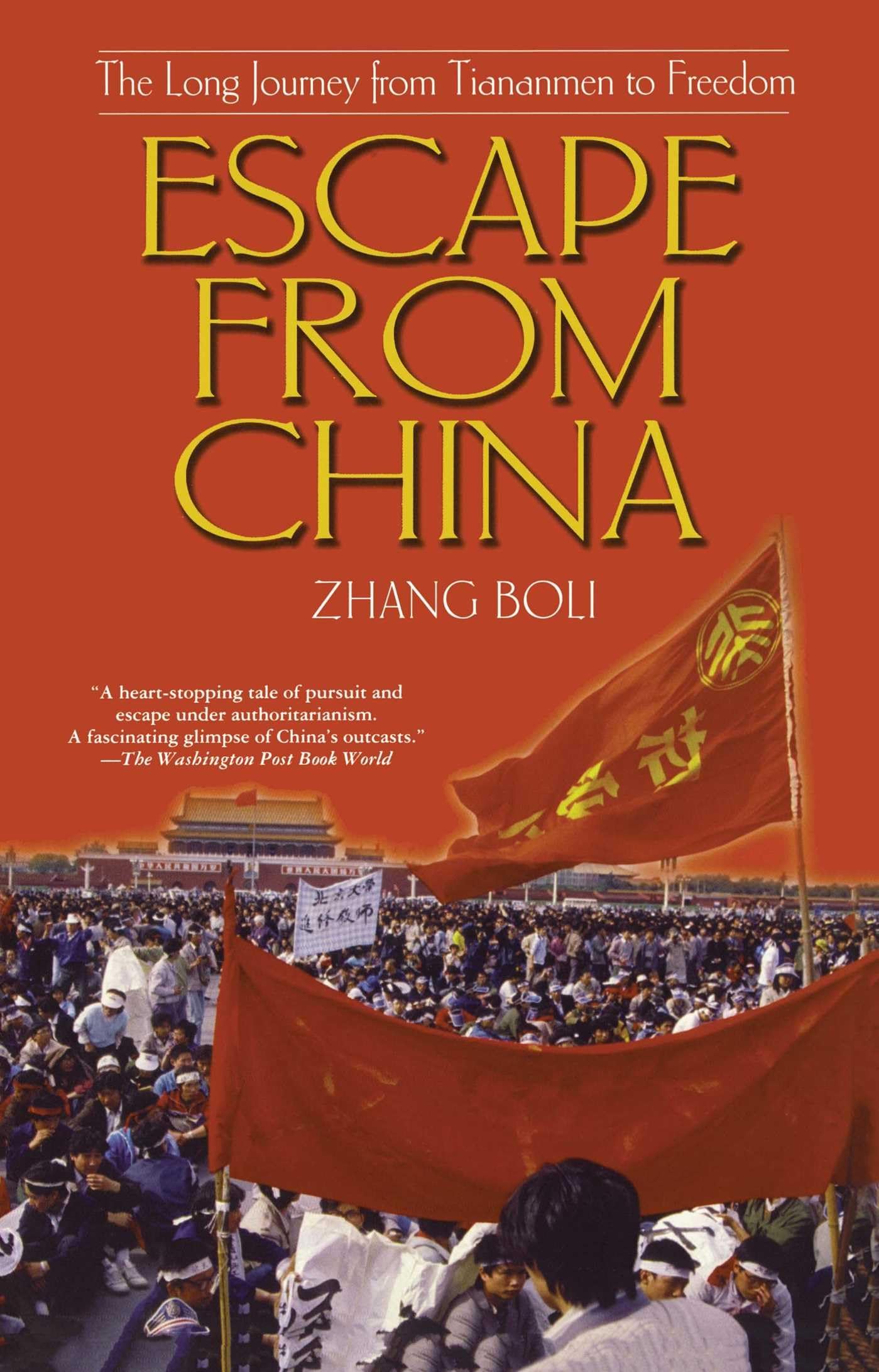

Who can forget the images, telecast worldwide, of brave Chinese students facing down tanks in Tiananmen Square as they took on their Communist government? After a two-week standoff in 1989, military forces suppressed the revolt, killing many students and issuing arrest warrants for top student leaders, including Zhang Boli. After two years as a fugitive, Zhang -- the only leader to elude capture -- knew that he must bid his beloved country, as well as his wife and baby daughter, farewell. Traveling across the frozen terrain of the former Soviet Union, where peasants rescued him, and through the deserted lands of China's precarious borders, Zhang had only his extraordinary will to propel him toward freedom. As told in Escape from China -- a work of great historical resonance -- his story will renew your faith in the human spirit. Andrew J. Nathan Professor of Political Science,Columbia University, co-editor of The Tiananmen Papers An instant classic....Zhang Boli's searing memories are brought to life with a wealth of concrete detail....He loses all, and gains all -- a classic human quest told in fresh form. Publishers Weekly Incisive, fast-paced....Zhang Boli presents his exploits modestly, but one is awed at every turn by his steely nerve andstreet savvy, and by the compassion that he liberally accords to humans, animals, and the land that gave him shelter. Perry Link Professor of East Asian Studies, Princeton University, author of China's New Rulers This book should be required reading for those who accept uncritically Chinese government claims to represent 'China.' The little people in this saga, generous and quiet, are China, too. Zhang Boli is now a pastor in Los Angeles, where he lives with his family. CHAPTER ONE: ESCAPE FROM BEIJING 1 June 4, 1989. In the predawn darkness we were forced to evacuate Tiananmen Square. Negotiations with the army were completed. The terms we agreed upon were simple: we should leave before daybreak. A peaceful conclusion to the occupation of this largest of public gathering places in all of China seemed within reach. Helmeted soldiers allowed us to pass through the narrow corridor at the southeast side of the square, all the while pointing their bayonets, as if we were prisoners of war. Army commanders had promised to give the demonstrators an opportunity to disperse. The process, time-consuming because the crowd was huge, seemed under way. "Fascist!" a female student cursed furiously. Immediately, several soldiers rushed at her and beat her down with the butts of their rifles. Her male comrades hurried to help her back into the march. And thus commenced the last phase of a major confrontation between nonviolent demonstrators led by university students and the armed forces of the People's Republic of China. On the one side, words: speeches, pamphlets, poems, petitions, the weapons of persuasion. On the other side, dictatorial power: guns, bullets, and tanks, the weapons of destruction. For more than fifty days, student idealists, naive but brave, had done all that they could to persuade their government by peaceful means to redress their grievances. A small group at first, their numbers had grown to the hundreds and then to the thousands. Now, amplified by ordinary citizens, they had grown to the tens of thousands. At times, more than a hundred thousand. A great dramatic spectacle, seen on television screens around the world, had reached its climax. And now an elite battalion of soldiers was moving to crush the Democracy Movement by brute force. As the day progressed, these soldiers, seemingly devoid of humanity, were to march against their own fellow citizens and employ lethal force. As soon as we began moving away from the square, the air was filled with the roar of tanks speeding ahead. I looked back and saw the statue of the Goddess of Democracy being torn down. Rows of tents, so geometrically ordered, were being crushed by the tanks' treads, the canvas sheets sometimes flying into the air like snowflakes driven by the wind. We marched and looked back through tears of anguish. The square we had occupied for fourteen days after the government had declared martial law was now an army's playground for the enjoyment of brutal games. In addition to our fears and rage, we felt a profound sense of humiliation. All of our noble words, our passionate deeds, our bravery in the face of enormous odds were being mocked; we had entered a realm of madness and were at the mercy of men -- the soldiers and their leaders -- who were utterly without humanity. Arriving at Liubu Avenue, we found that West Changan Street was still filled with the acrid nitric acid smoke of small arms and artillery fire. Here and there, military vehicles, buses, and tanks burned furiously. Destruction and horror everywhere. I turned on my pocket radio. The Central People's Radio was broadcasting an editorial of the Liberation Army Daily News, defining the nature of our democracy movemen