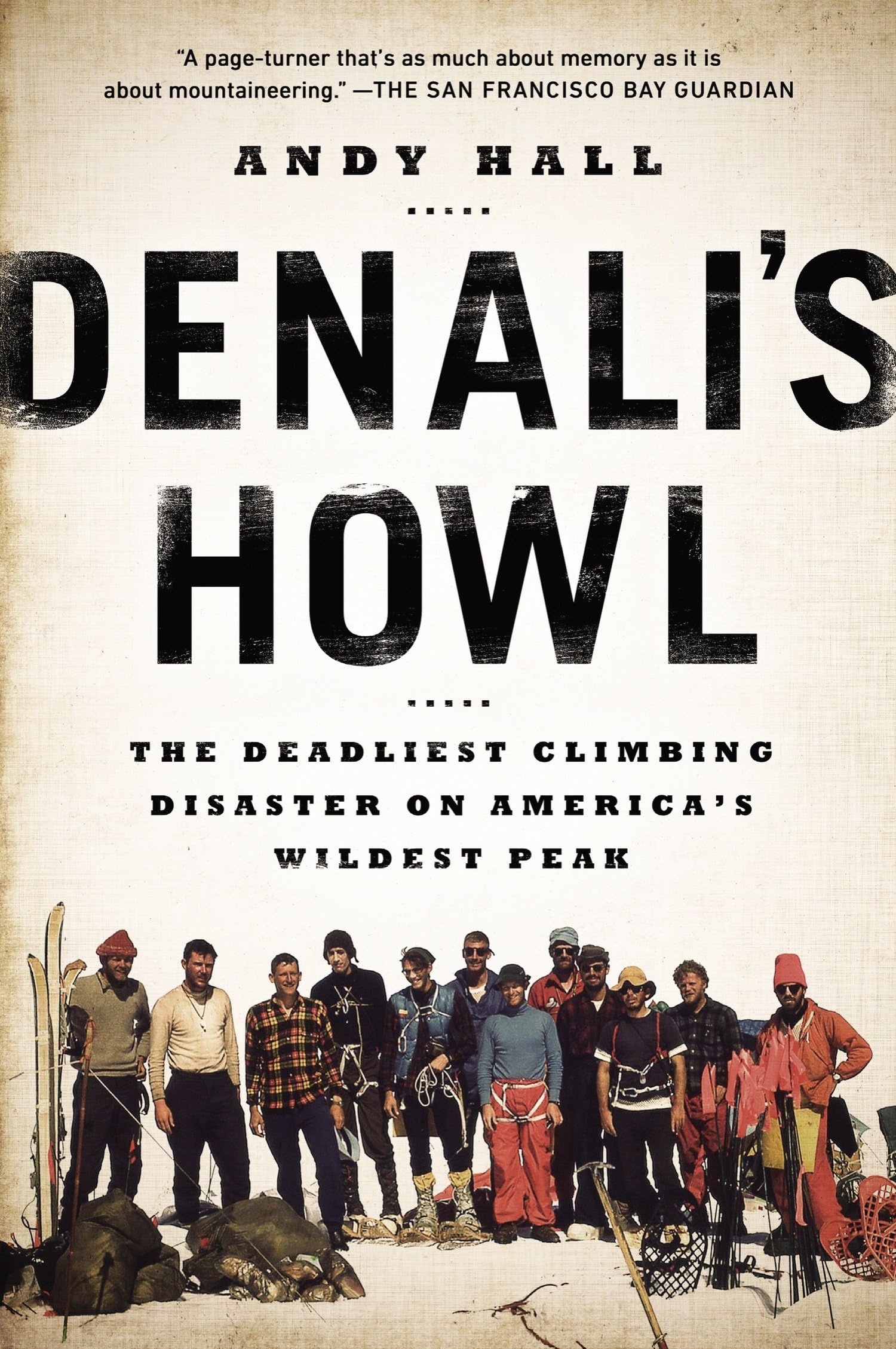

In the summer of 1967, twelve young men ascended Alaska’s Mount McKinley—known to the locals as Denali. Engulfed by a once-in-alifetime blizzard, only five made it back down. Andy Hall, a journalist and son of the park superintendent at the time, was living in the park when the tragedy occurred and spent years tracking down rescuers, survivors, lost documents, and recordings of radio communications. In Denali’s Howl, Hall reveals the full story of the expedition in a powerful retelling that will mesmerize the climbing community as well as anyone interested in mega-storms and man’s sometimes deadly drive to challenge the forces of nature. Praise for Denali’s Howl “In this straightforward, balanced account of the greatest mountaineering disaster in Alaskan history, Andy Hall allows the full tragedy of that episode to emerge. In resisting the facile urge to lay blame, his narrative captures with gripping immediacy the intersection of seemingly small human decisions with one of the most powerful storms ever to descend on Denali. As one who was climbing elsewhere in the Alaska Range at the time, I had long pondered just how the catastrophe came to pass. Thanks to Hall, I understand it better than ever before.” —David Roberts, author of The Mountain of My Fear and Alone on the Ice “A haunting, meticulously-researched account of twelve men’s encounter with the awesome fury of nature.” —Amanda Padoan, author of Buried in the Sky: The Extraordinary Story of the Sherpa Climbers on K’s Deadliest Day “Twelve men went up the slopes of North America's highest mountain in the summer of 1967. Only five made it back. The ill-fated Wilcox expedition to Denali finds an able chronicler in Andy Hall's gripping account of mountain majesty, mountain gloom, and human doom.” —Maurice Isserman, co-author of Fallen Giants: Himalayan Mountaineering from the Age of Empire to the Age of Extremes “One of those couldn’t-put-it-down books! This harrowing story of a more than 40-year-old mountaineering tragedy is raw and immediate as it marches relentlessly towards the final, devastating end.” —Bernadette McDonald, author of Freedom Climbers ANDY HALL grew up in the shadow of Denali. He is the former editor and publisher of Alaska magazine. He lives in Chugiak, Alaska. ***This excerpt is from an advance uncorrected proof*** Copyright © 2014 Andy Hall PROLOGUE A STRANGER IN THE WILDERNESS Joe Wilcox may not have been the first man to reach the summit of Denali, but on Saturday afternoon, July 15, 1967, he felt like it. A rare clear day reigned on the mountain outsiders call Mount McKinley. Wilcox and his three companions had savored it for the last few hours as they trudged upward on crusty, wind-carved snow. Atop the continent, Joe’s deep-set eyes swept over the Alaska Range— some of the tallest and most rugged peaks in North America— reduced to so many white waves of rock and ice lapping at the mountain’s base. But along with the grandeur there was an edge of tension. After twenty-seven days on the mountain, Wilcox knew that the window of good weather could close just as quickly as it had opened. The four men on the summit, along with the rest of their twelve-man team waiting for their turn just a couple of thousand feet below, had no time to waste. Wilcox had been on the mountain for nearly a month, and as he approached the summit the final steps seemed insignificant when compared to the tremendous effort the team had made to get there. The sweeping panorama instilled in him a sense of gratitude. He had worked hard, but that hard work did not guarantee success; he felt lucky. Two weather systems had been developing as Wilcox and his companions worked their way toward the summit: one to the northeast and one to the southwest. Rainclouds mustered over the Beaufort Sea, a stretch of ice-bound ocean that spans 1,200 unbroken miles between Alaska’s North Slope and the North Pole. In those days the sea was largely devoid of human traffic, save the occasional Eskimo* hunter. The low-pressure system spun to life and grew in intensity as it marched southwest carrying potent moisture-laden winds toward the Alaska Range. At the same time an equally strong high-pressure system developed over the Aleutian Islands, a windswept, treeless archipelago, known by mariners as the Cradle of Storms, southwest of Denali. The development and location of both weather systems at that time of year was unusual. These massive weather systems, separated by a thousand miles of forest, mountain, tundra, and taiga, were on a collision course, headed straight toward Joe Wilcox. On the summit at an elevation of 20,320 feet, Wilcox watched wind-whipped cirrus clouds high above him. These clouds marked the margins of the two massive weather systems as they began to brush against each other. In a matter of hours one of the most violent storms ever recorded on the mountain would engulf the peak and leave seven of Joe Wilcox’s twelve-man exped