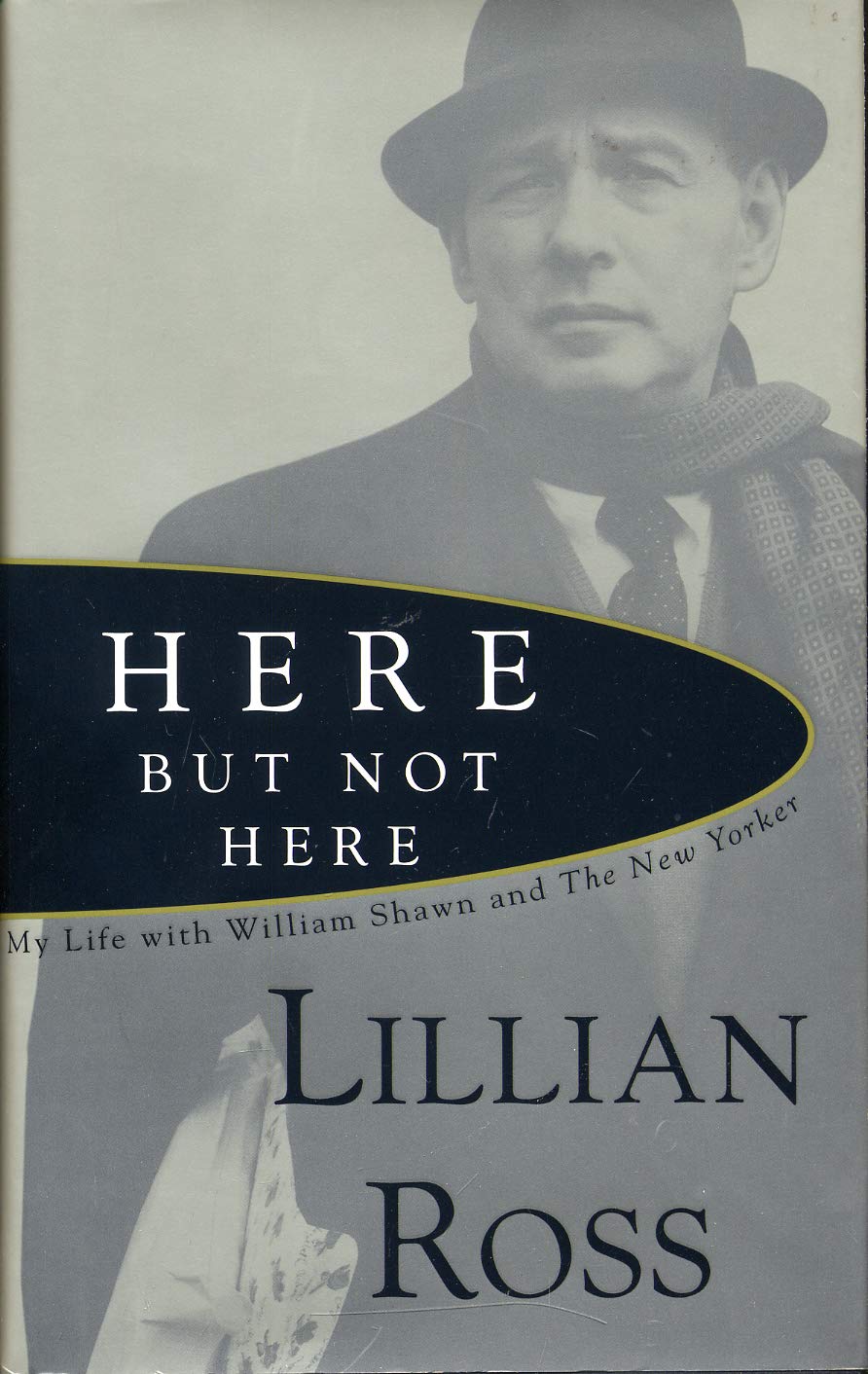

In this fascinating and beautiful memoir, the renowned New Yorker writer Lillian Ross tells a remarkable love story of the passionate life she shared for forty years with William Shawn, The New Yorker's famous editor. "All enduring love between two people, however startling or unconventional, feels unalterable, predestined, compelling, and intrinsically normal to the couple immersed in it, so I would have to say that I had an intrinsically normal life for over four decades with William Shawn. . . . I have a lasting sense of the normalcy of it all. It was a normalcy that Bill Shawn was able to create for himself and for me against all normal odds." Shawn was married, yet Ross and Shawn created a home together a dozen blocks south of the Shawns' apartment, raised a child, and lived with discretion. Their lives intertwined from the 1950s until Shawn's death, in 1992. Ross describes how they met and the intense connection between them; how Shawn worked with some of the best writers of the period; how, to escape their developing liaison, Ross moved to Hollywood, and there wrote the famous pieces that became Picture, the classic story of the making of a movie--John Huston's The Red Badge of Courage--only to return to New York and to the relationship. The love of Shawn and Ross for each other made it impossible for them ever to part. ---- This book is a gem, an exquisitely told real-life story more potent than fiction. As John Cheever's stories from the New Yorker magazine demonstrate, in the upper-crust Northeast in midcentury, when divorce simply wasn't done, adultery was not exactly unheard of. But Lillian Ross's exposé of her own decades of adultery with her sainted boss, New Yorker editor William Shawn, still comes as a shock. It's doubly shocking because he was uniquely revered and had an upright if not asexual reputation and because members of the New Yorker family seldom spill the beans. Gossip connoisseurs will gorge on Ross's tasty tidbits. As a child in Chicago, Bill Shawn narrowly escaped murder by renowned thrill killers Leopold and Loeb, who left Bill's house and kidnapped Bobby Franks instead. Bobby died and Bill became a famously shy victim of phobias--blood, violence, heights, confinement, or darkness could make him, in his own self-imploding way, go postal. When Bill's mom hired a nurse to save him from scarlet fever, the nurse "decided he needed, in addition to nursing, some sexual education. 'To my astonishment, she provided both, but I don't think it did me any harm,' Bill told me." He was then a child of 12. It does not occur to Ross that sex might have long-term effects of any consequence. She feels zero guilt that she set up a love nest in Marlene Dietrich's old apartment 10 blocks from Shawn's family, and adopted a child, and had a phone put in by Shawn's bed, and spent Christmases with him, leaving Thanksgivings free for Shawn to spend with his wife and biological children. "Bill assured me that Cecille was going along with our arrangements. From time to time, I would think: Maybe she loves him so much she wants him to have what keeps him alive." Meow! Mrs. Shawn, as Ved Mehta notes in his 1998 book, Remembering Mr. Shawn's New Yorker , was a reporter who supported her husband when they got to New York, and even got him his fateful job at the magazine, prior to devoting herself to their family. Ross got assignments from Shawn that made her famous, but she notes, "We never experienced even a moment of 'conflict of interest' problems, for the simple reason that we never had any conflict of interest.... If I wanted to see Bill in his office, I called his secretary, like everyone else." "I have always been less inclined than most people I know to indulge in self-analysis," writes Ross. She may be a renowned reporter, but her own mind is one subject that entirely escapes her notice. Annoyed that romantic emotions were spoiling her mood when her career took off in 1950 ("I felt I should have been having a lot of fun. Instead, I was being emotionally distracted and drained"), Ross did what any disgruntled journalist would do. She spent a year and a half at company expense in Hollywood, playing tennis with Charlie and Oona Chaplin, bonding with Bogart and Bacall, and writing the classic book Picture about her dear friend John Huston's movie The Red Badge of Courage . Ross became an A-list partygoer, the first major showbiz reporter with highbrow credentials, and Huston and company handed her a story much better than the movie in question. "I thought I was the luckiest reporter in the history of journalism," writes Ross, who may be right. And no wonder she was such a hit: cute, connected, willing to listen to egomaniacs and let subjects read her drafts before publication, Ross was, like the showbiz-titan pals of Carrie Fisher that are celebrated in her Hollywood roman à clef Delusions of Grandma , "ruthless and glad." But Ross's impersonal journalism method works bet