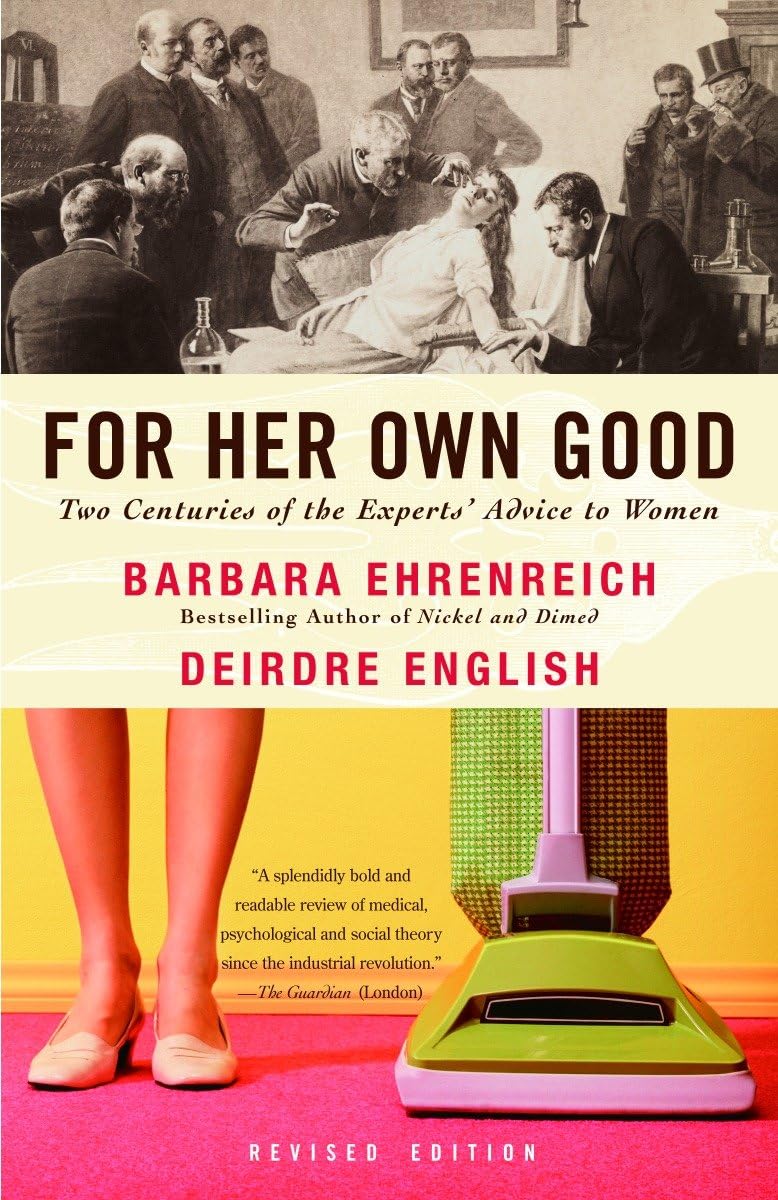

For Her Own Good: Two Centuries of the Experts Advice to Women

$17.09

by Barbara Ehrenreich

Shop Now

From the bestselling author of Nickel and Dimed and a former editor in chief Mother Jones , this women's history classic brilliantly uncovers the constraints imposed on women in the name of science. Since the nineteenth century, professionals have been invoking scientific expertise to prescribe what women should do for their own good. Among the experts’ diagnoses and remedies: menstruation was an illness requiring seclusion; pregnancy, a disabling condition; and higher education, a threat to long-term health of the uterus. From clitoridectomies to tame women’s behavior in the nineteenth century to the censure of a generation of mothers as castrators in the 1950s, doctors have not hesitated to intervene in women’s sexual, emotional, and maternal lives. Even domesticity, the most popular prescription for a safe environment for women, spawned legions of “scientific” experts. Barbara Ehrenreich and Deirdre English has never lost faith in science itself, but insist that we hold those who interpret it to higher standards. Women are entering the medical and scientific professions in greater numbers but as recent research shows, experts continue to use pseudoscience to tell women how to live. For Her Own Good provides today’s readers with an indispensable dose of informed skepticism. “A splendidly bold and readable review of medical, psychological and social theory since the industrial revolution.”— The Guardian (London) "A landmark work: It changes everything one believed before about doctors, scientists, and all other kinds of patriarchal experts. The most important work on women since The Feminine Mystique ."--Claudia Dreifus, author of Seizing Our Bodies, The Politics of Women's Health Care " For Her Own Good gives us a perspective on female history, the history of American medicine and psychology, and the history of childhood, unlike any we have had. I have read it with mounting intellectual excitement, underlining, marking pages, arguing form start to finish with its authors in my head. It is humanly and theoretically fascinating, written with clarity, wit, and verve and with a deep concern for the future."--Adrienne Rich " For Her Own Good . . . uses rationality informed by moral insight to meet the 'experts' head-on."— The Boston Globe A provocative new perspective on female history, the history of American medicine and psychology, and the history of child-rearing unlike any other. A provocative new perspective on female history, the history of American medicine and psychology, and the history of child-rearing unlike any other. Barbara Ehrenreich has written and lectured widely on subjects related to health care and women's issues. She has contributed articles to Time , Harper's , and T he New York Times Book Review , among others. She is the bestselling author of nearly 20 books including Nickel and Dimed and Bait and Switch . Deirdre English has written, taught, and edited work on a wide array of subjects related to investigative reporting, cultural politics, and public policy. She has contributed to Mother Jones , The Nation , and The New York Times Book Review , among other publications, and to public radio and television. One In the Ruins of Patriarchy "If you would get up and do something you would feel better," said my mother. I rose drearily, and essayed to brush up the floor a little, with a dustpan and small whiskbroom, but soon dropped those implements exhausted, and wept again in helpless shame. I, the ceaselessly industrious, could do no work of any kind. I was so weak that the knife and fork sank from my hands-too tired to eat. I could not read nor write nor paint nor sew nor talk nor listen to talking, nor anything. I lay on the lounge and wept all day. The tears ran down into my ears on either side. I went to bed crying, woke in the night crying, sat on the edge of the bed in the morning and cried-from sheer continuous pain. Not physical, the doctors examined me and found nothing the matter.1 It was 1885 and Charlotte Perkins Stetson had just given birth to a daughter, Katherine. "Of all angelic babies that darling was the best, a heavenly baby." And yet young Mrs. Stetson wept and wept, and when she nursed her baby "the tears ran down on my breast. . . ." The doctors told her she had "nervous prostration." To her it felt like "a sort of gray fog [had] drifted across my mind, a cloud that grew and darkened." The fog never entirely lifted from the life of Charlotte Perkins Stetson (later Gilman). Years later, in the midst of an active career as a feminist writer and lecturer, she would find herself overcome by the same lassitude, incapable of making the smallest decision, mentally numb. Paralysis struck Charlotte Perkins Gilman when she was only twenty-five years old, energetic and intelligent, a woman who seemed to have her life open before her. It hit young Jane Addams-the famous social reformer-at the same time of life. Addams was affluent, wel