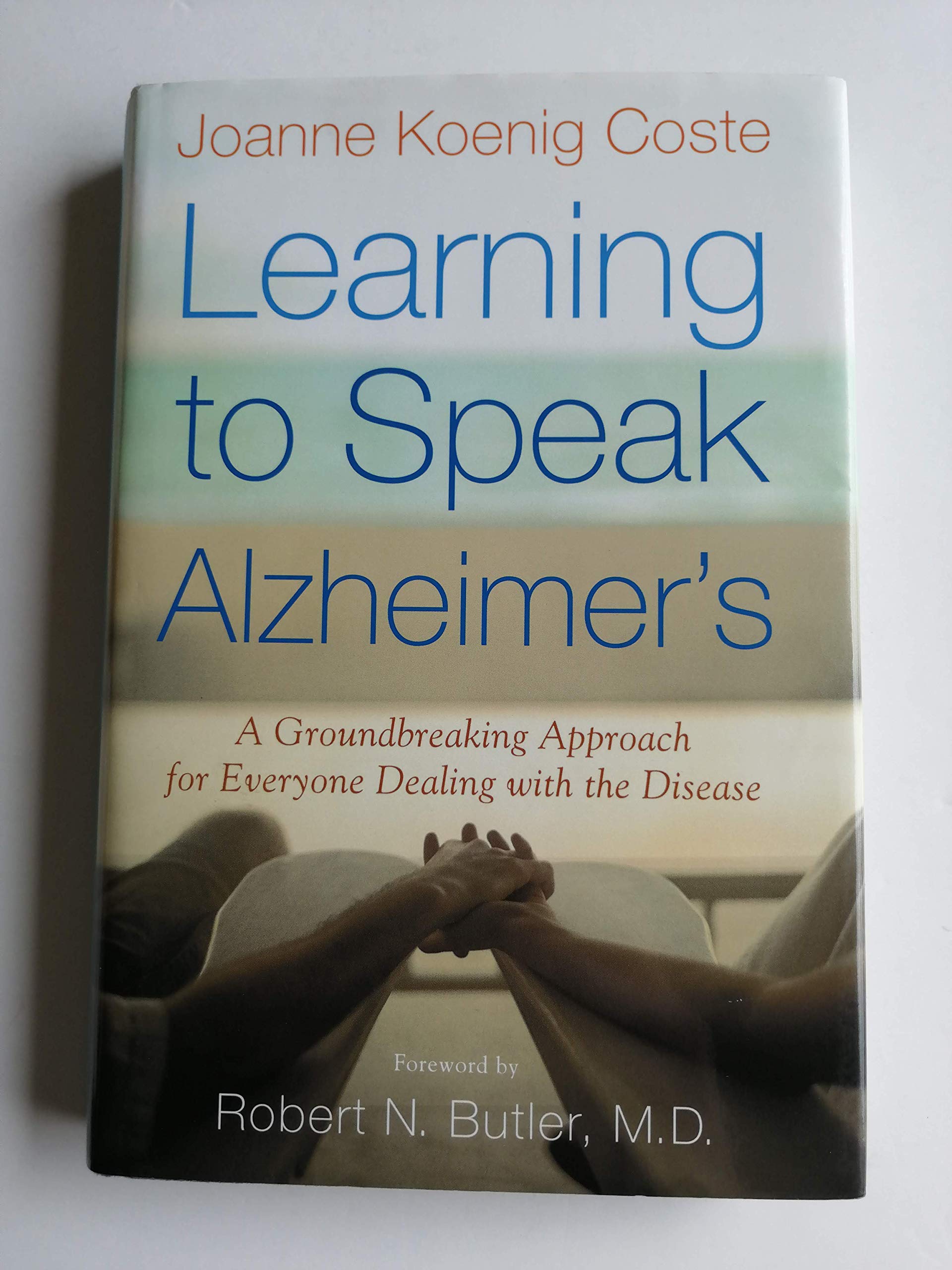

Learning to Speak Alzheimer's: A Groundbreaking Approach for Everyone Dealing With the Disease

$16.04

by Joanne Koenig Coste

Shop Now

A pioneer in the care and treatment of Alzheimer's introdcues her groundbreaking approach to dealing with the disease, offering a five step approach to caring for people with progressive dementia while offering hundreds of practical tips that can make less threatening. "A fine addition to Alzheimer's and caregiving collections." -- Review Joanne Koenig Coste, a nationally recognized expert and an outspoken advocate for patient and family care, is a board member of the American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease. Currently in private practice as an Alzheimer’s family therapist, Koenig Coste also serves as president of Alzheimer’s Consulting Associates. She lectures around the country and is the recipient of a National Award for Health Heroes from Reader’s Digest. She was named a “Woman to Watch in the 21st Century” by NBC Nightly News 1 The Ticking Meter My head feels like an old depot, worn by time and tears. No more locomotives passing through, café filled with tales and baggage. The old depot"s barren now. There has been a great brain robbery. One cool spring day in 1971, the kind that makes New Englanders smile at each other, I was driving with my husband down the main street of a small coastal town south of Boston. I spotted a parking space in front of our destination, a café where we dined frequently, sharing chowder, fried clams, gigantic iced teas, and dreams of the future. I told my husband, "Look, there"s a parking space. Not only that — there"s money in the meter." "I"m glad," he murmured, seeking my eyes through his sunglasses. "But I think my meter is running out." His metaphor fell on deaf ears. With a new life growing inside me — our fourth child — I may have been unwilling to accept his meaning. At the time my husband"s lapses in memory seemed innocuous. He might forget a neighbor"s name or neglect to stop at the store or forget where the ignition was in the car, but I was clever at disregarding the hints of medical illness. After all, he frequently drove different cars as part of his advertising business, and he was so busy; keeping up with minor details was too much to expect. The situation will improve when we move into a new house, I told myself, or when the children are older, or when someone in the medical community will listen to what I am saying. We moved, the children grew, and the improvement never happened. We were near financial ruin. Customers weren"t calling us back; new jobs weren"t coming our way. He had ever greater difficulty focusing and organizing his thoughts, sometimes rewriting ad copy he had finished the day before. Once so gentle, docile, and fun to be around, he became frustrated and angry. My mantra continued whenever I was awake: "Things will be so much better when —" When? Our journey into the world of dementia began in 1971, when no guideposts, advocates, manuals, or support groups were available to help us. The National Alzheimer"s Association would not be organized for another decade. My husband was only in his forties, and I did not believe that his forgetfulness was a natural part of aging. The children chided their father occasionally about his "absent-mindedness" but seemed to see nothing deeper. The prescription for Valium to treat his supposed "depression" was refilled many times. And sometimes my husband unwittingly doubled the dose or forgot to take it at all. Always well dressed in the past, my handsome, athletic husband began to need help matching his suit, tie, and shirt. I started to lay out his clothes for the next day before we went to bed at night. I made sure to tell him what fun I had selecting the outfits, but I was embarrassed to be doing this task. I never mentioned it to others. Then in 1973, a major stroke paralyzed him on one side, and I replaced the Brooks Brothers suits with sweatsuits, which he soon stained with food. The stroke took away his language ability, transforming a man who had made his living through eloquent writing into someone who had to rely entirely on words of one syllable. Neurologists and physical therapists told me not to expect any improvements in his speech though he did learn to walk again, ever so slowly, with a leg brace and a walker. Life was very hard for all of us, but it was especially horrible for my husband. He became frustrated beyond comprehension. At times he did not seem to recognize our children or me. Sometimes he appeared thoroughly perplexed about our home. I remember him angrily rattling the doorknob in an effort to go outside but not being able to open the door. And yet I also recall his having enough of his former self that when he looked at our young baby, tears would run down his face. His abilities continued to decline. As soon as I became the least bit comfortable with his current condition, he would take another step in the downhill progression of dementia. I felt completely overwhelmed. At times I was diapering both our younge