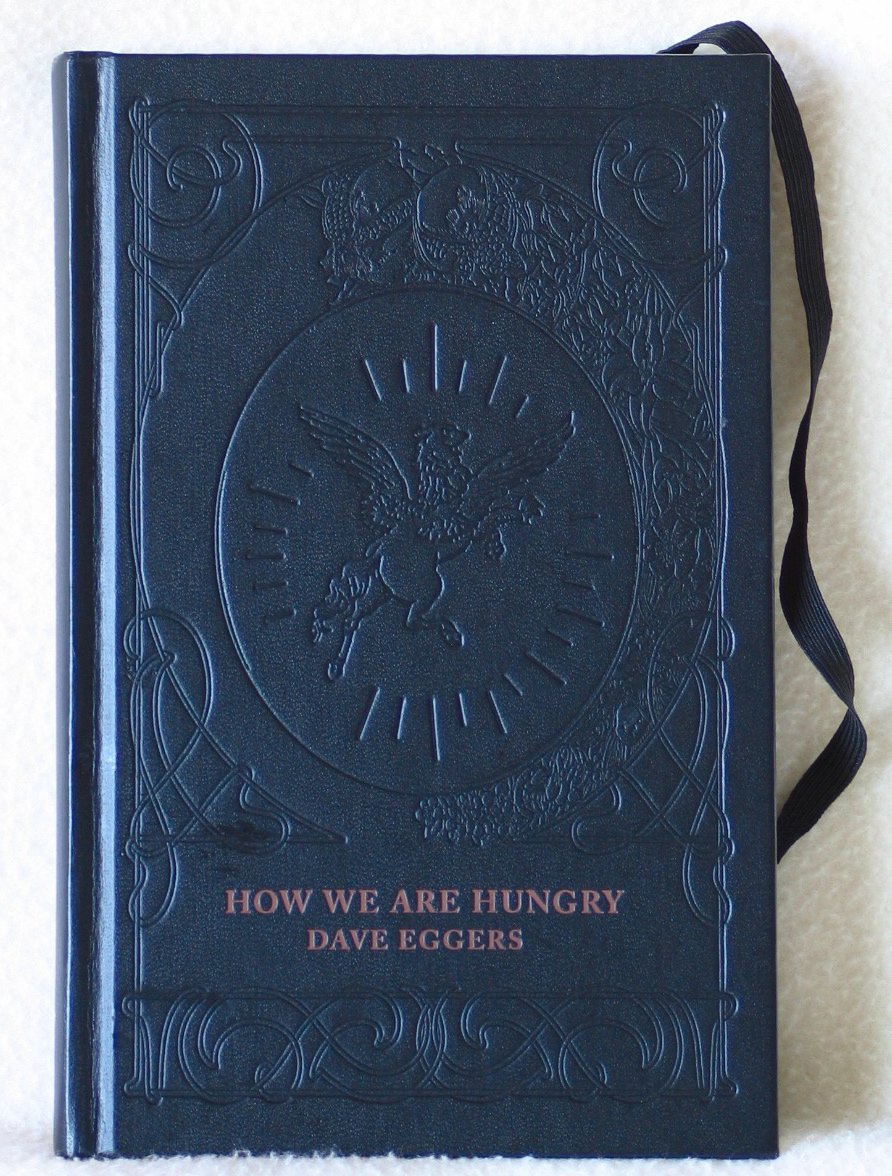

Dave Eggers presents his first collection of short stories. The characters are roaming, searching, and often struggling, and revelations do not always arrive on schedule. Precisely crafted and boldly experimental, How We Are Hungry simultaneously embraces and expands the boundaries of the short story. In this collection, Eggers ( Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius ) is obviously straddling the line between being a writerand a very talented one at thatand being the spokesman for the new age of self-conscious writing. Reviewers are unanimously unhappy with a few of his literary pranks here. "There Are Some Things He Should Keep to Himself," for example, offers up five blank pages. But when Eggers throws off our expectations and starts writing, he shines. His longer stories are original, witty, and truthful. As his characters search for transcendence, Eggers and his readers are right there with them. Copyright © 2004 Phillips & Nelson Media, Inc. In his first collection of short stories, Eggers shows himself to be, well, serious. Gone is the charming, smirky, self-conscious narrative voice that helped make A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius (1999) so popular. Aside from the story "There Are Some Things He Should Keep to Himself," which consists of five blank pages, these short stories are unrelentingly sincere--sometimes too much so. Many of these stories feature Americans abroad--a man alone in Egypt, a woman (also alone) in Tanzania preparing to climb Kilimanjaro. In the collection's best story, "The Only Meaning of Oil-Wet Water," two old friends reunite in Costa Rica for a kind of loveless love affair. The accumulation of details--surfing together in the oil-wet water, an injured anteater in their hotel room--brings the story a haunting power. But some of the stories don't come together as well, and Eggers' fans may be disappointed that almost none crack a smile. Still, Eggers imagines emotionally and symbolically resonant scenes as well as any of his contemporaries, and this collection has several great ones. John Green Copyright © American Library Association. All rights reserved These tales reinvigorate that staid old form, the short story, with a jittery sense of adventure. -- San Francisco Chronicle omments on previously-released stories: "The Only Meaning of the Oil-Wet Water," originally published in Zoetrope: All Story , was named a finalist for the National Magazine Award for Fiction, and included in the Best American Magazine Writing 2004. "Up the Mountain Coming Down Slowly" is a masterpiece . . the narration is magisterial, without a false note. It may well be the last great twentieth-century short story. -- The Observer , (London) "After I Was Thrown in the River and Before I Drowned" is a small tour de force that ratifies [Eggers¹s] ability to write about anything with style and vigor and genuine emotion. --Michiko Kakutani, the New York Times Dave Eggers is the editor of the quarterly journal McSweeney¹s and of a yearly collection for younger readers, The Best American Nonrequired Reading . He edits that collection with high school students from 826 Valencia, the educational nonprofit he founded in 2002. 826 Valencia seeks to involve the community in after-school and in-school tutoring in English and writing. Eggers is currently at work on It Was Just Boys Walking , a biography of Valentino Achak Deng, a refugee from Sudan now living in Atlanta; and Teachers Have It Easy , about the need for higher teacher salaries, coauthored with Ninive Calegari and Daniel Moulthrop. Eggers teaches writing at 826 Valencia and journalism at UC Berkeley¹s Graduate School of Journalism. Look carefully at the black, dust-jacketless cover of Dave Eggers's mixed bag of a short-story collection, How We Are Hungry, and you'll see the engraved image of a gryphon, the mythological animal with the body of a lion and the wings of an eagle. It's the sort of thing that barely registers before you've begun reading. But after you've turned the last page and closed the book, there it is again -- and suddenly this hybrid beast, famed as much for its vigilant nest-tending as for its love of gold, seems a particularly apt symbol for the other unusual creatures about whom you've just read. Animals, especially imperiled animals, make ominous cameos in nearly all of these stories. There's the wounded anteater who crashes the hotel room of two old friends, both of whom seem willing to sacrifice their friendship for a few nights of banal, artificial romance. There are the thousands of cows whose imprisonment in a beef-processing plant haunts a young man, himself imprisoned by a relative's blithe and repeated attempts at suicide. There's the sheep struck and killed on the road by a driver rendered temporarily insane with unfocused, diabolical jealousy. And in the last and most curious story, there's a chatty talking dog named Steven, who narrowly survives being thrown in a river and commits the remai