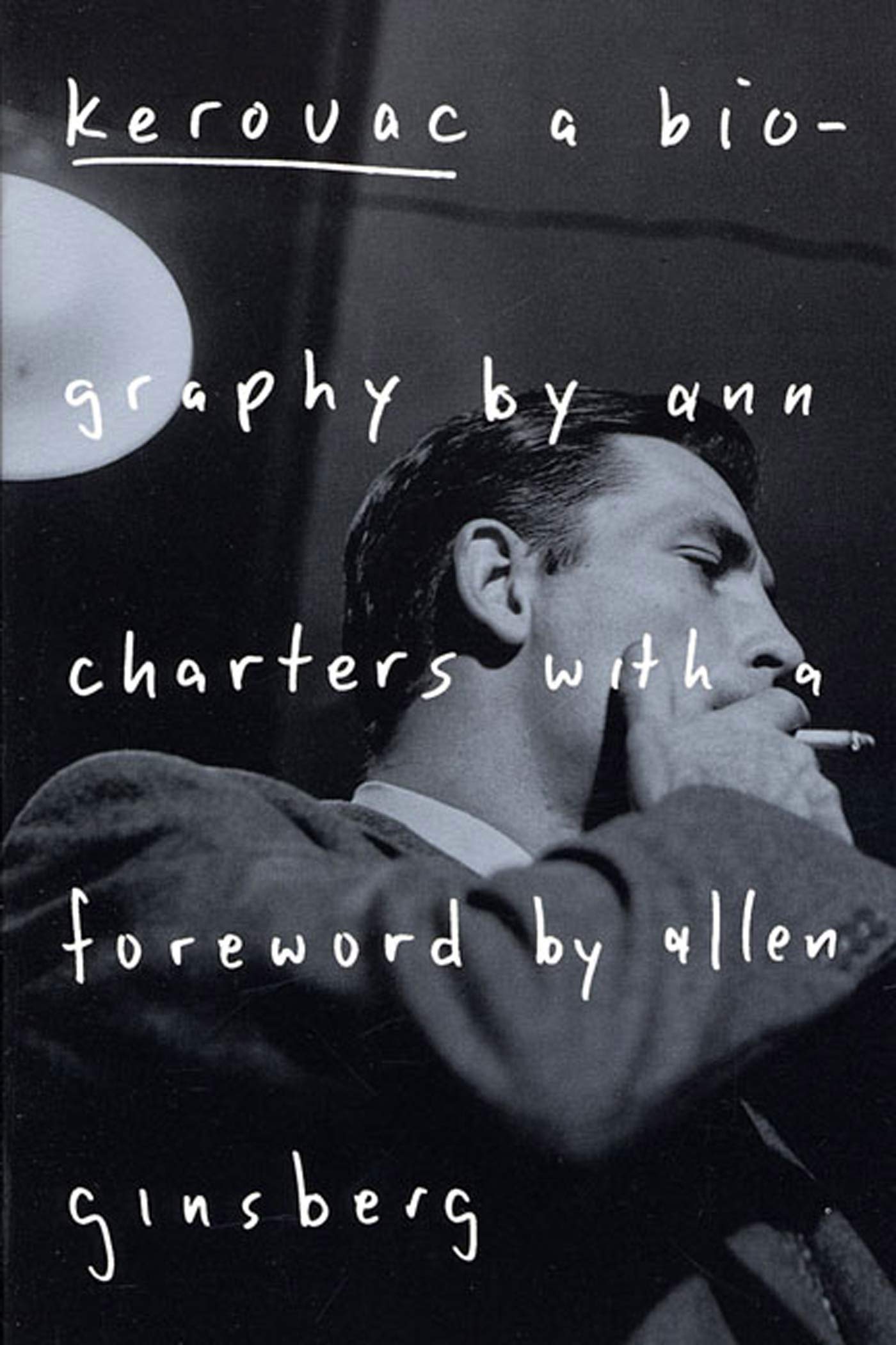

Now that Kerouac's major novel, On the Road is accepted as an American classic, academic critics are slowly beginning to catch up with his experimental literary methods and examine the dozen books comprising what he called 'the legend of Duluoz.' Nearly all of his books have been in print internationally since his death in 1969, and his writing has been discovered and enjoyed by new readers throughout the world. Kerouac's view of the promise of America, the seductive and lovely vision of the beckoning open spaces of our continent, has never been expressed better by subsequent writers, perhaps because Kerouac was our last writer to believe in America's promise--and essential innocence--as the legacy he would explore in his autobiographical fiction. “It is about men and ideas that changed everything. That's reason enough to read it.” ― The New York Times “This biography becomes almost a novel in itself. The darkly intense, handsome young man, the gypsy wanderer, hero and prophet to everyone but himself...Written with a beautiful combination of toughness and love, of daring insight and honesty, it is a worthy monument to a troubled man.” ― The Los Angeles Times “Behind the 'crazy rebel' of the novels who inspired a whole generation to go hitchhiking across America in search of 'the myth of the rainy night' lay a life of insecurity and wretched loneliness...a duality perceptively illustrated by Ann Charters in her lucid, well-researched biography.” ― The Sunday Telegraph Now that Kerouac's major novel, On the Road is accepted as an American classic, academic critics are slowly beginning to catch up with his experimental literary methods and examine the dozen books comprising what he called 'the legend of Duluoz.' Nearly all of his books have been in print internationally since his death in 1969, and his writing has been discovered and enjoyed by new readers throughout the world. Kerouac's view of the promise of America, the seductive and lovely vision of the beckoning open spaces of our continent, has never been expressed better by subsequent writers, perhaps because Kerouac was our last writer to believe in America's promise--and essential innocence--as the legacy he would explore in his autobiographical fiction. Ann Charters received her B.A. at Berkeley and her Ph.D. at Columbia. She first met Kerouac at a poetry reading in Berkeley in 1956, and compiled a comprehensive bibliography of his work in 1967. A professor of English at the University of Connecticut, she is also the editor of Selected Letters of Jack Kerouac and the Portable Kerouac Reader , and the author of Beats and Company: Portrait of a Literary Generation . Kerouac A Biography By Ann Charters St. Martin's Press Copyright © 1974 Ann Charters All rights reserved. ISBN: 978-0-312-11347-6 Contents Title Page, Foreword by Allen Ginsberg, Preface, Introduction, Part One, 1922-1951, Part Two, 1951-1957, Part Three, 1957-1969, Appendices:, One: Chronology, Two: Notes & Sources, Three: Bibliographical Chronology, Four: Identity Key, Five: Index, Also by Ann Charters, Copyright, CHAPTER 1 In 1954, when Jack Kerouac was thirty-two years old, he tried to define, for a friend, what it was he wanted out of life. The friend suggested that what he really wanted was a thatched hut like Thoreau's, not at Walden Pond, but in Lowell, the town where Jack was born, near Walden, in Massachusetts. Kerouac agreed. He had left Lowell after high school, but, emotionally, he never left it at all, and whatever it was that held him there was always with him. No one completely outgrows his childhood and everyone tends to sentimentalize the place where he grew up, but Lowell is not a town that's easy to feel sentimental about. It is an old Massachusetts mill-town, not Thoreau's Concord or Walden Pond. Yet Kerouac's attachment to Lowell, like so many other things in his life, was dominated by fantasy, as much as by anything real. Through most of his life Kerouac played games with himself, giving himself new roles and identities, vanities as he called them in his last years. His belief in himself as a writer was his main identity, and in an essential way after he left Lowell it was the only identity that held him fast. Neal Cassady once imagined a mutual friend saying of Jack: "Where is this guy, Kerouac, anyway?" Kerouac himself never knew. His essence lay in a romantic vision of himself. It lay in his fantasies: as a child, the fantasy of living with a saintly older brother Gerard; as an adolescent, of fighting evil alongside the mysterious Doctor Sax, of going with a football scholarship from a small high school to All-America fame at an Ivy League college; then, as an adult, the fantasy of being the greatest writer in the English language since Shakespeare and James Joyce, and when that success didn't come, in desperation, successive fantasies of being a drifter, a railroad brakeman, a Zen mountaineer, a holy mystic li