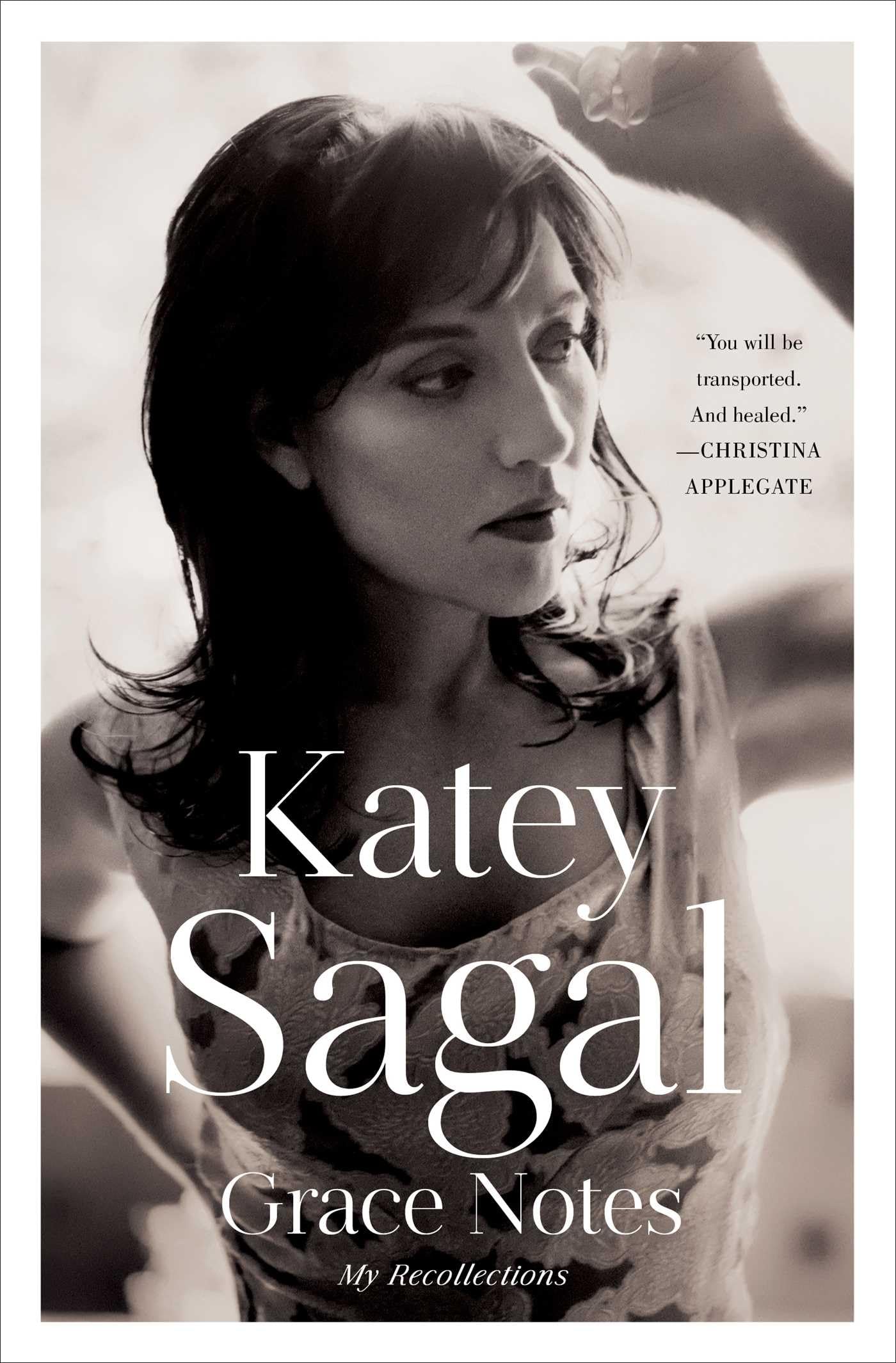

Award-winning beloved actress and talented singer/songwriter Katey Sagal crafts an evocative and gripping memoir told in essays—perfect for fans of Patti Smith’s M Train and Mary-Louise Parker’s Dear Mr. You. In Grace Notes , Katey Sagal chronicles the rollercoaster ride of her life in this series of gorgeously wrought vignettes, resulting in a memoir unlike any other Hollywood memoir you’ve read before. She takes you through the highs and lows of her life, from the tragic deaths of her parents to her long years in the Los Angeles rock scene, from being diagnosed with cancer at the age of twenty-eight to getting her big break on the fledgling FOX network as the wise-cracking Peggy Bundy on the beloved sitcom Married…with Children . Sparse and poetic, Grace Notes is an emotionally riveting tale of struggle and success, both professional and personal: Sagal’s battle with sobriety; the still birth of her first daughter, Ruby; the challenges of maintaining a marriage with her second husband as he struggled with his own addiction; motherhood; the experience of having her third daughter at age fifty-two with the help of a surrogate; and her lifelong passion for music. Intimate, candid, and offering an inside look at the entertainment industry, Grace Notes offers unprecedented access to the previously unknown life of a woman whom audiences have loved for over thirty years. A versatile and award-winning actress, Katey Sagal is also a talented songwriter and singer. With over thirty years in show business, Katey has gained a legion of loyal fans who have followed her from Married…with Children , 8 Simple Rules , Futurama , to Sons of Anarchy , for which she won a Golden Globe. She currently resides in Los Angeles with her husband, three children, and two dogs. Follow her on Twitter @KateySagal. Grace Notes The Singing Sweetheart of Cherokee County When I was ten, my mother taught me to play the guitar. We were living in the Westwood section of Los Angeles at the time. Dark and cavernous, the house seemed to me an enormous Spanish hacienda. (I went back years later, and it was more like a casita.) Mom and I sat in the living room, the dark wooden floors and rich red tiles providing the effect of an echo chamber. My mom, as always, was dressed in her simple way, with her hair cut in a short, unstuffy style that I understood later was meant to avoid adding complications to her life. “Darling girl!” She called me to her. “Let me show you. This is what I did at your age.” I sat on her lap, the guitar in mine, with her arms draped around me, and we picked and strummed in tandem, like one person. My hands hurt as I stretched and pressed my fingers into the strings. She rested her hands, bird-like and delicate, on top of mine and helped to mold my fingers into chord formations with one hand while strumming with the other. If I concentrate, I can still feel her small hands touching me. I was so much bigger than her, even as a little kid. She was happy then and suntanned, memorable because it was rare that she had color. She stayed inside so much of the time. “Down in the Valley” was the first song I learned. A traditional folk ballad my mom played every time she picked up her guitar. We sang loudly. My hands wrapped around the wide neck of Mom’s maple-colored Martin. Her nylon string acoustic guitar, the one she was given by Burl Ives. I never really knew why or how she got his guitar; that’s one of the heartbreaks of having dead parents: no one to fill in the blanks. “Down in the valley, valley so low, hang your head over, hear the wind blow . . .” Kent cigarettes, butts and burning, in an ashtray nearby. The smell of slept-in clothes, dirty hair, and tobacco—the smells of my mom—filling the space along with the low, rich tones of her voice. A deep alto by this time in her life, she still sang with the faint twang of the yodeler she was in her younger years. Long ago, when my mother was eleven years old, she had her own fifteen-minute daily radio show out of Gaffney, South Carolina. She was known as “the Singing Sweetheart of Cherokee County.” I imagine Mom at eleven to have been hopeful and enthusiastic, full of promise and invigorated by life’s possibilities. But this Mom—the Mom at age thirty-five whom I sat with in our living room—her, not so much. This was years after the radio show. Much had happened in her life—and not happened. By the time I was old enough to know my mom, she’d moved far beyond “the Singing Sweetheart of Cherokee County” to a life of darkened rooms and hushed hallways, the house’s forced stillness when she had taken to her bed. The official diagnosis was heart disease, but I’ve always thought she had a broken heart. Mom had started working young and would continue to do so in many different forms until she married. From the radio show at eleven in Gaffney, she was discovered by NBC Radio and sent to New York to continue her show. The family lore goes that m