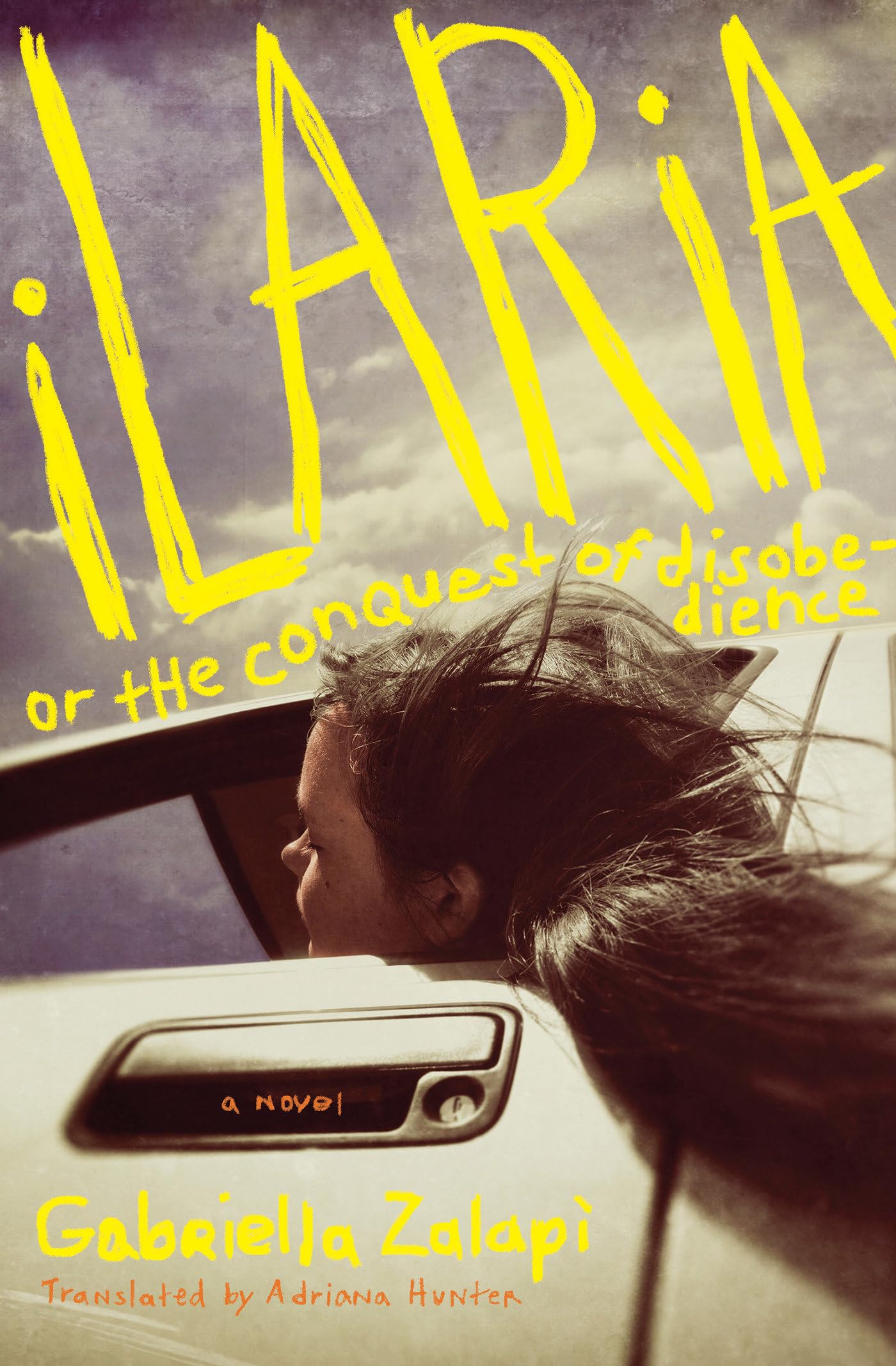

Kidnapped by her troubled father, a young girl navigates life on a road trip across 1980s Italy in this stunning, cinematic English-language debut. One day in May 1980, 8-year-old Ilaria gets into her father’s car after school. As they stop at a series of highway hotels, traversing the north of Italy, the child thinks of her mother and promises herself not to cry anymore. She learns to drive and to lie, discovers Trieste, Bologna, a boarding school in Rome, a sunny rural life in Sicily. Thanks to the games they play, the hit songs they sing at the tops of their voices on the road, and the kind people Ilaria meets along the way, the kidnapping almost seems like a normal childhood. But her father drinks too much, nervous in a cloud of cigarette smoke. If he takes her by the hand, she thinks it’s better not to pull it away. Ilaria observes and feels everything. In gripping, precise prose, this poignant novel takes us inside the mind of a little girl who must grow up on her own. “A propulsive coming-of-age story set against the political violence of Italy’s Years of Lead…Zalapì sketches a clear and sensitive portrait of her young narrator…This leaves a mark.” — Publishers Weekly “A nuanced portrayal of a child’s lost years with a flawed and irresponsible parent.” — Kirkus Reviews “The story captivates the reader with a precision as minimalist as it is disarming.” — Vogue (France) “A deeply moving novel about family love and its contradictions, the end of innocence, and the disobedience of a young girl looking for freedom.” — Elle (France) “A story tinged with dread but, above all, bursting with sensitivity.” — Le Monde Gabriella Zalapì is a visual artist of English, Italian, and Swiss origin who lives in Paris. Trained at the Haute école d’art et de design in Geneva, she draws her material from her own family history, taking photographs, archives, and memories and combining them in a disturbing interplay between history and fiction. Her debut novel, Antonia , won the Grand prix de l’héroïne Madame Figaro and the Prix Bibliomedia. Adriana Hunter studied French and Drama at the University of London. She has translated more than ninety books, including Marc Petitjean’s The Heart: Frida Kahlo in Paris and Hervé Le Tellier’s The Anomaly and Eléctrico W , winner of the French-American Foundation’s 2013 Translation Prize in Fiction. She lives in Kent, England. MAY 1980 Aged eight, I like the sensation of my upper body dangling free, the contact of my knees hooked over metal. I like the moment when I close my eyes tight, let go of the bar with my hands, and feel the giddiness thrill through me. When my hands are flat on the black asphalt, that means I’ve overcome my fear. And that’s when I picture my favorite gymnast, Nadia Comăneci. She has her arms spread wide. Victory. I adopt this hanging position whenever we have recess or I’m waiting for Ana, my sister. When she left me this morning she said, See you back here on time , okay? Or I’ll go home alone. “Here” is at the foot of the steps, near the metal rail that separates the parking lot from the schoolyard. Ilaria! Get down from there! We’re going to Chez Léon. Come on, move it! I recognize Dad’s voice. Surprised, I lift the bottom of my dress that’s blocking my view. Those are definitely the tips of his shoes, that’s definitely his impatient voice. I swivel around the bar, land on my feet, and smooth down my dress. Ana’s about to show up. No, no. Change of plan. Mom’s picking her up from school and we’re meeting at Chez Léon. Come on! I take his hand, it’s clammy. Since our parents separated and Dad moved to Turin, we meet at a restaurant once a month. It was Mom who came up with the idea. She prefers neutral territory. She says they fight too much at home. And it’s true, they do hold back at Chez Léon. Even if Dad does clench his jaw and Mom stares into space, pretending not to care. No, Dad still hasn’t found a job. When he says “Nope-no-work” his voice is always sad, tired. Mom turns away slightly to hide her smile and Dad gets mad. He uses the word “humiliation” a lot. Luckily, the waiter comes over and puts down plates of perch fillet or bowls of meringue with whipped cream. Thanks. After dessert, Ana and I get up from the table and go out to the small beach where we choose pebbles. We practice skipping stones. Did you see? What? Dad took Mom’s hand. To get to Chez Léon we go through the village of Hermance, cross the French-Swiss border, and keep going along the road to Yvoire. Dad has a navy blue BMW, a 320 coupe. Tell me if you see a phone booth. He lights a cigarette. There! He stops, gets out, and produces some coins from his pants pocket. His back pressed to the glass, the creases in his shirt making v and w shapes. I wait, lower my window to let in some air. The leather seat no longer burns the backs of my thighs, it even feels soft when I stroke it. Inside the phone booth, Dad’s talking loudly. He raises hi