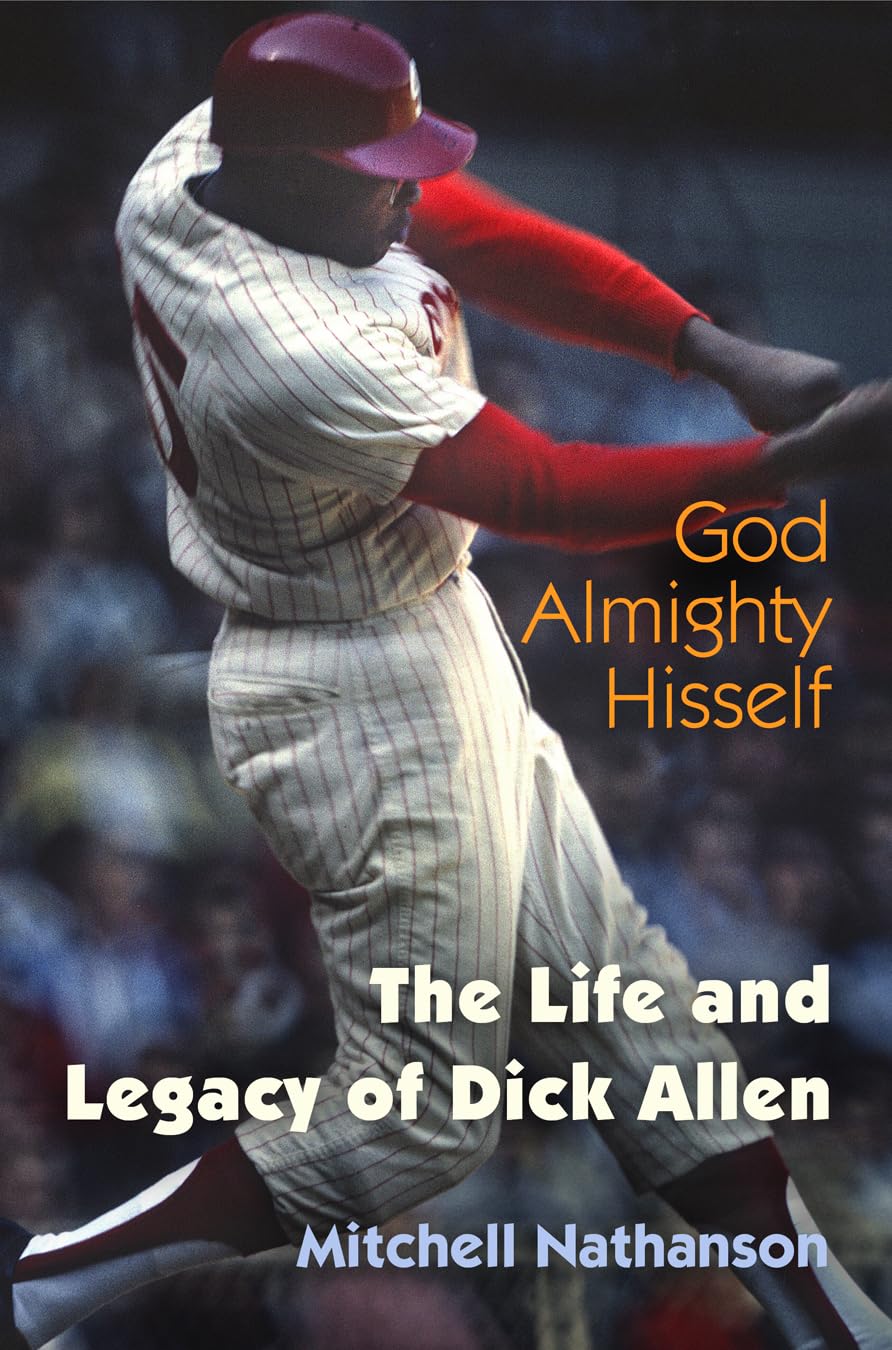

When the Philadelphia Phillies signed Dick Allen in 1960, fans of the franchise envisioned bearing witness to feats never before accomplished by a Phillies player. A half-century later, they're still trying to make sense of what they saw. Carrying to the plate baseball's heaviest and loudest bat as well as the burden of being the club's first African American superstar, Allen found both hits and controversy with ease and regularity as he established himself as the premier individualist in a game that prided itself on conformity. As one of his managers observed, "I believe God Almighty hisself would have trouble handling Richie Allen." A brutal pregame fight with teammate Frank Thomas, a dogged determination to be compensated on par with the game's elite, an insistence on living life on his own terms and not management's: what did it all mean? Journalists and fans alike took sides with ferocity, and they take sides still. Despite talent that earned him Rookie of the Year and MVP honors as well as a reputation as one of his era's most feared power hitters, many remember Allen as one of the game's most destructive and divisive forces, while supporters insist that he is the best player not in the Hall of Fame. God Almighty Hisself: The Life and Legacy of Dick Allen explains why. Mitchell Nathanson presents Allen's life against the backdrop of organized baseball's continuing desegregation process. Drawing out the larger generational and business shifts in the game, he shows how Allen's career exposed not only the racial double standard that had become entrenched in the wake of the game's integration a generation earlier but also the forces that were bent on preserving the status quo. In the process, God Almighty Hisself unveils the strange and maddening career of a man who somehow managed to fulfill and frustrate expectations all at once. "I've been writing for several years that there was a very good book to be written about Dick Allen and why he isn't in the Baseball Hall of Fame. Now that book has been written. God Almighty Hisself: The Life and Legacy of Dick Allen by Mitchell J. Nathanson, a law professor at Villanova University, is, in my opinion, one of the half-dozen or so best baseball books published so far this century." ― Allen Barra in Truthdig "An excellent and unflinching examination of the tragedy that ensued when the first baseball superstar insistent on full racial equality joined one of the last baseball teams to integrate." ― Keith Olbermann "Nathanson gives us an unapologetic view of the collision between the ultra-talented and complex Dick Allen and Major League Baseball's tumultuous postintegration era. He adeptly illuminates that Allen was a driver, passenger, and innocent bystander, all in one conflicted soul." ― Doug Glanville "I loved Dick Allen for reasons that I could never totally explain. Maybe it was his big bat and electric presence at the plate; maybe it was his individualism and outspokenness; maybe it was that image of him using his cleats to dig BOO into the dirt near the first base bag in Philly. Now, with Mitchell Nathanson's penetrating and revelatory book, I appreciate the full dimensions of this mysterious baseball rebel." ― David Maraniss, author of Clemente: The Passion and Grace of Baseball's Last Hero Mitchell Nathanson is Professor of Law at Villanova University School of Law. He is author of A People's History of Baseball and coauthor of Understanding Baseball: A Textbook. Prologue Baseball's Way "I wouldn't say that I hate Whitey, but deep down in my heart, I just can't stand Whitey's ways, man." Dick Allen, in repose, at last, with a reporter of all people, spoke freely and held nothing back. A confluence of factors unburdened him for what seemed like the first time in years, maybe the first time ever, or at least since anybody outside of Wampum, Pennsylvania, had become aware of the bespectacled Superman with the seemingly never-ending litany of first names (Dick? Rich? Richie? Sleepy?). He was finally rid of both Philadelphia and the Phillies after six-plus years of torment on both sides of the equation, having settled tranquilly (although not wholly without incident) in St. Louis with the Cardinals, an organization known as much for its acceptance of its black ballplayers as its on-field success. He was now just one of the guys on a team replete with future Hall of Famers, such as Lou Brock, Bob Gibson, and Steve Carlton, and no longer the athletic fulcrum of an entire city. And he was rapping with a member of the black media for a change—speaking with someone who perhaps was more likely to understand who he was and where had been—someone who knew what it took to have to deal with those who assumed that the issue of equality had been solved years before with the abolition of "separate but equal" and the segregated lunch counters and water fountains that went with it. For a moment at least, Dick Allen was at peace. The Ebony reporter tr