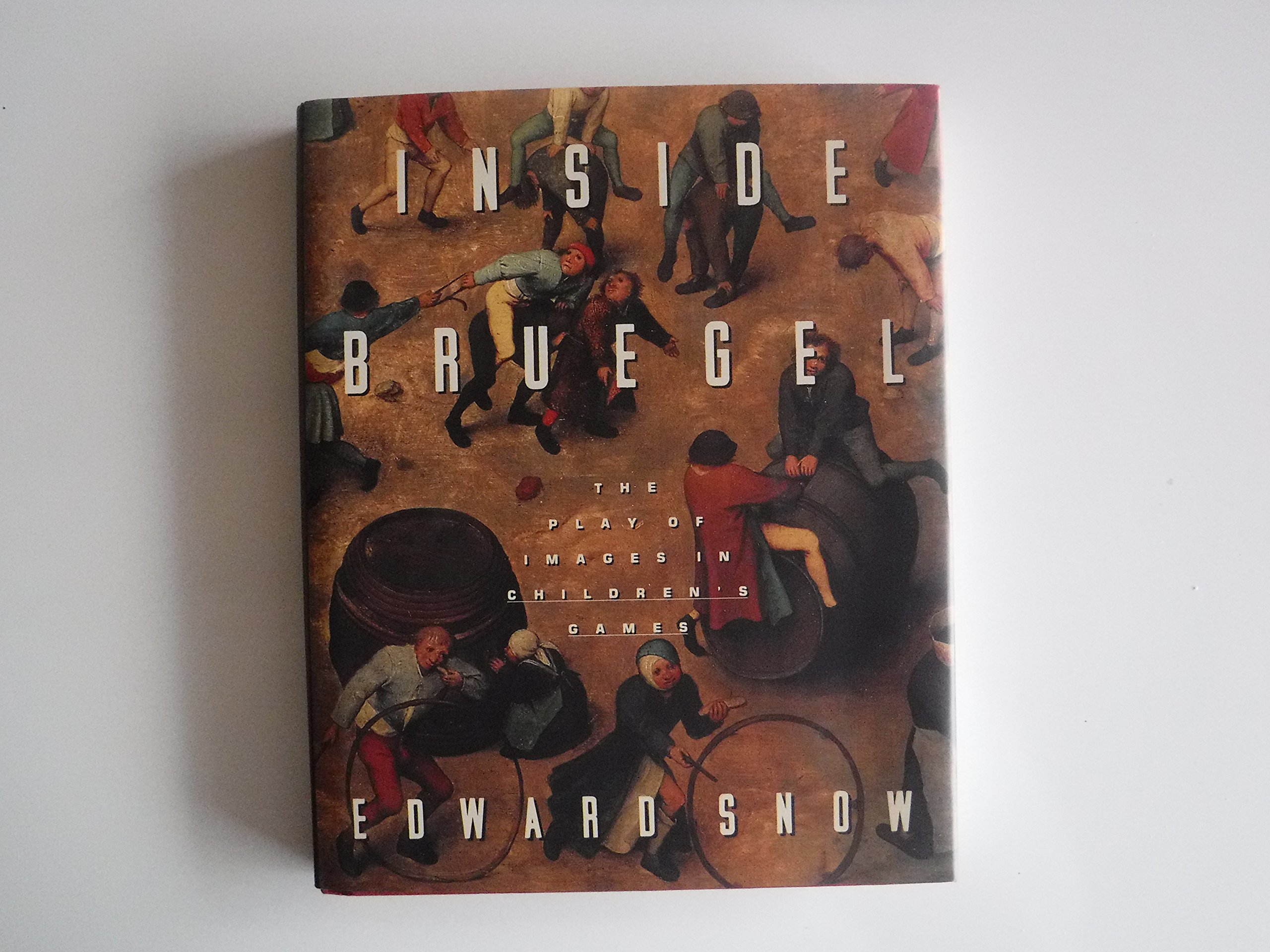

In this brilliant, original and lavishly illustrated book, Edward Snow undertakes an inquiry into a single painting by the Flemish master Peter Bruegel the Elder—the kaleidoscopic Children’s Games—in order to unlock the secrets of the great painter’s art. Translator and art historian Snow (English/Rice Univ.; A Study of Vermeer, not reviewed) turns a close reading of the multifarious Bruegel into a colorless exercise in pedantry. The Elder Bruegel's range of subjects and richness of detail make it easy to structure a whole book around the imagery of his paintings, a task to which Snow, alas, brings jargon-mongering and donnish analysis. Any art historian would of course be attracted to Bruegel's scope of accomplishment--peasant genres, Bosch-like fantasies, religious histories, parables, landscapes--and his combination of Dutch realism, Renaissance humanism, and medieval motifs. His painting Children's Games, for instance, with its minute social observation, masterful composition, myriad details, and underlying moral subtleties, make it a favorite subject of study. Snow not only examines the significance of almost each frolicking group in the painting, but also contrasts, not always convincingly, the figures with those in other Bruegel canvases. The games Bruegel's children play are not the moralized images of his Netherlandish Proverbs, however, though the two paintings are similarly crammed; nor is the composition of the carefully structured Children's Games as straightforwardly realistic as Peasant Dance. Snow's efforts unfortunately turn into academic interpretations of other academic interpretations or spiral into abstruse theory-speak, featuring ruminations on the ``unstable libidinal field'' of a painting or the ``oasis of pre-volitional well-being'' in a work. Snow may be sensitive to the problem of our aesthetic responses to an artist so subtly nuanced and historically distant, but his impulse is toward amorphous hermeneutics rather than the essence of the images before him. Reading into Bruegel's paintings, Snow renders the Dutch artist, in recondite prose, into an abstract impressionist. ``They were never wrong, the Old Masters,'' as Auden writes, but the same can't be said for this particular commentary on one of those masters. (150 b&w illustrations, one color plate, not seen) -- Copyright ©1997, Kirkus Associates, LP. All rights reserved. “Edward Snow has an eye—and a mind—for details. He has lovingly ventured inside Bruegel’s Children’s Games, and his intense, intimate prose enables us to linger in the vast, sprawling scene, savoring each of the marvelous figures and pondering their rich and complex interrelations. This extraordinary sustained act of critical attention will transform our understanding of Bruegel’s art and help to illuminate the meanings of that most elusive and precious human activity, play.”—Stephen Greenblatt Edward Snow is a professor of English at Rice University. North Point Press has published his translations of Rilke's New Poems (1907), New Poems (1908) [ The Other Part], The Book of Images, and Uncollected Poems . He has won both the Academy of American Poets' Harold Morton Landon Translation Award and the PEN Award for Poetry in Translation. Inside Brugel PART ONE Thinking in Images At the ledge of the window in the left foreground of Children's Games (see foldout), two faces are juxtaposed (Fig. 8). One is the round face of a tiny child who gazes wistfully off into space; the other is the mask of a scowling adult, through which an older child looks down on the scene below, perhaps hoping to frighten someone playing beneath him. Bruegel takes pains to emphasize the pairing by repeating it in the two upper windows of the central building (Fig. 9). Out of one of these, another small child dangles a long streamer and gazes at it as a breeze blows it harmlessly toward the pastoral area on the left; out of the other, an older child watches the children below, apparently waiting to drop the basket of heavy-looking objects stretched from his arm on an unfortunate passerby.At the two places in the painting that most closely approximate the elevation from which we ourselves view the scene, Bruegel has positioned images that suggest an argument about childhood. The two faces at the windowsill pose the terms of this argument in several ways at once. Most obviously, they juxtapose antithetical versions of the painting's subject: the child on the right embodies a blissful innocence, while the one on the leftmakes himself into an image of adult ugliness. But they also suggest an ironic relationship between viewer and viewed: we see a misanthropic perspective on childhood side by side with a cherubic instance of what it scowls upon. And at the level of our own engagement with the painting's images, the faces trigger opposite perceptual attitudes: one encourages us to regard appearances as innocent, the other to consider what is hidden beneath them.Interestingly enough,