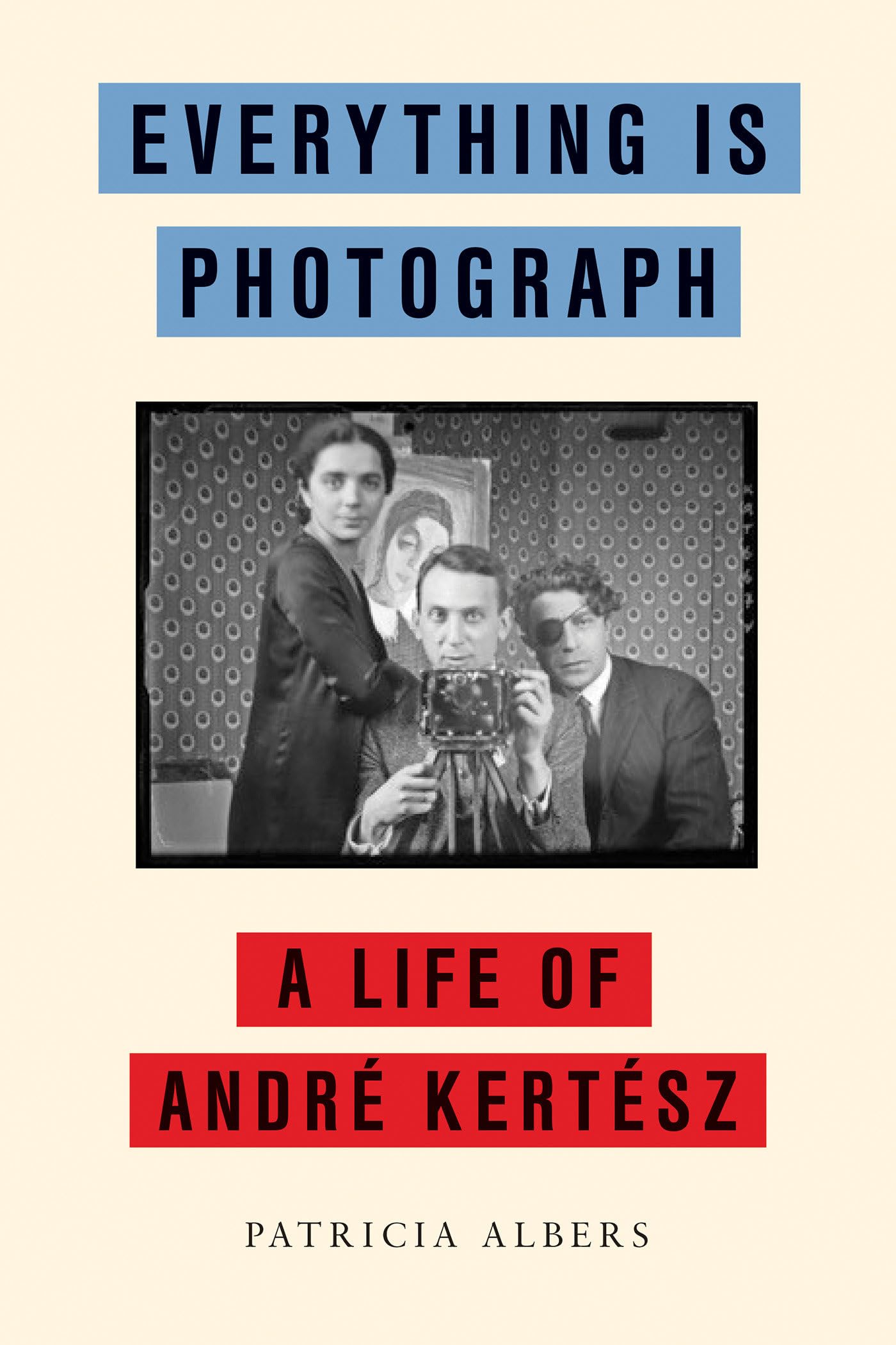

The first full biography of the innovative “father of modern photography” vividly depicts his life and works, from Hungary to France and America, across the 20th century. Born in Budapest in 1894, André Kertész soared to star status in Jazz Age Paris, tumbled into poverty and obscurity in wartime New York, slogged through 15 years shooting for House & Garden, then improbably reemerged into the spotlight with a 1964 retrospective at New York’s Museum of Modern Art. By the time of his death in 1985, he had exhibited around the world, taken more than 100,000 images, and steered the medium in new and vital directions: He was the first major photographer to embrace the Leica, the camera now mythically linked to street photography, and he pioneered subjective photojournalism, publishing what is arguably the world’s first great photo essay. Drawing on dozens of interviews, previous scholarship, and deep archival research, and interrogating the images themselves, Patricia Albers retrieves aspects of Kertész’s life that he and his pictures gloss over, among them the ordeals of trench warfare, the impact of the Holocaust, and the tale of his tangled romances. She takes Kertész from the Eastern front in World War I to the Paris of Piet Mondrian, Colette, Alexander Calder, and a lively central European diaspora. From Condé Nast’s postwar media empire to the “photo boom” of the 1970s. She revisits Kertész’s relationships with other photographers, among them his "frenemy" Brassaï and protégé Robert Capa. She breathes life into a gentle, generous, and unassuming man endowed with Old-World charm but also sputtering with grievance and rage and inclined to indulge in deception. Everything Is Photograph immerses readers in the heyday of a now lost version of photography. Formally vigorous, emotionally rich, and aesthetically charged, Kertész’s images speak of the medium as a tool for human connection, self-narration, self-invention, and inquiry about the world, even as they project its mysteries. “A comprehensive biography of the widely acclaimed photographer…A well-researched life of an iconoclast.” — Kirkus Reviews “[Kertész] is foundational to contemporary photography in the most fundamental of ways. Patricia Albers, a prominent California-based art historian, has released a new and quite definitive biography…Albers spends real time contextualizing Kertész’s artistic development…giving the reader a fuller sense of how his sensibility was shaped and reshaped across continents…insightful.” — F-Stop Magazine Praise for Joan Mitchell : “Patricia Albers has written a book about Mitchell that I cannot imagine will ever be improved upon, so graceful and incisive is her account of the artist’s hellbent life and lyric art.” — New York Times “Like Mitchell’s vast canvases, Albers’s impressive book ought to be experienced in the morning, ‘for it can animate the entire day.’” — The New Yorker Patricia Albers is a California-based writer, editor, and art historian. She is the author of Joan Mitchell, Lady Painter: A Life , the acclaimed first biography of the abstract painter. Her previous books include Shadows, Fire, Snow: The Life of Tina Modotti and Tina Modotti and the Mexican Renaissance . Albers’s essays, art reviews, and features have appeared in numerous museum catalogs and publications. Introduction Self-Portrait, Paris is conjured from practically nothing: parts of a door and a wall, the shadow of the photographer gripping the tripod attached to his camera. A shadow within a shadow, actually, because of the two light sources, one yielding an ordinary profile, the other, an oafish umbra. Tucked into the picture’s upper-left corner is the only material object: the box lock on the door. The lock resembles a camera, with its covered keyhole as the lens, complete with focusing ring. What’s behind that keyhole? The image offers no clues. Self-Portrait, Paris is a scene from a shadow play. A meditation on photography, seeing, and self. A nod to the negative-positive process, described by one of its inventors as “the art of fixing a shadow.” Behind the real camera that winter night in 1927 stood a tall, scrawny, thirty-two-year-old transplant to Paris. André Kertész had arrived from his native Hungary sixteen months earlier on a train ticket purchased with a loan from a cousin. Paris represented his best hope to establish himself as a photographer. Whatever that meant. Photographers made their living from studio portraiture, newspaper work, or commercial jobs like supplying pictures for postcards. All that bored André. He wanted a more direct contact with life. But he did need to eat. He spoke little French, nor did he believe he could learn. He had no savings. Often he skipped meals or made do with bread, butter, and milk, tallying his purchases each night before bed. A baguette cost the equivalent of a nickel, a bottle of milk and cube of butter, fourteen cents. His eyes were irritated. He couldn’t sleep