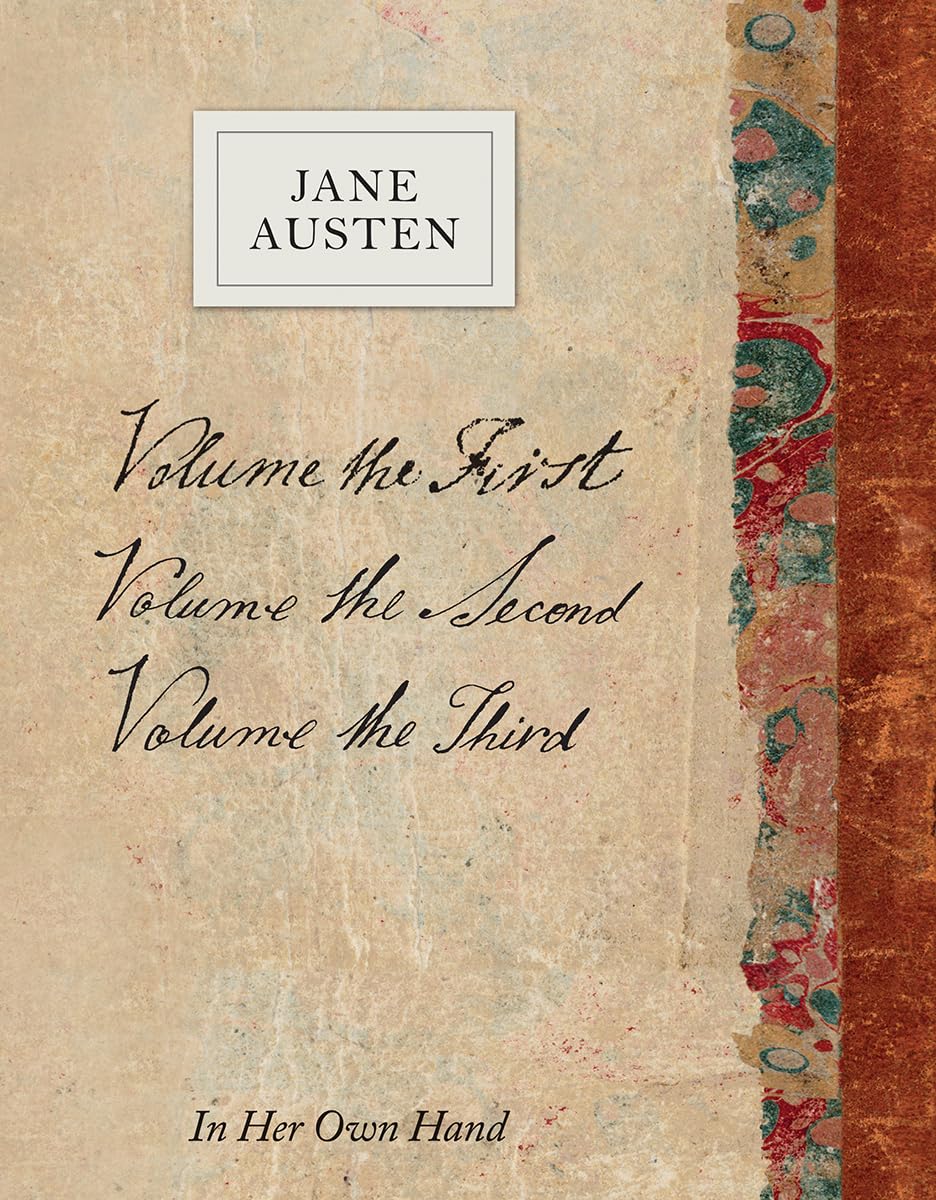

For the first time, all three volumes of Jane Austen’s brilliant early manuscripts are available in beautiful facsimile editions. Forever immortalized as the author of Pride and Prejudice , Jane Austen actually produced her first “books” as a teenager. Taking their names from the inscriptions on their covers―Volume the First, Volume the Second, and Volume the Third―these brilliant little collections include the stories, playlets, verses, and moral fragments she wrote likely from the ages of twelve to eighteen. As a young author, Jane Austen delighted in language, employing it with great humor and surprising skill. She was adept at parodying the popular stories of her day and entertained her readers with outrageous plot lines and characters. Kathryn Sutherland, in her introductions, places Austen’s earliest works in context and explains how she mimicked even the style and manner in which this contemporary popular fiction was presented and arranged on the page. None of her six famous novels survives in complete manuscript form. This is a unique opportunity to own likenesses of Jane Austen’s notebooks as originally written―in her own hand. The In Her Own Hand series boxed set contains facsimile editions of Jane Austen’s fiction, in her handwriting. The books include transcriptions by R. W. Chapman first recorded in 1953. In Her Own Hand boxed set of all three volumes includes: Volume the First Volume the Second Volume the Third "This beautiful edition places Jane Austen’s three precious notebooks into the hands of the common reader." ― Jane Austen Society of North America (JASNA) Jane Austen (1775―1817) is one of the most beloved novelists in the English language. Her novels Sense and Sensibility, Pride and Prejudice, Emma, Mansfield Park, Northanger Abbey, and Persuasion have left readers with a literary legacy hard to match by any author before or since. Excerpt from In Her Own Hand: Volume the Second Introduction Teenage Reading and Rebellion As its mock-solemn title implies, Volume the Second is the second in the series of notebooks into which the teenage Jane Austen copied her early compositions. This is the most finished of the three collections; it is also the longest (with 252 pages) and the most carefully structured. Twelve leaves are missing from its original structure, five of them taken from the end, most likely removed at the time of writing into the notebook. No empty space is left, and there is no obvious development in the young author's hand to suggest that she worked on the entries over a long period. Internal dating (from June 1790 to January 1793, when her niece Fanny Austen was born) link the contents with a period of high productivity, particularly intense between the ages of fifteen and sixteen. Where the truncated fragments of Volume the First riot in joyous disorder, barely anchored by their network of family dedications, the pieces assembled here achieve a more unified sensibility without sacrificing any of their comedy. Indeed, Volume the Second has a good claim to be Jane Austen's funniest work; it is impossible not to laugh out loud while reading it. The manuscript is made up of nine items: two works identified by the author as novels” (Love and Friendship” and Lesley Castle”); a spoof History of England”; A Collection of Letters”; and five Scraps”, among them the single act of a comic play which conclude the volume and form a matching bookend to the mini anthology of Miscellaneous Morsels” or Detached Pieces” that round off Volume the First. Dedicated to her firstborn nice, Fanny Austen (as those inserted at a slightly later date into Volume the First are to her second niece, Anna Austen), these final sketches openly mocked the restrictive educational diet proposed for young ladies and the narrow role of moral guide laid down for spinster aunts. Young Aunt Jane will have none of it; instead, the final pages of both notebooks seal a more subversive contract with the next generation of Austen females. As she writes here to Fanny, only weeks old”I think it is a my particular Duty to prevent your feeling as much as possible the want of my personal instructions, by addressing to You on paper my Opinions & Admonitions on the conduct of Young Women, which you will find expressed in the following pages” (p. 237). Opinions & Admonitions on the conduct of Young Women” offers a good way into understanding the structure and contents of Volume the Second, with its sustained onslaught on the conventional limits on female behavior. Other hints as to how to read the collection are provided in its repeated use of epistolary form, and especially the novel in letters, and its focus on sensibility as a facet or modifier of behavior. The late eighteenth century saw a proliferation of works featuring heroes and heroines of sensibility; that is, characters sympathetic to the sufferings and feelings of others. Where knockabout humor dominated Volume the Fir