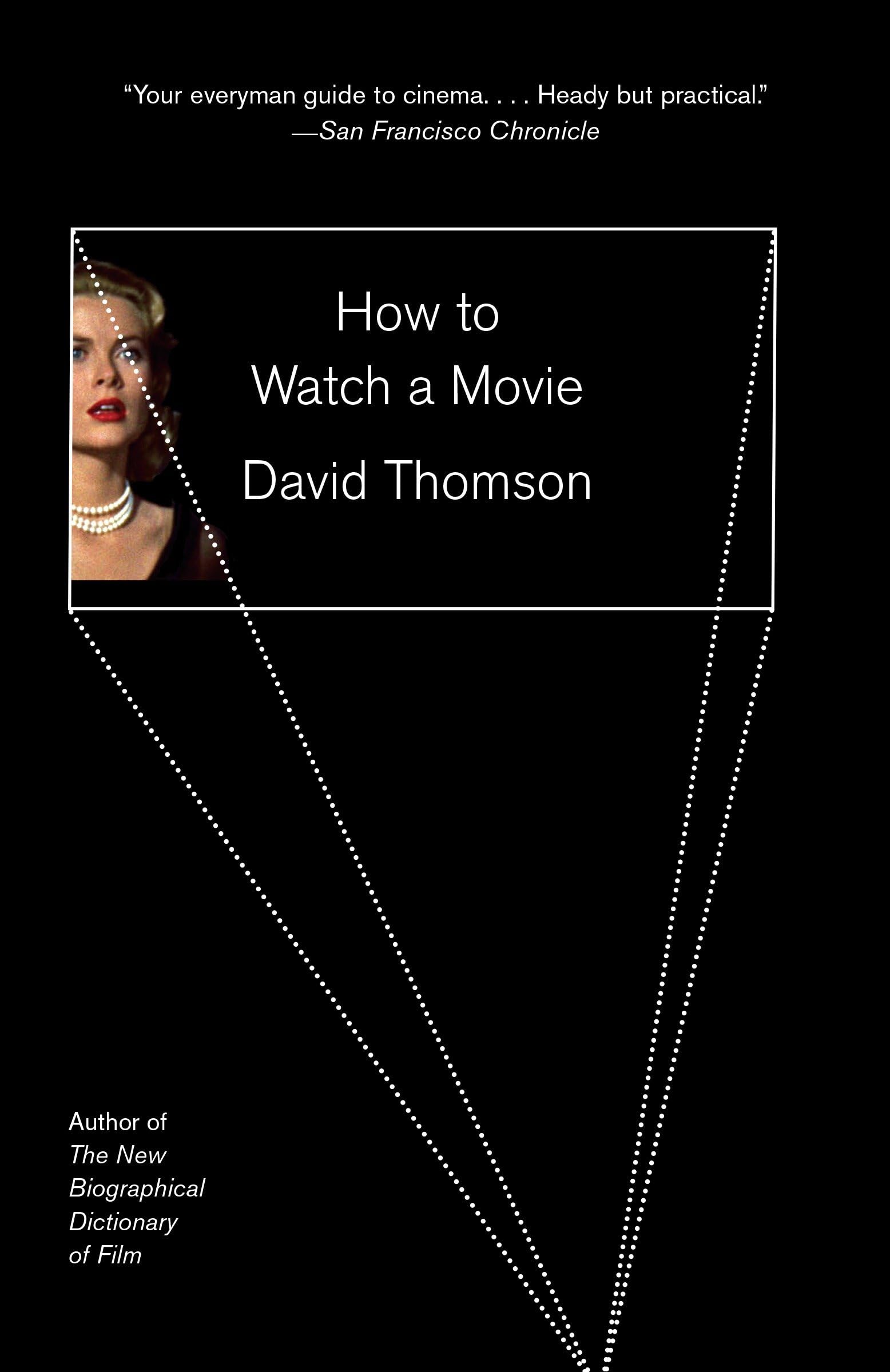

In his most inventive exploration of the medium yet, David Thomson—one of our most provocative authorities on all things cinema—shows us how to get more out of watching any movie. Guiding us through each element of the viewing experience, considering the significance of everything from what we see and hear on-screen—actors, shots, cuts, dialogue, music—to the specifics of how, where, and with whom we do the viewing, Thomson explicates the movie watching experience with his customary candor and wit. Delivering keen analyses of films ranging from Citizen Kane to 12 Years a Slave , in How to Watch a Movie, Thomson shows moviegoers how to more deeply appreciate both the artistry and the manipulation of film—and in so doing enriches our viewing experience immensely. “Your everyman guide to cinema. . . . Heady but practical.” — San Francisco Chronicle “A love story. . . . A book that will get you thinking about the magic of film.” —NPR “David Thomson’s love affair with the movies is one of the great blessings of our culture. How to Watch a Movie confirms yet again that he has the most learned and independent eyes in the criticism business. Somehow he freshens everything.” —Leon Wieseltier “Chatty and authoritative. . . . Both wonderfully informative and a beautifully written paean to the movies and their continuing ability to inspire and enthrall.” — The Sunday Times (London) “Easygoing, essayistic. . . . This isn’t an academic manual or Movies for Dummies . You read Thomson for contact with an urbane and provocative intelligence.” — The Washington Post David Thomson has written about film for The Guardian, The Independent, The New York Times, The New Republic, Salon, Movieline, Film Comment, and Sight & Sound . He is the author of more than thirty books on film, including The New Biographical Dictionary of Film, Rosebud: The Story of Orson Welles, and The Whole Equation: A History of Hollywood . He lives in San Francisco. 1 ARE WE HAVING FUN? Some people believe film critics are cold-blooded. Whereas many audiences hope to come away from a movie shaking with fear, helpless in mirth, or simply bursting with happiness, a critic sneaks away from the show, a little hunched, with a secretive smile on his face. It’s almost as if the film were a bomb, or a bombe, an artful explosion, and the critic was a secret agent who had planted it and now takes a silent pride in the way it worked. And how it worked. Audiences believe they deserve a good time, and some feel that dismantling the machine can get in the way of the fun. That’s some people—thank God it’s not you. If it were you, you wouldn’t be holding me in your hand or your lap, ready to read a book about how to watch a movie. Your being here suggests you feel the process is tricky enough to bear examining. In the first sixty years or so of this medium, the cinema behaved as if pleasure was its thing, and its only thing; but in the sixty years since, new possibilities have emerged. One is that pictures are not just mysteries like The Maltese Falcon or The Third Man, but mysteries like Blow-Up and Persona, or Magnolia or Amour, which ask, well, what really is happening, what do these cryptic titles mean, and what are those frogs in Magnolia meant to be? There is something else: a wave of generations now think some movies might be as fine as anything we do, as good as ice cream or Sondheim, things you can’t get out of your head, where watching (or engagement) becomes so complex and lasting that you may welcome guidance. In the 1960s, when “film study” first took hold in academia, there were well-meaning books that tried to explain what long shots and close-ups were, with illustrations, and what these shots were for. Such rules were at best unreliable. They felt as if assembled by thought police, and they depressed anyone aroused by the loose Bonnie and Clyde –like impulsiveness on screen. I pick that film because it’s symptomatic of a sixties energy in movies, a feel for danger and adventure: hang on, this is a bumpy ride, and should we be having such fun killing people? Is it a genre film about 1932 or some cunning way of talking to 1967? I’m more interested in discussing that experience: the way film is real and unreal, at the same time; what a shot is, or can be, and a cut; how we work up story from cinematic information and the helpless condition of voyeurism; what sound does (its apparent completion of realism, as well as its demented introduction of music in the air); the look of money in movies (no art has ever been as naked about this, or such a prisoner to it); the everlasting controversy over who did what; and the myth known as documentary (is it salvation or just another story-telling trick?). More than that, the ultimate subject of this book is watching or paying attention (that encompasses listening, fantasizing, and longing for next week) and so it extends to watching as a total enterprise o