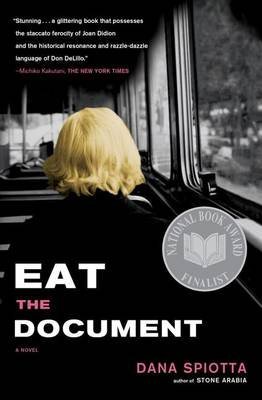

In the 1970s, Bobby Desoto and Mary Whittaker -- passionate, idealistic, and in love -- design a series of radical protests against the Vietnam War. When one action goes wrong, the course of their lives is forever changed. The two must erase their past, forge new identities, and never see each other again. Now it is the 1990s. Mary lives in the suburbs with her fifteen-year-old son, who spends hours immersed in the music of his mother's generation -- and she has no idea whether Bobby is alive or dead. An ambitious and powerful story about idealism, passion, and sacrifice, Eat the Document shifts between the underground movement of the 1970s and the echoes and consequences of that movement in the1990s. It is a riveting portrait of two eras and one of the most provocative and compelling novels of recent years. Spiotta's writing brims with energy and intelligence." -- The New York Times Book Review "Infused with subtle wit...singularly powerful and provocative...Spiotta has a wonderful ironic sensibility, juxtaposing '70s fervor with '90s expediency." -- The Boston Globe "Scintillating...Spiotta creates a mesmerizing portrait of radicalism's decline." -- The Seattle Times "Stunning...a glittering book that possesses the staccato ferocity of Joan Didion and the historical resonance and razzle-dazzle language of Don DeLillo." -- Michiko Kakutani, The New York Times By Heart It is easy for a life to become unblessed. Mary, in particular, understood this. Her mistakes -- and they were legion -- were not lost on her. She knew all about the undoing of a life: take away, first of all, your people. Your family. Your lover. That was the hardest part of it. Then put yourself somewhere unfamiliar, where (how did it go?) you are a complete unknown. Where you possess nothing. Okay, then -- this was the strangest part -- take away your history, every last bit of it. What else? She discovered, despite what people may imagine, having nothing to lose is a lot like having nothing. (But there was something to lose, even at this point, something huge to lose, and that was why this unknown, homeless state never resembled freedom.) The unnerving, surprisingly creepy and unpleasantly psychedelic part -- you lose your name. Mary finally sat on a bed in a motel room that very first night after she had taken a breathless train ride under darkening skies and through increasingly unfamiliar landscape. Despite her anxiety she still felt lulled by the tracks clicking at intervals beneath the train; an odd calm descended for whole minutes in a row until the train pulled into another station and she waited for someone to come over to her, finger-pointing, some unbending and unsmiling official. In between these moments of near calm and all the other moments, she practiced appearing normal. Only when she tried to move could you notice how shaky she was. That really undid her, her visible unsteadiness. She tried not to move. Five state borders, and then she was handing over the cash for the room -- anonymous, cell-like, quiet. She clutched her receipt in her hand, stared at it, September 15, 1972, and thought, This is the first day of it. Room Twelve, the first place of it. Even then, behind a chain lock in the middle of nowhere, she was double-checking doors and closing curtains. Showers were impossible; she half-expected the door of the bathroom to push in as she stood there unaware and naked. Instead of sleeping she lay on the covers, facing the door, ready to move. Showers and bed, nakedness and sleep -- she felt certain that was how it would happen, she could visualize it happening. She saw it in slow motion, she saw it silently, and then she saw it quickly, in double time, with crashes and splintered glass. Haven't you seen the photos of Fred Hampton's mattress? She certainly had seen the photos of Fred Hampton's mattress. They'd all seen them. She couldn't remember if the body was still in the bed in the photos, but she definitely remembered the bed itself: half stripped of sheets, the dinge stripe and seam of the mattress exposed and seeped with stains. All of it captured in the lurid black-and-white Weegee style that seemed to underline the blood-soak and the bedclothes in grabbed-at disarray. She imagined the bunching of sheets in the last seconds, perhaps to protect the unblessed person on the bed. Grabbed and bunched not against gunfire, of course, but against his terrible, final nakedness. "Cheryl," she said aloud. No, never. Orange soda. "Natalie." You had to say them aloud, get your mouth to shape the sound and push breath through it. Every name sounded queer when she did this. "Sylvia." A movie-star name, too fake sounding. Too unusual. People might actually hear it. Notice it, ask about it. "Agnes." Too old. "Mary," she said very quietly. But that was her real name, or her original name. She just needed to say it. She sat on the edge of the bed, atop a beige chenille bedspread with frays and loose threads, in he