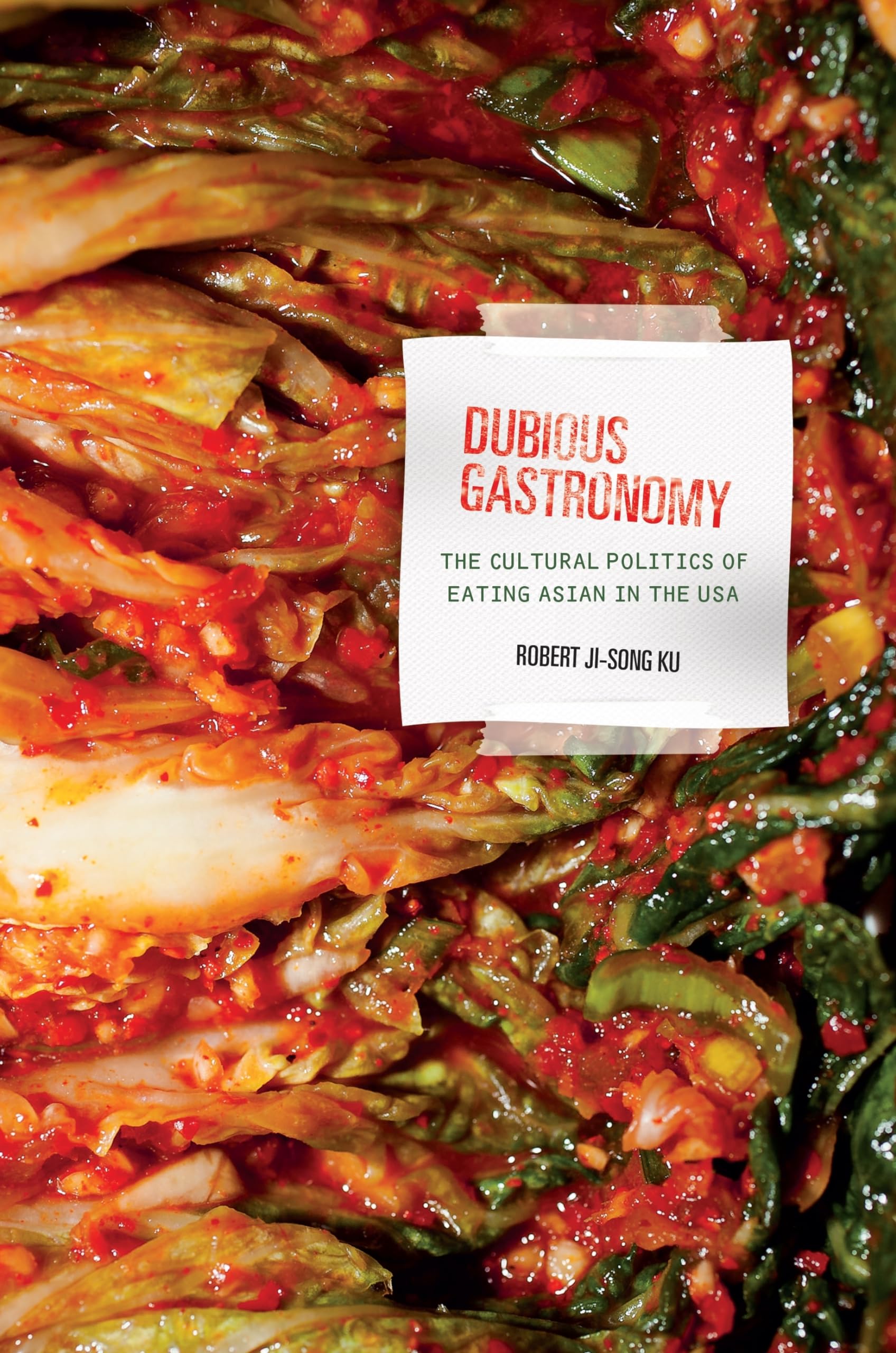

Dubious Gastronomy: The Cultural Politics of Eating Asian in the USA (Food in Asia and the Pacific)

$28.00

by Robert Ji-Song Ku

Shop Now

California roll, Chinese take-out, American-made kimchi, dogmeat, monosodium glutamate, SPAM―all are examples of what Robert Ji-Song Ku calls “dubious” foods. Strongly associated with Asian and Asian American gastronomy, they are commonly understood as ersatz, depraved, or simply bad. In Dubious Gastronomy, Ku contends that these foods share a spiritual fellowship with Asians in the United States in that the Asian presence, be it culinary or corporeal, is often considered watered-down, counterfeit, or debased manifestations of the “real thing.” The American expression of Asianness is defined as doubly inauthentic―as insufficiently Asian and unreliably American when measured against a largely ideological if not entirely political standard of authentic Asia and America. By exploring the other side of what is prescriptively understood as proper Asian gastronomy, Ku suggests that Asian cultural expressions occurring in places such as Los Angeles, Honolulu, New York City, and even Baton Rouge are no less critical to understanding the meaning of Asian food―and, by extension, Asian people―than culinary expressions that took place in Tokyo, Seoul, and Shanghai centuries ago. In critically considering the impure and hybridized with serious and often whimsical intent, Dubious Gastronomy argues that while the notion of cultural authenticity is troubled, troubling, and troublesome, the apocryphal is not necessarily a bad thing: The dubious can be and is often quite delicious. Dubious Gastronomy overlaps a number of disciplines, including American and Asian American studies, Asian diasporic studies, literary and cultural studies, and the burgeoning field of food studies. More importantly, however, the book fulfills the critical task of amalgamating these areas and putting them in conversation with one another. Written in an engaging and fluid style, it promises to appeal a wide audience of readers who seriously enjoys eating―and reading and thinking about―food. Ku’s book does not seek to simply prove that certain foods are inauthentic, disreputable, or artificial; instead, he queries how these malleable discursive categories are used to limit and channel the consumption of Asian and Asian American ethnicity. . . . Ku is at his best when he shows how often contemporary culinary discussions of Asian authenticity rely on and reinforce an orientalist East–West binary. Ku’s entry on dog meat, in particular, captures his trademark balance of sober research and challenging polemic. . . . Written in an accessible and entertaining voice, this book strikes a rhetorical balance, containing enough academic grist to push Asian American studies to further its critical engagement with the respective fields of food and postcolonial studies while providing a litany of anecdotes that would allow the book to sit comfortably on a coffee table next to Jennifer 8. Lee’s best seller, The Fortune Cookie Chronicles . ― American Quarterly The six chapters, each dedicated to a particular food, reveal long, complex histories that not only involve the circulation, production, and consumption but also unearth stories of migration and exclusion, revealing much about the complexities of definitional power over authenticity and the construction of multiple boundaries of Asian, American, and, most important, Asian Americanness. In doing so, Ku grapples with the complex role of food in the making and unmaking of borders and systems of order including national order, systems of belonging, order of the body, family belonging through the passing down of culinary knowledge, hierarchies of taste and palatability, and the very ordering of what is acceptable for human consumption. ― Journal of Asian American Studies Robert Ji-Song Ku is associate professor of Asian and Asian American studies at Binghamton University of the State University of New York. Introduction It is an altogether plausible tale: the Orient, once upon a time, was there, over yonder where the sun ascended to the heavens each day. Tasting the true flavors of the Orient, then, meant arduous journeys over mountains, oceans, and deserts. No longer. Today, the peoples of the Orient1 they Saracens or Celestials―reside by the multitudes in major metropolises and minor townships beyond the geographic Orient, including across the breadth of the United States. And, of course, found alongside these outlanders, no matter the country, region, or neighborhood, is an endless assortment of exotic delights, the culinary first and foremost. The Orient―or at least the gastronomic Orient―is now global, as diners far and wide need only walk down their own streets or make a quick phone call to make a meal of it. Not everyone is pleased, however. Culinary purists protest that Anthelme Brillat- Savarin’s old reliable adage, “Tell me what you eat and I’ll tell you what you are,” is now sadly obsolete, as anyone anywhere can at any time eat just about anything. As a consequence, to say that Chinese, In