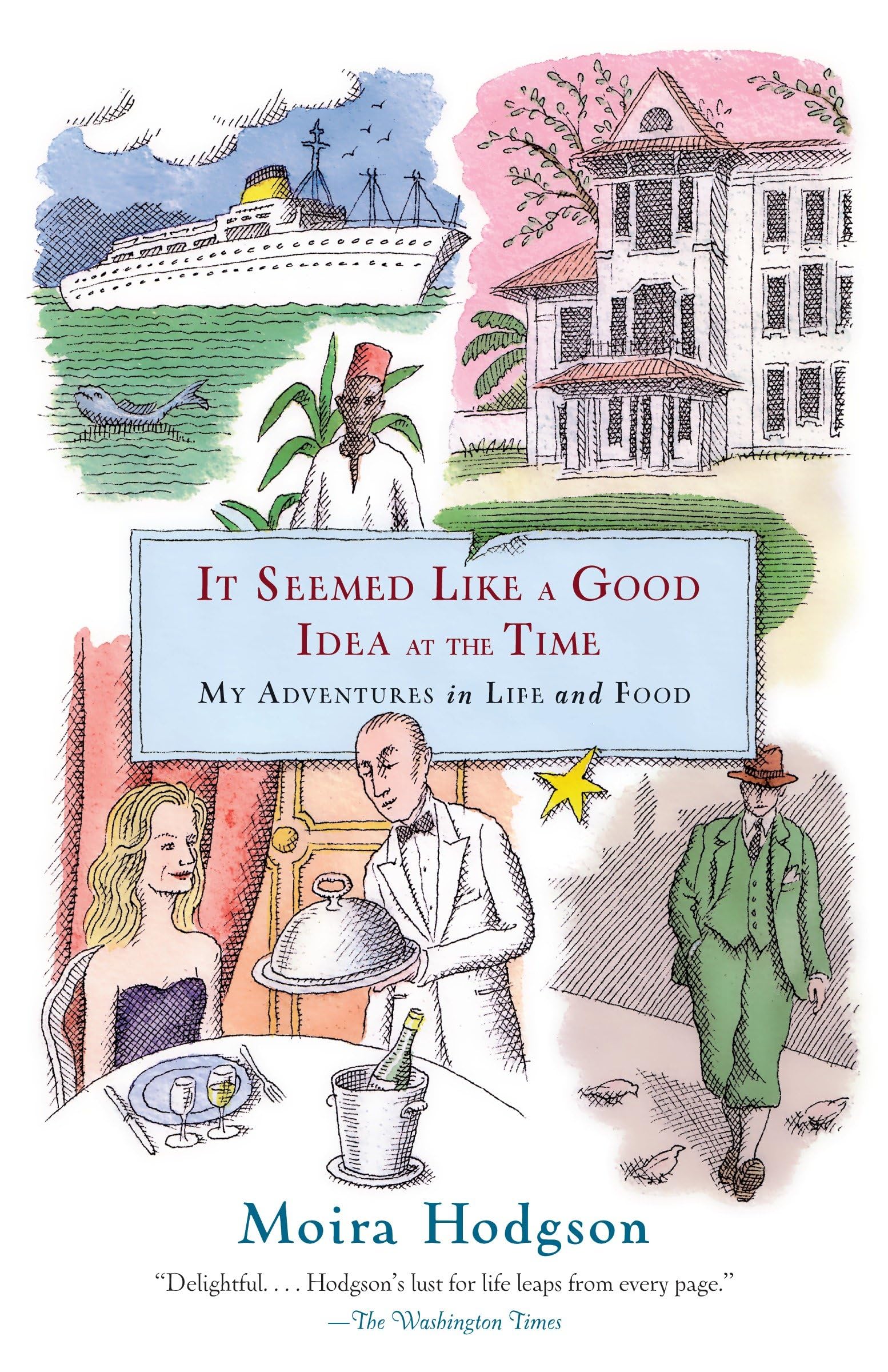

It Seemed Like a Good Idea at the Time: My Adventures in Life and Food

$16.00

by Moira Hodgson

Shop Now

The daughter of a British Foreign Service officer, Moira Hodgson spent her childhood in many a strange and exotic land. She discovered American food in Saigon, ate wild boar in Berlin, and learned how to prepare potatoes from her eccentric Irish grandmother. Today, Hodgson has a well-deserved reputation as a discerning critic whose columns in the New York Observer were devoured by dedicated food lovers for two decades. A delightful memoir of meals from around the world—complete with recipes— It Seemed Like a Good Idea at the Time reflects Hodgson’s talent for connecting her love of food and travel with the people and places in her life. Whether she’s dining on Moroccan mechoui , a whole lamb baked for a day over coals, or struggling to entertain in a tiny Greenwich Village apartment, her reminiscences are always a treat. “Delightful. . . . Hodgson’s lust for life leaps from every page.” — The Washington Times “Engaging. . . . If [Hodgson’s] thoughtful, enjoyable recollections may be said to have a theme, it is this: ‘Food for sympathy, food for love, food for keeping death at bay.’” — The Wall Street Journal “A veritable banquet of food and personality anecdotes.” —Liane Hansen, Weekend Edition Sunday , NPR “[Hodgson’s] addition to the ever-growing list of food memoirs will surprise (and probably charm). . . . Delicious.” — San Francisco Weekly Moira Hodgson was the restaurant critic for the New York Observer for two decades. She has worked on the staff of the New York Times and Vanity Fair, and is the author of several cookbooks. She lives in New York City and Connecticut. THE WAITER STOOD OVER ME, pen at the ready. "Signorina?" For lunch I ordered sardines on toast, pickled herring, a grilled mutton chop, buttered green beans, pommes lyonnaise and lemon sherbet. I was twelve, sitting with my family in the dining room of Lloyd Triestino's MV Victoria as we sailed through the Strait of Malacca, en route from Singapore to Genoa. Once again, we had packed up and were moving on. Those were the days of the great ocean liners, and my first meals out were not in restaurants, but on ships. A color reproduction of an eighteenth-century Italian Romantic painting decorated the cover of the menu. It told a story. A young woman with downcast eyes hastened across a balcony in Venice, a black veil artfully draped over her hair and shoulders to reveal her pale, comely face and low decolletage. She was holding a letter behind her as if it contained some news she couldn't bear to read. The title of the picture was Vendetta, which a translator had rendered, insipidly, "Requital." The long menu was in Italian, with an English translation on the opposite page. The words had a dramatic poetry that made my imagination soar: "jellied goose liver froth . . . Moscovite canape . . . glazed veal muscle Æ la Milanese . . . savage orange duck . . . golden supreme of swallow fish in butter . . ." And darkly: "slice of liver English-style." Because the ship docked in Bombay, Karachi and Colombo, there was also Indian food, a curry of the day described only by a town or region--Goa, Madras, Delhi--served with things I'd never heard of--pappadom, chapatti, paratha, dal and biriani. For the next three weeks, the menu changed every lunch and dinner, with a different Italian Romantic painting on its cover (always a portrait of a beautiful woman; this was an Italian ship, after all). I ticked off the dishes I ate and pasted the menus into a blue scrapbook. I am looking at it now. It opens with a display of black-and-white postcards of the long, elegant white ship, built in 1951, so different from the bloated shape of today's cruise liners. A Lloyd Triestino paper napkin signed with the names of the seven young members of the Seasick Sea Serpents Club, founded by yours truly, shares a page with a yellow matchbook stamped in red with the steamship company's far-flung continents of call: Asia, Africa and Australia. The passenger list erroneously records the family as embarking in Karachi. A brochure of useful hints advises "easy dress" for lunch and "formal attire" for dinner. The programs for the day's activities, slipped under the cabin door each morning, are also pasted onto my book's faded, dog-eared pages, their covers printed with commedia dell'arte figures: Pierrot, Columbine, Harlequin and clowns, one of them with a red nose, holding out a tumbler of wine. There were concerts by the ship's orchestra (as many as four a day), fancy dress balls and bartender Carlo's special cocktails, such as gin with lemon and green Chartreuse. I also glued in brochures of the places we visited when the ship docked in a port of call: a "luxury" coach tour of Bombay (where I saw vultures circling funeral pyres that burned behind high walls) and a sleepy Italian fishing village called Portofino "for people seeking rest and quiet." Pink and orange tickets to horsey horsey and tombola make a collage with the ship's airmail envelopes an