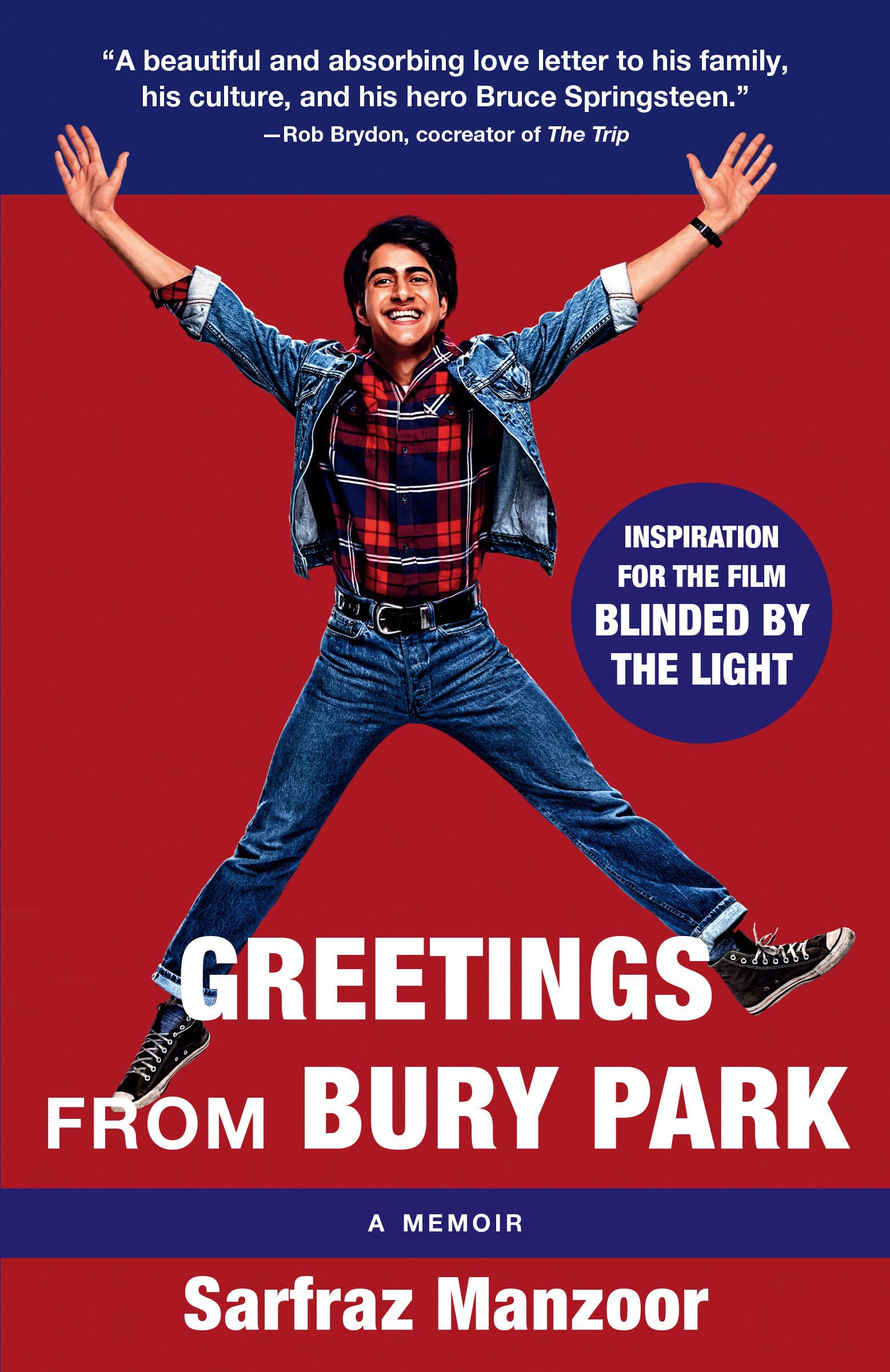

Greetings from Bury Park (Blinded by the Light Movie Tie-In) (Vintage Departures)

$13.66

by Sarfraz Manzoor

Shop Now

NOW A MAJOR MOTION PICTURE. A charming memoir about the impact of Bruce Springsteen's music on a Pakistani boy growing up in 1970s Britain. Sarfraz Manzoor was two years old when, in 1974, he emigrated from Pakistan to Britain with his mother, brother, and sister. He spent his teenage years in a constant battle, trying to reconcile being both British and Muslim, trying to fit in at school and at home. But when his best friend introduced him to the music of Bruce Springsteen at age sixteen, his life changed completely. From the moment Manzoor heard the opening lines to "The River," Springsteen became his personal muse, a lens through which he was able to view the rest of his life. Both a tribute to The Boss and a story of personal discovery, Blinded by the Light (originally published as Greetings from Bury Park ) is a warm, irreverent, and exceptionally perceptive memoir about how music transcends religion and race. Featuring a new afterword by the author. "Charming and affectionate. . . . [The novel] rises above the predictable coming-of-age genre on the strength of Manzoor's unflinching honesty and his unique world view. . . . You don't have to be a Springsteen fan to enjoy this book or understand Manzoor's devotion. You just have to recall a time when you were still open enough that music had the power to shatter the world view you inherited." —The Miami Herald "The age-old immigrant's story of hungry hearts and divided loyalties is delivered with uncommon honesty and understanding." — Pico Iyer, Time (Europe) "[ Blinded by the Light ] vibrantly displays a modest and unpretentious sense of optimism, and offers the hope that by connecting with our own choices in music we can transcend cultural and generational differences to reach personal freedom without denying our need to belong." —The Guardian “Wonderful. . . . Manzoor [writes with] insight, compassion, humor and self-awareness.” —The Sunday Times "A clever memoir from an unlikely fan of Bruce Springsteen." —The New York Post “Quirky. . . . Brilliant. . . . Offers an interesting insight into the psyche of an avid fan.” — The Independent “Successfully evokes not only a particular time and place, but, more importantly, a pervasive sense of marginality. . . . A very personal narrative of love, separation, loss and guilt.” — New Statesman SARFRAZ MANZOOR is a writer, broadcaster, and documentary maker. He has written and presented documentaries for the BBC and, prior to his broadcasting career, was a deputy commissioning editor at Channel 4, and before that spent 5 years as producer and reporter on Channel 4 News. His written work has appeared in publications as diverse as the Guardian, Daily Mail, Marie Claire, the Independent, the Observer,Uncut, the Spectator, Prospect, and New Statesman . My Father's House I awoke and I imagined the hard things that pulled us apart Will never again, sir, tear us from each other's hearts `My Father's House', Bruce Springsteen In the summer of 1995 I was twenty-three years old; an unemployed British Pakistani with shoulder-length dread-locks, a silver nose ring and a strange fascination with Bruce Springsteen. It had been six years since I had last lived with my family; having left to study in Manchester there had never been a reason to return to my hometown, Luton. After graduating in economics I had assumed I would be deluged with lucrative offers of employment but these had failed to materialise. While my friends were beginning careers in accountancy and medicine I was most successful at being fired from low-paid temporary jobs: I had been sacked from a data-inputting job for only typing with one hand and doodling with the other, and fired from a credit control agency for having stuck an obscene Public Enemy lyric scribbled on a Post-it to my computer screen. The longest job I had was as a directory enquiries operator. Being a slacker had never been a specific career goal but it was a lifestyle to which I seemed suspiciously suited. My parents had assumed that once I graduated I would return to Luton with a degree and a job, but despite my lack of career and cash I was still not willing to come home. In Manchester I was free; I could stay out late, play music as loud as I wished, wear black leather trousers and red velvet shirts and shake my dreadlocks to Lenny Kravitz. Once a month I would make the three-and-a-half-hour train journey back to Luton to see the family but only out of a sense of obligation. I was barely on speaking terms with my father and most of my conversations with my mother were about how I hardly talked to my father. When I walked through the front door of my parents' home in my blue corduroy jacket with a `Born to Run' enamel badge pinned on its lapel and my rucksack on my back, my headphones still plugged in my ears, I could sense my father's confusion. I knew he was thinking, `What are you doing with yourself?' and the worst part about it was that I could