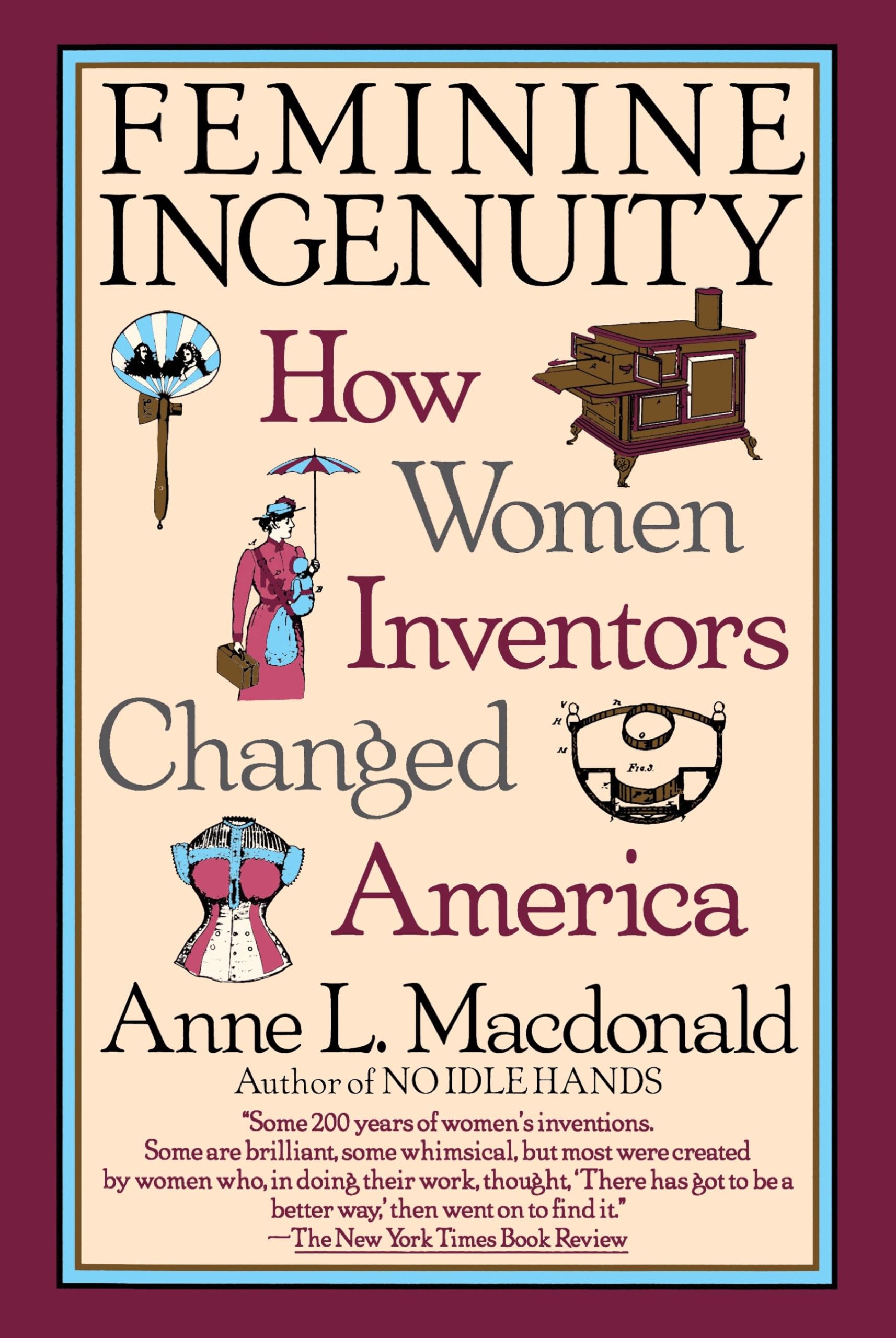

"Written with clarity and a lively eye both for detail and for the progress of feminism in the United States." SAN FRANCISCO CHRONICLE In this fascinating study of American women inventors, historian Anne Macdonald shows how creative, resourceful, and entrepreneurial women helped to shatter the ancient stereotypes of mechanically inept womanhood. In presenting their stories, Anne Macdonald's thorough research in patent archives and her engaging use of period magazine, journals, lectures, records from major fairs and expositions, and interviews, have made her book nothing less than an overall history of the women's movement in America. n with clarity and a lively eye both for detail and for the progress of feminism in the United States." SAN FRANCISCO CHRONICLE In this fascinating study of American women inventors, historian Anne Macdonald shows how creative, resourceful, and entrepreneurial women helped to shatter the ancient stereotypes of mechanically inept womanhood. In presenting their stories, Anne Macdonald's thorough research in patent archives and her engaging use of period magazine, journals, lectures, records from major fairs and expositions, and interviews, have made her book nothing less than an overall history of the women's movement in America. "What useful things have American women conceived of and developed that have contributed to the progress of technology, science, and engineering?" Raise that question, even among educated feminists of the 1990s, and you are likely to be met with a fumbling for names. Raise it among the skeptics of women's creative talents and they will reply "Where, after all, is the historical record?" "In the Patent Office", replies historian Anne L. Macdonald, author of Feminine Ingenuity. In her engaging and meticulously researched history of American women inventors, she presents not only the official evidence of women's remarkable achievements contained in two centuries' worth of Patent Office archives, but also a wealth of material she has discovered in unofficial contemporary accounts of women's inventions: magazines, journals, lectures, major fairs and expositions, and the manuscripts of several important inventors. Feminine Ingenuity celebrates the achievements of women inventors from Mary Kies, whose 1809 patent for a method of weaving straw was the first issued to a woman, to Gertrude Elion, the Nobel Prize Laureate whose anticancer drugs led to her 1991 election as the first woman in the Inventors Hall of Fame. It is not, however, a litany of accomplishments of previously unsung individual women, for Macdonald doesn't ignore the downside of women's struggle. Society, with its relentless assignment of females to the domestic sphere, discouraged mechanically talented girls by barring them from the kind of technical education it lavished upon their brothers. It took the Civil War and the consequent absence of their men to force these alumnae of required cooking and sewing classes to learn notonly to operate farm machinery but to invent major improvements to it. By presenting women inventors against such a historical backdrop, Macdonald keys their experiences to the larger themes of women's changing economic, political, and social position. This makes Feminine Ingenuity a thought-provoking account of a significant and previously neglected aspect of the history of women. Anne L. Macdonald was for fifteen years chairperson of the history department of the National Cathedral School in Washington, D.C. She was the author of No Idle Hands: The Social History of American Knitting and Feminine Ingenuity: Women and Invention in America . She died in 2016. INTRODUCTION Whenever I talk about having written a book on American women inventors, someone always pipes up, “Well, what did women invent? Anything really important?” Though I console myself that no one seriously questions women’s ability to invent, I can count on one hand those who know the name of even one American woman who actually did. When I explain that I have narrowed my subject to women who actually received patents for their inventions, my audience is further nonplussed. “Is this a very recent development, women getting patents?” asked one. A friend who has practiced patent law for four decades said he has never represented a female inventor. Others ask me to name a few patentees, and I am tempted to roll out the big names, whether their inventions broke important ground or not. A trio of actresses might do: Take Hedy Lamar, whose patent was for a secret wartime communications system; or May Robson, who invented a false leg for stage use; or Lillian Russell, who received a patent for a clever wardrobe trunk that could double as a bureau when she was on tour. Even one of Rudolph Valentino’s wives, Winifred Hudnut Gugliemi—professionally known as Natacha Rambova—had a patent (for a coverlet and doll). I must admit that before I undertook this project I, too, knew the names of only a few women pat