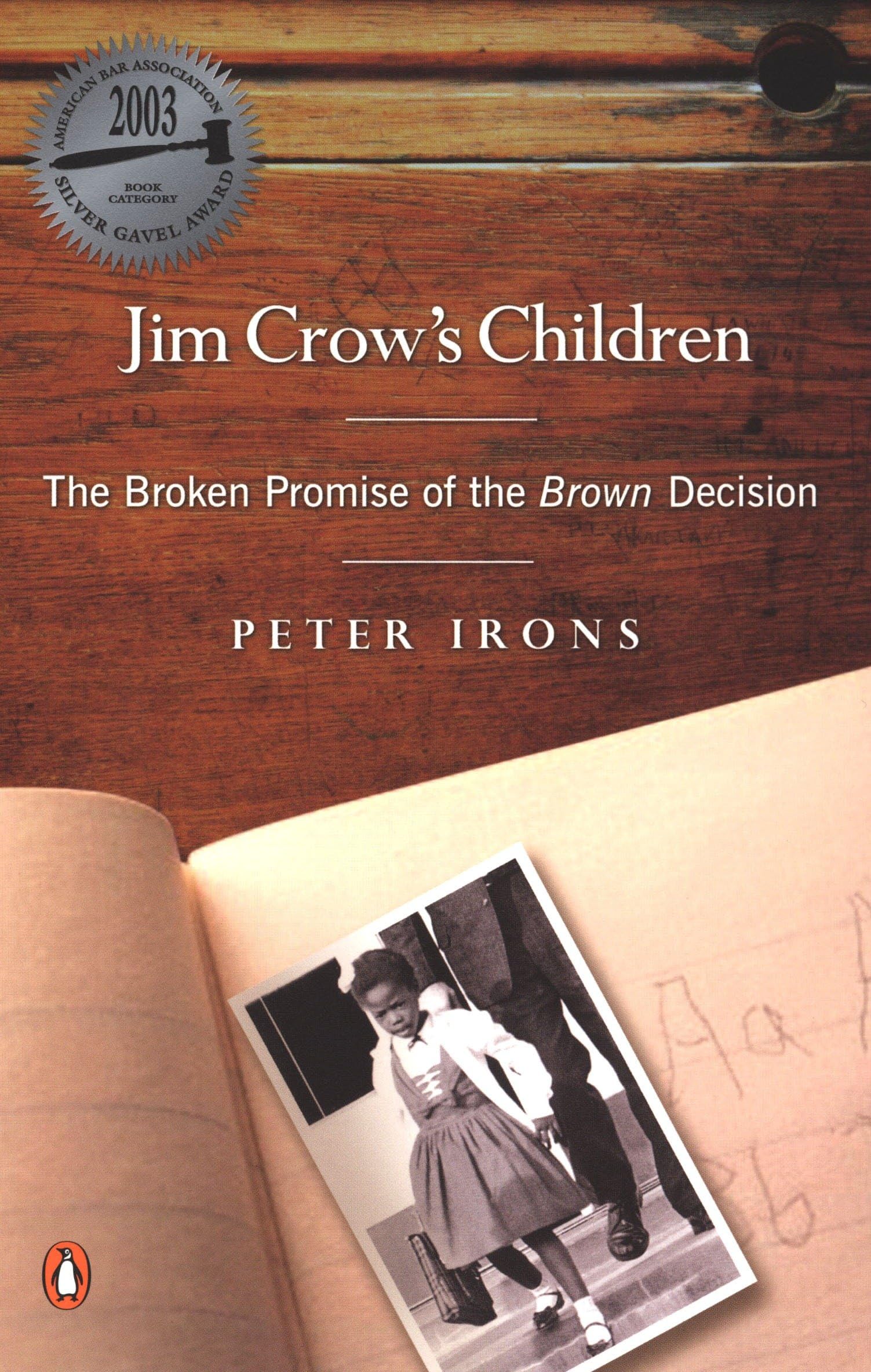

Peter Irons, acclaimed historian and author of A People History of the Supreme Court , explores of one of the supreme court's most important decisions and its disappointing aftermath In 1954 the U.S. Supreme Court sounded the death knell for school segregation with its decision in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka. So goes the conventional wisdom. Weaving together vivid portraits of lawyers and such judges as Thurgood Marshall and Earl Warren, sketches of numerous black children throughout history whose parents joined lawsuits against Jim Crow schools, and gripping courtroom drama scenes, Irons shows how the erosion of the Brown decision—especially by the Court’s rulings over the past three decades—has led to the “resegregation” of public education in America. "A book of sorrows—and of surpassing importance." -- Kirkus Reviews "Underscoring the long history of educational inequality that led to Brown v. Board, Irons argues that the quality and outcome of the public education currently offered to blacks are both still shaped by the enduring influence of Jim Crow laws and schools." -- The New York Times Peter Irons is emeritus professor of political science at the University of California, San Diego. He is the author of five previous award-winning books. The most recent, A People's History of the Supreme Court , was awarded the Silver Gavel Certificate of Merit by the American Bar Association. His work has also been published in numerous law reviews and presitigious journals. In addition to his extensive academic contributions, Irons has also been very active in public affairs. For example, he was elected to two terms on the national board of the American Civil Liberties Union and was a practicing civil rights and liberties attorney. In the latter role, he notably served as lead counsel in the successful effort to reverse the World War Two criminal convictions of Japanese-Americans who challenged the curfew and relocation orders. Chapter 1 "Cut Yer Thumb er Finger Off" "None of us niggers never knowed nothin' 'bout readin' and writin'. Dere warn't no school for niggers den, and I ain't never been to school a day in my life. Niggers was more skeered of newspapers dan dey is of snakes now, and us never knowed what a Bible was dem days." These are the words of Georgia Baker about her life as a slave, growing up on a Georgia plantation before the Civil War. Both the land and her body were owned by Alexander H. Stephens, a planter who became vice-president of the Confederate States of America. Like most black people who were born into slavery, Georgia was illiterate, because it was both illegal and dangerous for a slave to learn how to read and write in the days before Emancipation. Arnold Gragston told of his master in Macon County, Kentucky. "Mr. Tabb was a pretty good man," Arnold said. "He used to beat us, sure; but not nearly so much as others did." When the master suspected that his slaves were learning to read and write, he would call them to the "big house" and grill them. "If we told him we had been learnin' to read," Arnold recounted, "he would near beat the daylights out of us." Sarah Benjamin, who was born on a Louisiana plantation, recalled the fate of fellow slaves whose masters discovered that their "property" had secretly learned to read and write: "If yer learned to write dey would cut yer thumb er finger off." But some slaves took the risk of beatings or amputations. Mandy Jones described the way that slaves in Mississippi would educate themselves. "Dey would dig pits, and kiver the spot wid bushes an' vines," he said. "Way out in de woods, dey was woods den, an' de slaves would slip out of de Quarters at night, an' go to dese pits, an' some niggah dat had some learnin' would have a school." But not all learning took place in "pit schools" in the woods. The children of slave owners sometimes became the teachers of slave children. "De way de cullud folks would learn to read was from de white chillun," Mandy Jones recalled. "De white chilluns thought a heap of de cullud chilluns, an' when dey come out o' school wid deir books in deir han's dey take de cullud chilluns, and slip off somewhere an' learns de cullud chilluns deir lessons, what deir teacher has jes' learned dem." Too much learning, however, could give a slave the tools to escape from bondage. William Johnson told the story of a "smart slave" on his Virginia plantation, a coachman named Joe Sutherland. "Joe always hung around the courthouse with master," William said. "He went on business trips with him, and through this way, Joe learned to read and write unbeknownst to master. In fact, Joe got so good that he learned how to write passes for the slaves. Master's son, Carter Johnson, was clerk of the county court, and by going around the court every day Joe forged the county seal on these passes and several slaves used them to escape to free states." But Joe was betrayed by another slave, William said, "and Joe was put in shac