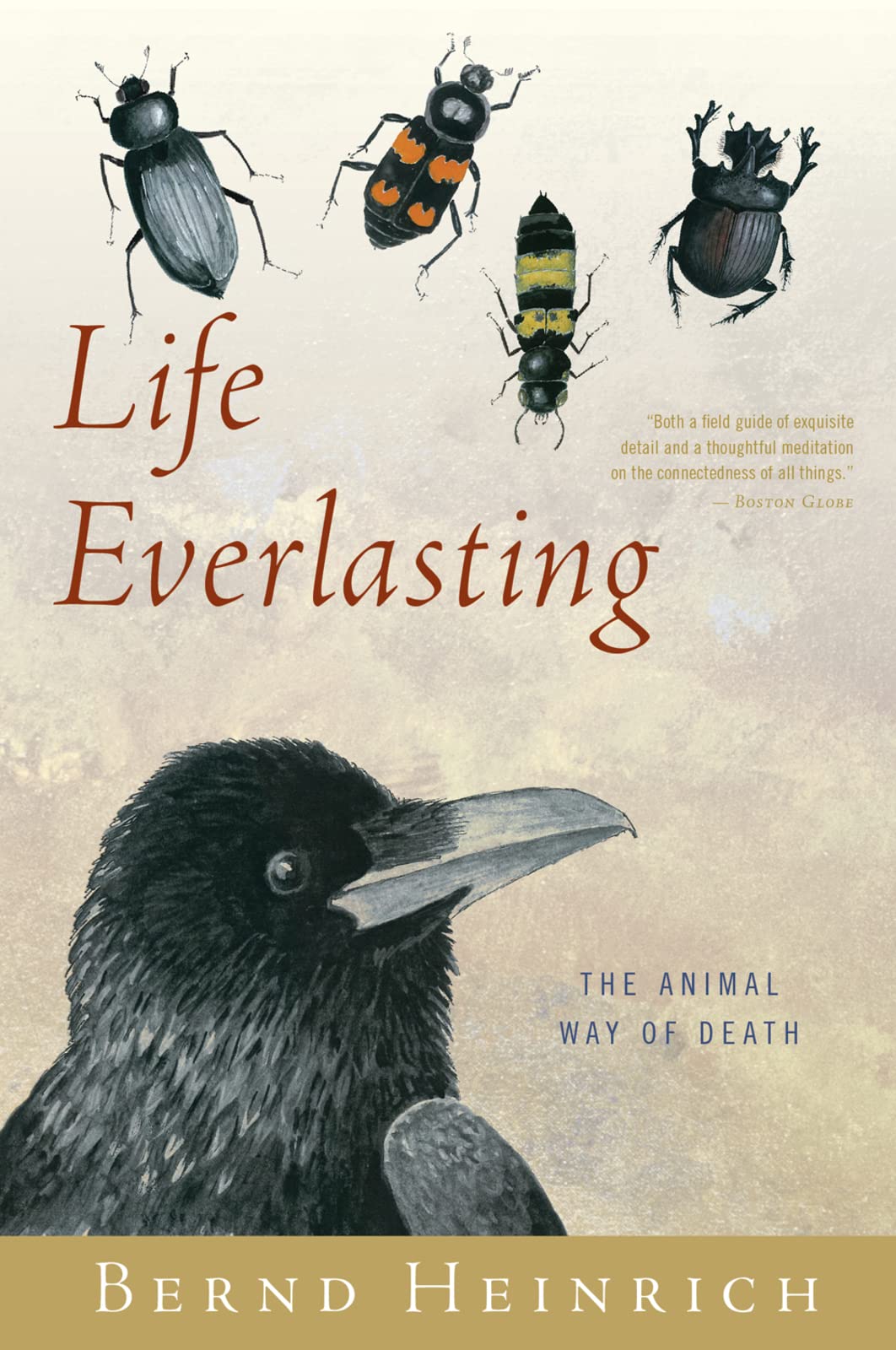

From one of the finest naturalists and writers of our time, a fascinating investigation of Nature’s inspiring death-to-life cycle. How does the animal world deal with death? And what ecological and spiritual lessons can we learn from examining this? Bernd Heinrich has long been fascinated by these questions, and when a good friend with a terminal illness asked if he might have his “green burial” at Heinrich’s hunting camp in Maine, it inspired the acclaimed biologist and author to investigate. Life Everlasting is the fruit of those investigations, illuminating what happens to animals great and small after death. From beetles to bald eagles, ravens to wolves, Heinrich reveals the fascinating and mostly hidden post-death world that occurs around us constantly, while examining the ancient and important role we too play as scavengers, connecting death to life. “Bernd Heinrich is one of the finest naturalists of our time. Life Everlasting shines with the authenticity and originality that are unique to a life devoted to natural history in the field.”—Edward O. Wilson, author of The Future of Life and The Social Conquest of Earth "Despite focusing on death and decay, Life Everlasting is far from morbid; instead, it is life-affirming . . . convincing the reader that physical demise is not an end to life, but an opportunity for renewal."— Nature “A worldwide tour of the role of death in nature that is consistently fascinating and fun to read.”— Seattle Times BERND HEINRICH is an acclaimed scientist and the author of numerous books, including the best-selling Winter World, Mind of the Raven, Why We Run, The Homing Instinct, and One Wild Bird at a Time. Among Heinrich's many honors is the 2013 PEN New England Award in nonfiction for Life Everlasting. He resides in Maine. INTRODUCTION If you would know the secret of death you must seek it in the heart of life. — Kahlil Gibran, The Prophet . . . . Earth’s the right place for love; I don’t know where it’s likely to go better. — Robert Frost, “Birches” Yo, Bernd — I’ve been diagnosed with a severe illness and am trying to get my final disposition arranged in case I drop sooner than I hoped. I want a green burial — not any burial at all — because human burial is today an alien approach to death. Like any good ecologist, I regard death as changing into other kinds of life. Death is, among other things, also a wild celebration of renewal, with our substance hosting the party. In the wild, animals lie where they die, thus placing them into the scavenger loop. The upshot is that the highly concentrated animal nutrients get spread over the land, by the exodus of flies, beetles, etc. Burial, on the other hand, seals you in a hole. To deprive the natural world of human nutrient, given a population of 6.5 billion, is to starve the Earth, which is the consequence of casket burial, an internment. Cremation is not an option, given the buildup of greenhouse gases, and considering the amount of fuel it takes for the three-hour process of burning a body. Anyhow, the upshot is, one of the options is burial on private property. You can probably guess what’s coming . . . What are your thoughts on having an old friend as a permanent resident at the camp? I feel great at the moment, never better in my life in fact. But it’s always later than you think. This letter from a friend and colleague compelled me toward a subject I have long found fascinating: the web of life and death and our relationship to it. At the same time, the letter made me think about our human role in the scheme of nature on both the global and the local level. The “camp” referred to is on forest land I own in the mountains of western Maine. My friend had visited me there some years earlier to write an article on my research, which was then mostly with insects, especially bumblebees but also caterpillars, moths, butterflies, and in the last three decades, ravens. I think it was my studies of ravens, sometimes referred to as the “northern vultures,” that may have motivated him to write me. The ravens around my camp scavenged and recycled hundreds of animal carcasses that friends, colleagues, and I provided for them there. My friend knows we share a vision of our mortal remains continuing “on the wing.” We like to imagine our afterlives riding through the skies on the wings of birds such as ravens and vultures, who are some of the more charismatic of nature’s undertakers. The dead animals they disassemble and spread around are then reconstituted into all sorts of other amazing life throughout the ecosystem. This physical reality of nature is for both of us not only a romantic ideal but also a real link to place that has personal meaning. Ecologically speaking, this vision also involves plants, which makes our human role global as well. The science of ecology/biology links us to the web of life. We are a literal part of the creation, not some afterthought — a revelation