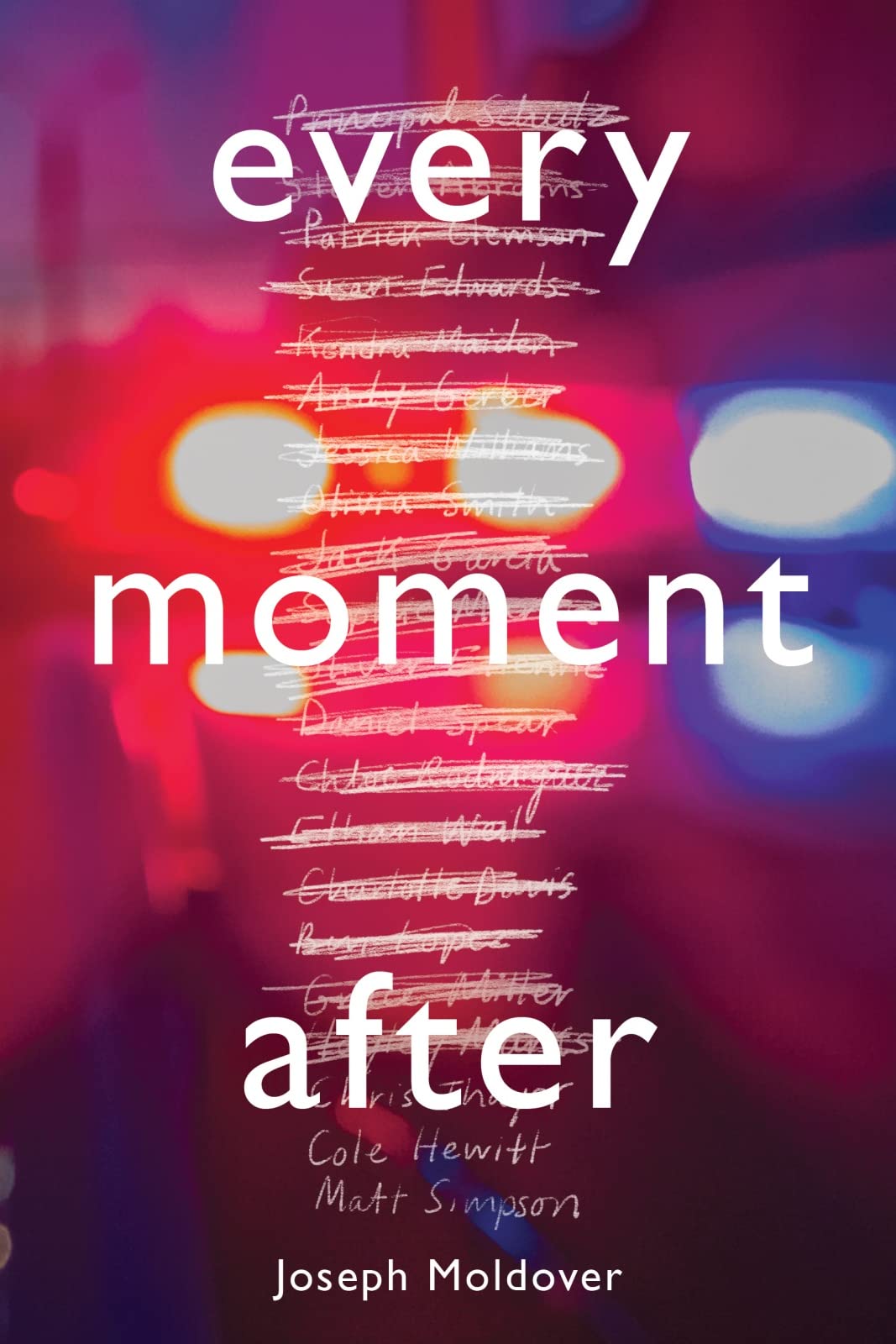

Every Moment After: A Young Adult Coming-of-Age Story of School Shooting Survivors and Friendship

$14.39

by Joseph Moldover

Shop Now

Best friends Matt and Cole grapple with their changing relationships during the summer after high school in this impactful, evocative story about growing up and moving on from a traumatic past. Surviving was just the beginning. Eleven years after a shooting rocked the small town of East Ridge, New Jersey and left eighteen first graders in their classroom dead, survivors and recent high school graduates Matt Simpson and Cole Hewitt are still navigating their guilt and trying to move beyond the shadow of their town's grief. Will Cole and Matt ever be able to truly leave the ghosts of East Ridge behind? Do they even want to? As they grapple with changing relationships, falling in love, and growing apart, these two friends must face the question of how to move on—and truly begin living. ? "[A] complex, sensitive exploration of referred emotional pain and the power of male friendships." — Bulletin of the Center for Children's Books , STARRED review "This debut powerfully captures the strong bonds of male friendship and the deep aftershocks of trauma. A solid pick for John Green fans." — Booklist "A sober, introspective coming-of-age tale." — Kirkus Joseph Moldover is a clinical psychologist who works with children, teenagers, and their families. He lives with his wife and their four children in Massachusetts. He has published a number of short stories, mostly under the name Joseph Sloan. Every Moment After is his debut novel. www. josephmoldover.com Twitter: @jmoldover One ' Cole ' People want to forget. No one would ever say it, but I think this town will be glad to see our class leave. They put up all the memorials you'd expect, but there was no need: we're living reminders. Year after year, walking the streets, sitting in the diner, popping up in marching band and on the baseball team. Teachers retired right before we got to them. Like we were a wave slowly sweeping from grade two to twelve, washing away all the old and tired ones, the ones who were sick of telling people they taught school in East Ridge, New Jersey, and getting that horrible look back. The ones who couldn't deal with staring out at our faces for a whole year. And now those who made it all the way to this afternoon have convinced themselves that they need to get through only a few more hours, as if they'll be able to forget us after we're gone. Even the weather knows the script today. Low gray clouds, black in the distance. A warm wind, midsixties. It will rain later, but it will hold off until after we've all gone home for quick parties with our parents before coming back to be bused off for Project Graduation. It will rain on empty chairs, eighteen of them still draped in black, and it will turn this field into mud. There are lots of people here now, though. Teachers, some parents, and other students who are helping to set up. Mom is toward the back, unfolding chairs from a cart. The principal and superintendent are going over paperwork together, probably making sure the superintendent knows how to pronounce all the last names. Lots of police, not surprisingly, some of them leaning against the back wall of the school and some in the parking lot, holding the press at bay. It's a few minutes past one; we're supposed to line up in half an hour. I'm trying to stay busy and starting to get frustrated with this uncooperative row of chairs. It's the tenth row back, left-hand side. I can get every chair to align with the one next to it, but somehow when I get to the center aisle, the line in its entirety is veering off on a slant. I start back to try again when I hear someone calling my name and see Mrs. Kennedy, my tenth-grade history teacher, waving to me from the front. I look around to see whether anyone's watching, push my sunglasses up the bridge of my nose, and make my way down to her. The black draperies aren't staying on in the wind. "Help me with this, Cole," she says. "I don't want poor Mrs. Maiden to have to.' The fabric is a weird sort of material, heavier than a bedsheet, kind of glossy. It's draped over the same flimsy chairs that we all have to sit in and it's taped in a few key spots so that it folds right, but the tape isn't holding. I study the third chair in from the aisle. If they were arranged alphabetically, whose seat would this be? Abrams, Clemson, Edwards. Susie Edwards. Unless Principal Schultz got the aisle, in which case everybody would be pushed in by one. Poor guy, having to show up for a high school graduation ceremony eleven years after his death. We should let him rest in peace. So let's just say that this one belongs to Susie. She was a funny little girl with pigtails. We played tag together. When we went out for recess that last winter, she used to ask me for help getting her snow boots on the right feet. I go in search of stronger tape so that her chair will look good. Mrs. Maiden is collating programs at the edge of the risers, and she pauses wh