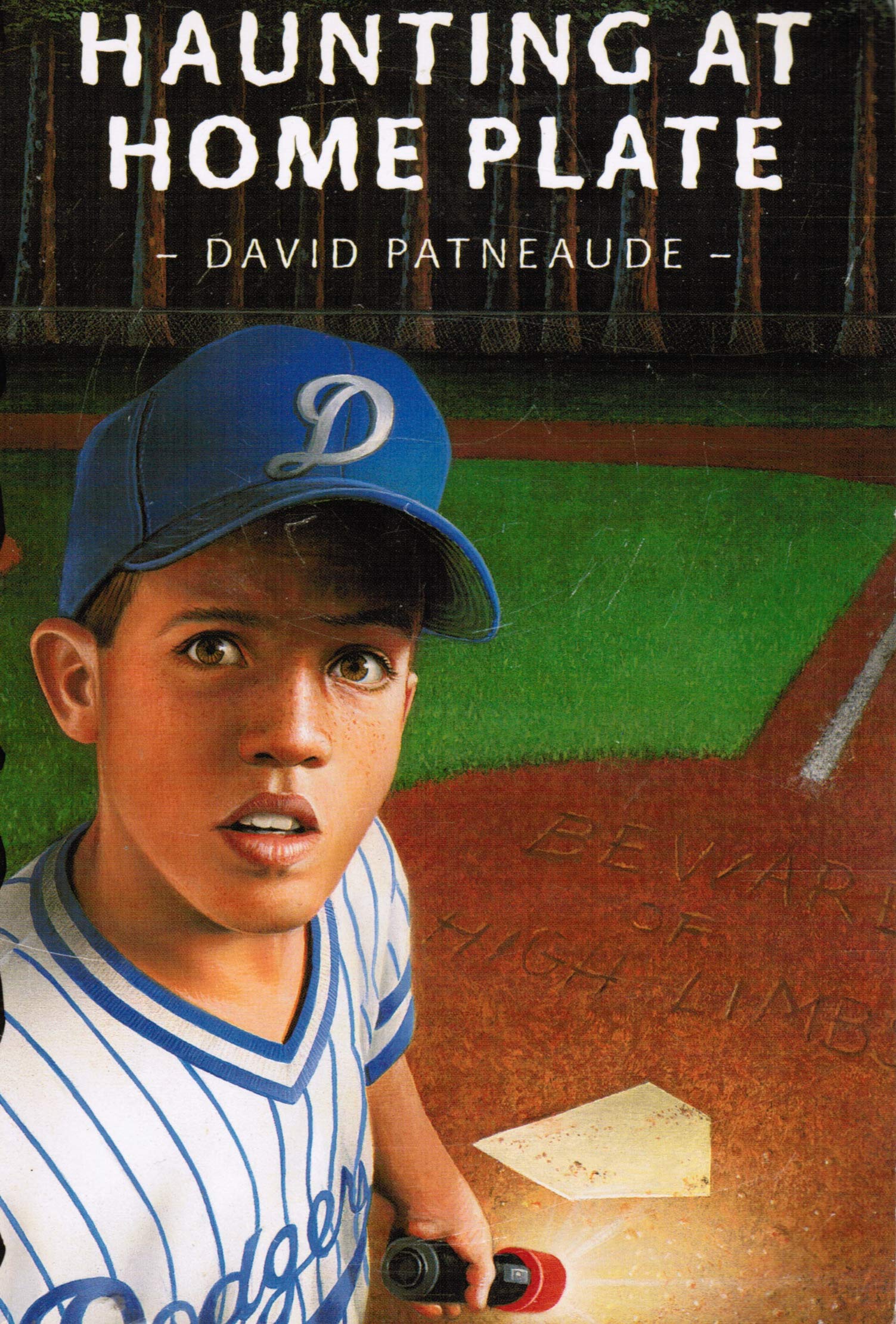

Nelson just wants to play baseball and maybe, one day, realize his dream of pitching. Then his manager is suspended and two players leave the team. On top of that, it seems that the park where the team practices may be haunted. "Young readers who are interested in baseball and like a good mystery will find this title hard to beat." School Library Journal "Fans of baseball and of stories about the paranormal will get their fill from this absorbing novel." Booklist Nelson just wants to play baseball and maybe, one day, realize his dream of pitching. Then his manager is suspended and two players leave the team. On top of that, it seems that the park where the team practices may be haunted. Haunting at Home Plate By David Patneaude Albert Whitman & Company Copyright © 2000 David Patneaude All rights reserved. ISBN: 978-0-8075-3182-2 Contents Prologue — June 14, 1946, 1 * New Season, 2 * May 14, 3 * Phantom Limb Park, 4 * Andy Kirk, 5 * Mudders, 6 * The Giants, 7 * Messages, 8 * A Ghost?, 9 * A Message for Mike, 10 * The Mets, 11 * Nightmares and Dreams, 12 * True and False, 13 * The Cubs, 14 * On Watch, 15 * A Friend, 16 * The Rockies, 17 * Homecomings, 18 * The Expos, 19 * The Tree, CHAPTER 1 New Season I walk back and forth along the riverbank, eyes on the boggy ground. I stoop and rise, stoop and rise, picking up rocks the size of golf balls and bigger. I drop them into a dirty canvas sack and head upstream, where the river narrows to sixty feet. Here the high opposite bank is pockmarked around a rotting stump that angles out from the sandy mud. I dump the rocks on a pile of other rocks: about enough to get my throwing arm built up a little more, to get me ready for the day Mr. Conger calls on me to step to the mound and fire that first pitch. It's possible he will. My dad says if I practice, anything is possible. And if I have to practice without him, this is the best place to be. I stand tall and twist from side to side before picking up a rock and throwing it easily toward the stump on the opposite bank. Halfway across, it splashes into the muddy water. The ripples stretch out, move downstream, and disappear. The next rock flies a little farther, the one after that farther still. On my tenth throw, the rock reaches the bank, pocking the mud. The next one thuds into the stump, scattering mushy red pieces of wood. I close my eyes and picture a baseball thumping into a catcher's mitt: Emmett's mitt catching, my arm pitching. I keep throwing, increasing my speed. The stump takes a beating as I rifle the stones across the water. Finally, the pile of rocks is gone. I stop, shrug out my muscles, stare across the river at the pattern of holes in the opposite bank, fading in the March twilight. The sun has slipped behind the layer of clouds that blankets the distant peaks of the Olympic Mountains, white-capped, gray-shouldered ghosts of Washington's northwest coastline. I pick up a flat rock from a smaller pile, then take a step forward and throw, aiming to skip it. The rock skims low to the middle of the river before setting down, lifting off, setting down, lifting off. It skips four times and plops into the mud. As the sky darkens I skip more rocks, until I'm down to one. I pick it up, kick high, and dip low, releasing it fast and flat. It barely kisses the surface, dancing across the water and thudding into the bank. I return to my bike and pedal away from the river. * * * Pure dark has set in by the time I get to town. Waves of cold rain roll out of the sky, matting down my hair, soaking through my sweatshirt and jeans. I take the shortcut through the grounds of the junior high. At the far end of the parking lot, I stop at the sound of a too-familiar voice. Down on the track, under the lights, two figures lean against the wind. Mr. Conger, huddled under a striped golf umbrella, growls orders to his son, Gannon, whose dark hair is glossy-wet and glued in strands against his forehead. Neither of them sees me. I quietly angle my bike toward a small clump of fir trees. I squeeze past wet branches until my bike and I are both out of sight. "Three more sets," Mr. Conger says. Gannon turns toward the short, steep hill that rises to a chain link fence fifty feet away. His dad raises a stopwatch. Gannon jumps up and down in place. His sweatshirt and sweatpants are heavy with rain, and they hang and flop on him like wet laundry. He lowers himself to a crouch, ready. "Go!" his dad says, and Gannon stumbles forward, losing his footing on the slick cinder surface before reaching the grass. He sprints ahead, arms pumping, head down. He tops the hill, touches the fence, turns and jogs back down. At the bottom he drops to the track and does five quick push-ups before heading back up the hill. He repeats the routine over and over — nine more times, I count — then stops at the bottom, hands on his knees, breathing deep. "Stand up," his dad orders. "That set was slower. You