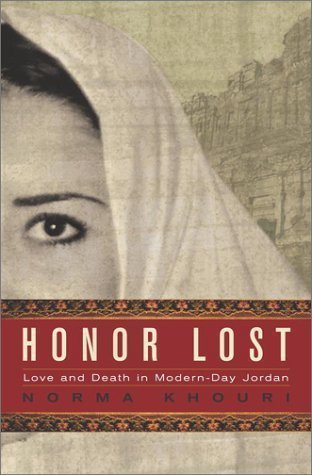

A thought-provoking story of friendship, love, and tradition set against the backdrop of modern-day Jordan recalls the tragic story of the author's best friend, Dalia, who was murdered by her own father for falling in love with a young Catholic man, in a poignant plea against the practice of honor killing. Reprint. 40,000 first printing. The Washington Times Terrifying and inspiring. -- Review Norma Khouri is a poet and author of short fiction. As a result of the events recounted in Honor Lost, she was forced to leave Jordan. She lives in Australia. Chapter One The cluttered break room in the back of N&D's Unisex Salon was not much to look at. Twenty years' worth of scuff marks marred the once-white walls and the tile floor whose warm earth beige once had shone, but which were now a dull yellow-gray. The scruffy brown couch to the right of the door looked like a battered old man, pockmarked by time. But Dalia, my best friend, and I knew the room's true value; to us it was a haven, a sanctuary, the only place where we had the privacy and freedom to share our secrets, hopes, dreams, fears, and disappointments. That couch was the same one we'd sat on at the age of thirteen when we pledged that nothing and no one would ever destroy our friendship. We were like sisters, born a couple of months apart in 1970. Living as close neighbors in the Jebel Hussein district of Amman, we met at a neighborhood park when we were three and, almost instantly, were inseparable. We each had four brothers and very strict parents. And, despite the fact that we were from different religions -- her family was strict Muslim, while mine was Catholic -- we faced similar obstacles growing up that only strengthened the sisterly bond between us. Though Jordan is a nation of rich and poor -- the rich living in million-dollar villas and the poor in refugee camps -- our families were part of the comfortable middle class that lived in houses handed down through their families for generations, and fathers who worked at respectable jobs; mine had his own contracting business, Dalia's was an accountant for a large insurance company. But we were not of the class that skimmed the cream of opportunities for women -- the elite who automatically sent their daughters abroad to universities to live and study. Our parents never showed a hint of ambition for us, beyond marriage. By the time we entered our teenage years, we'd decided that we could forge the best future for ourselves by finding a way to stay together. At fifteen, we discovered that Jordanian women were allowed to own and operate beauty parlors, one of the few careers open to them. Higher dreams didn't seem possible. And Dalia and I believed that having our own business would guarantee that we could remain together. So, armed with a plan, we started taking the necessary steps to set up our business. Our first move was to assure our parents that we were not college material. We easily maintained "C" averages, convincing them that this was the best we could do. In a country where a man's education carries more weight than a woman's, our lackluster performance did not worry either set of parents. Next, we suggested that we enroll in beauty school and, given our bleak college prospects, our families did not object -- in fact they encouraged us to go. So, at eighteen, Dalia and I learned our trade. And, after finishing school and working at several places, we were able to complete our final step. Although we didn't see it at the time, we were already using one of the few powers Jordanian women have: to bend their intelligence and imagination to plotting and planning to outwit men to get what they wanted. We would become masters. It didn't occur to us that the effort we spent on conspiring and manipulation might have been turning us into doctors or software designers. Achievement was in tricking the men who controlled our lives; it was survival in an unequal world, as we saw it. "You know, I think if we complain a bit longer about working at this salon, our fathers will agree to let us open our own place, if only to shut us up. My father seems ready to agree, how about yours?" Dalia asked me one day, her eyes betraying a hint of conspiratorial glee. "Mine's getting tired of the complaints. But we'd better be careful; they could decide that we should stop working and stay home. I keep telling them that we love the work, we just hate the working conditions." I laughed. "Me, too, and I think our fathers will go for it. Look at it from their point of view, they'll have an easier time keeping an eye on us this way." Until we were safely married and under the thumb of our husbands, we'd be watched every day, every hour, by our fathers and brothers. In the end, we persuaded our parents to invest a small fortune in our salon. Our idea was to renovate a portion of a two-story building owned by my father. No one had used the old, stone-front structure, which was close to both of our