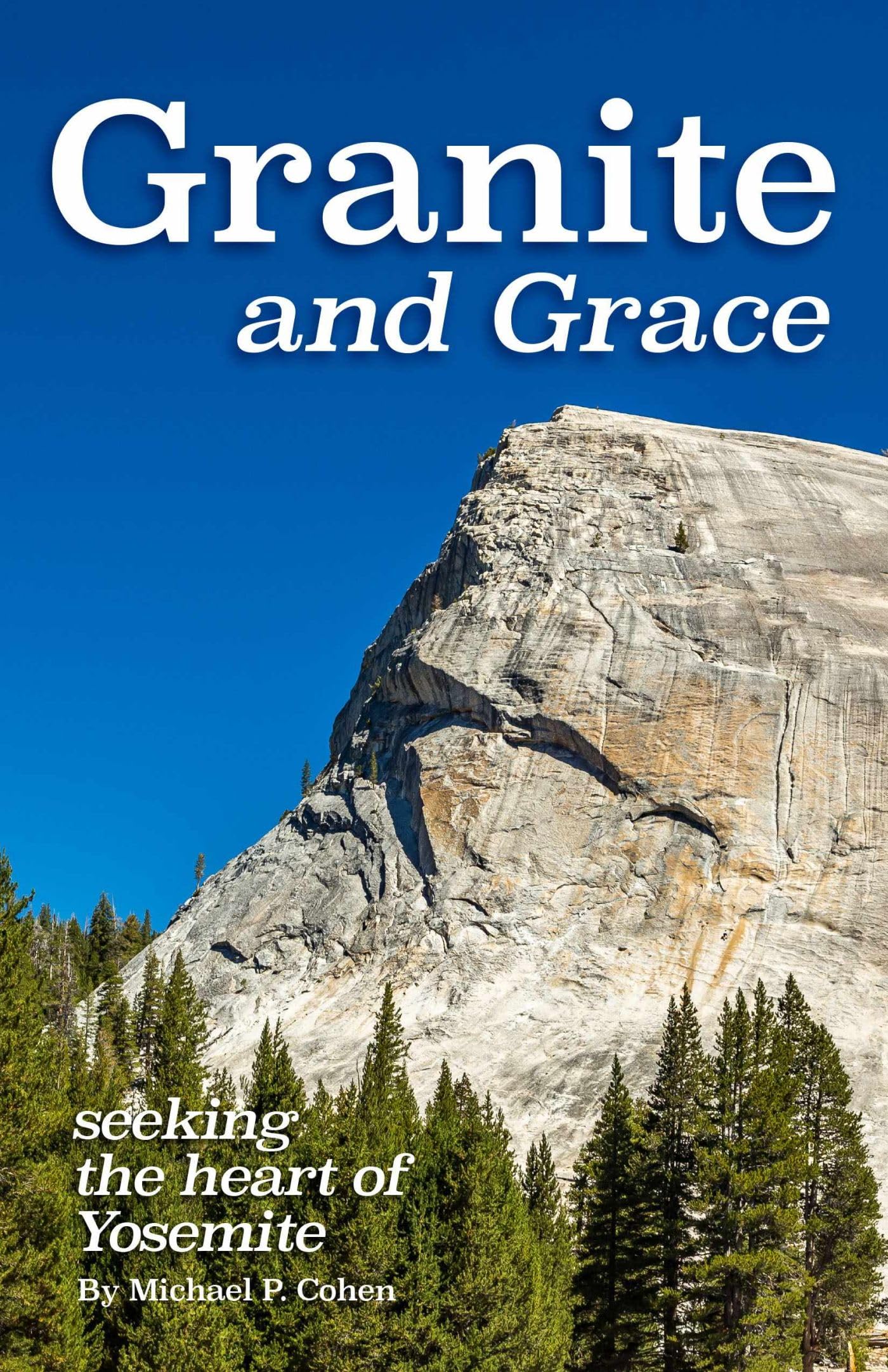

In Granite and Grace Michael Cohen reflects on a lifetime of climbing, walking, and pondering the granite in Yosemite National Park at Tuolumne Meadows. This high-country region of Yosemite is dominated by a young, beautifully glaciated geological formation known as the Tuolumne Intrusive Suite. It does not include familiar Yosemite icons like Half Dome, yet geologists describe this granitic realm at over 8,000 feet as “an iconic American landscape.” Drawing together the humanistic and scientific significance of the wild landscapes he traverses, Michael uncovers relationships between people and places and meaning and substance, rendering this text part memoir—but also considerably more. On-the-rock encounters by hand and foot open up a dialogue between the heart of a philosopher and the mind of a geologist. Michael adds a literary softness to this hard landscape, blending excursions with exposition and literature with science. It is through his graceful representations that the geological becomes metaphorical, while the science turns mythological. This high country, where in 1889 John Muir and Robert Underwood Johnson planned what would become Yosemite National Park, is significant for cultural as well as natural reasons. Discoursing on everything from Camus’s “Myths of Sisyphus” to the poems of Gary Snyder, Michael adds depth to an already splendorous landscape. Premier early geologists, such as François Matthes, shaped the language of Yosemite’s landscape. Even though Yosemite has changed over half a century, the rock has not. As Michael explores the beauty and grace of his familiar towering vistas, he demonstrates why, of the many aspects of the world to which one might get attached, the most secure is granite. “Cohen melds his lifetime of serious literary reading with a lifetime of wandering on and among the granite of Tuolumne Meadows. To these exalted preoccupations add the soul of poet and the intellectual curiosity of a geologist. The result is not only intimate, but, as the title promises, full of grace.” -- David Stevenson, author of Warnings Against Myself: Meditations on a Life in Climbing Michael P. Cohen is an award-winning author of several books including Tree Lines and A Garden of Bristlecones . Cohen, a rock climber and mountaineer, is a pioneer of first ascents in the Sierra Nevada and has been a professional mountain guide. He splits his time between Reno, Nevada, and June Lake, California. He first visited Tuolumne Meadows in 1955. Introduction This modest set of essays explores our nearly lifelong experiment to experience and respond to the granite of a region called Tuolumne Meadows in Yosemite National Park (figure 1). Other than remarkable granite forms, many aspects of this place have attracted us over the years, not the least of which is the community of people who are also drawn to the region. But we came and lived here as much as we could to expose ourselves to granite, to feel and explore it, and to explore ourselves. Tuolumne Meadows provided a place for us to think and feel. This book tests our nonscientific experiments. While walking on trails in national parks, it is not surprising to overhear people who spend most of their time talking not about where they are, but about concerns from where they come, as if they cannot afford to pay full attention to the present rock on which they tread. When Valerie and I desire to persuade these hikers to change we are immediately faced by a strange paradox. We have only ourselves as solitary exemplars and must speak about ourselves, not only where we are. As Henry David Thoreau so famously wrote, “I should not talk so much about myself if there were anybody else whom I knew as well.”1 This book intends to avoid the so--called “wilderness controversy” despite the prominence of solitary experience here, which would seem to reveal traditional wilderness predilections.2 The institutional construction of the Wilderness Act of 1964 embedded within it a concept of solitude, defining wilderness areas in part as affording “outstanding opportunities for solitude or a primitive and unconfined type of recreation.”3 Nevertheless, the concept of solitude is much older and more nuanced than the American conservation movement’s version of it, and I refer to that more venerable concept when I speak of solitude. When “a person longs for solitude and at the same time is fearful of it,” the Hungarian translator, critic, and art critic F. László Földényi argues, such a person may become a prisoner of that longing.4 Solitude might also make him free. How to separate a desire for solitude from ideological issues, a desire for privacy, or even a predilection toward melancholy? Földényi insists that solitude, silence, and melancholy are wrapped inextricably around each other: “A melancholic wishes, first and foremost, to escape from himself , but he can find no crack in the homogeneous, overarching culture, and resignation grows in him,