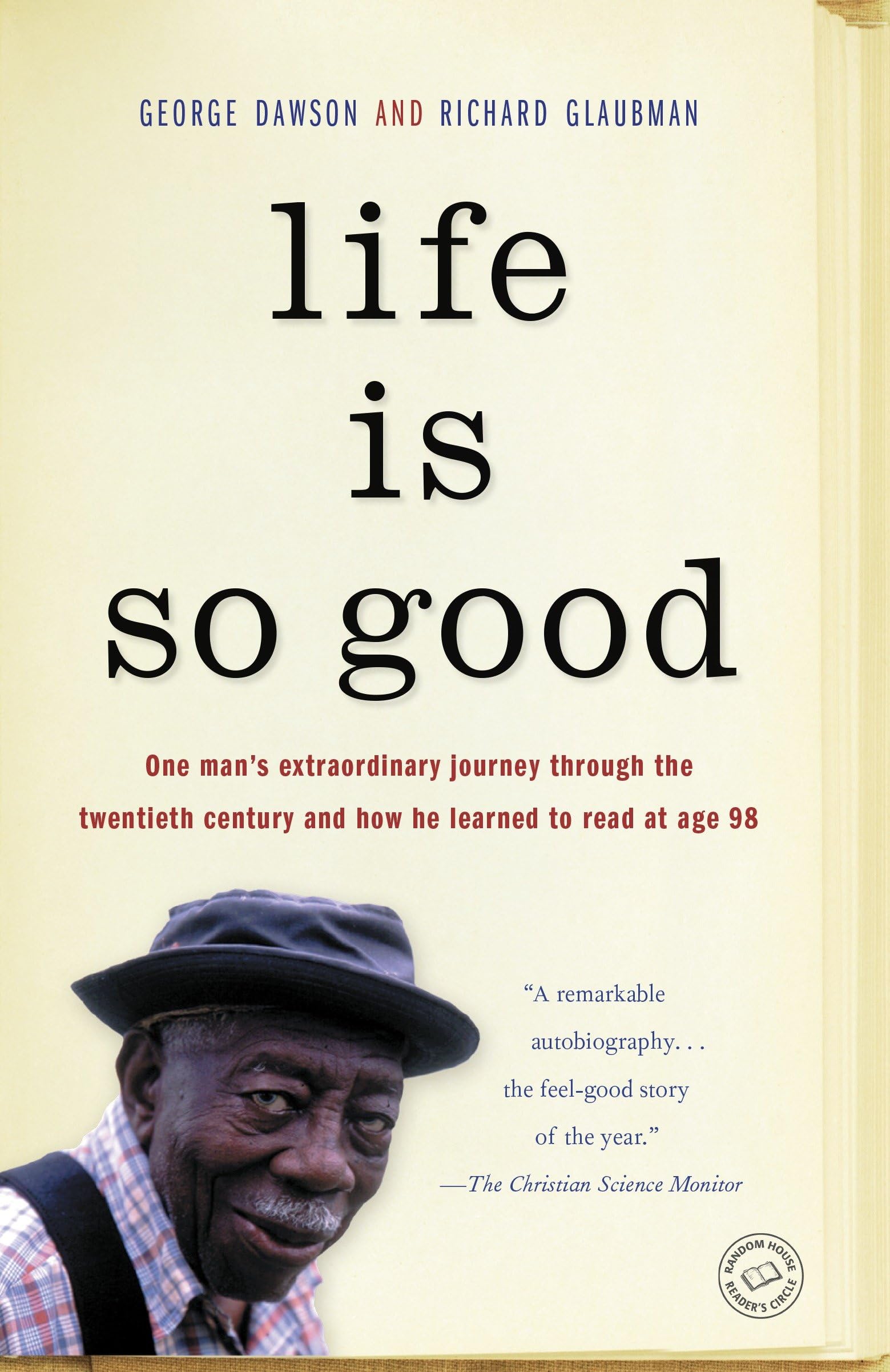

One man’s extraordinary journey through the twentieth century and how he learned to read at age 98 “Things will be all right. People need to hear that. Life is good, just as it is. There isn’t anything I would change about my life.”—George Dawson In this remarkable book, George Dawson, a slave’s grandson who learned to read at age 98 and lived to the age of 103, reflects on his life and shares valuable lessons in living, as well as a fresh, firsthand view of America during the entire sweep of the twentieth century. Richard Glaubman captures Dawson’s irresistible voice and view of the world, offering insights into humanity, history, hardships, and happiness. From segregation and civil rights, to the wars and the presidents, to defining moments in history, George Dawson’s description and assessment of the last century inspires readers with the message that has sustained him through it all: “Life is so good. I do believe it’s getting better.” WINNER OF THE CHRISTOPHER AWARD “A remarkable autobiography . . . . the feel-good story of the year.”— The Christian Science Monitor “A testament to the power of perseverance.”— USA Today “ Life Is So Good is about character, soul and spirit. . . . The pride in standing his ground is matched—maybe even exceeded—by the accomplishment of [George Dawson’s] hard-won education.”— The Washington Post “Eloquent . . . engrossing . . . an astonishing and unforgettable memoir.”— Publishers Weekly Look for special features inside. Join the Circle for author chats and more. “A remarkable autobiography . . . . the feel-good story of the year.”— The Christian Science Monitor “A testament to the power of perseverance.”— USA Today “ Life Is So Good is about character, soul and spirit. . . . The pride in standing his ground is matched—maybe even exceeded—by the accomplishment of [George Dawson’s] hard-won education.”— The Washington Post “Eloquent . . . engrossing . . . an astonishing and unforgettable memoir.”— Publishers Weekly George Dawson lives in Dallas, Texas. Richard Glaubman is an elementary school teacher. He lives outside Seattle, Washington. Wanting to enjoy every moment, I stared at the hard candies in the different wooden barrels. The man behind the counter was white. I could tell he didn't like me, so I let him see the penny in my hand. "Take your time, son," my father said with a grin. "You did a man's work this year." Putting his hand on my shoulder, he said to the store clerk, "He's all of ten years, but the boy crushed as much cane as I did." Since the age of four, I had always been working to help the family. I don't know if it was pride from Father's words or the pleasure from a piece of hard candy that beckoned, but I felt so good I thought I would burst. I had been thinking of those hard candies since my father woke me before daybreak and said, "Hitch the wagon. We gonna take some ribbon syrup into town and you comin'." When I went back inside, the stove was going and Ma had a pot of mush cooling. We ate quiet-like so as not to wake the little ones that were asleep on the other side of the room. I was happy to see they was still sleeping for it was uncommon to spend the day alone with my father. We never had much time to talk and I just liked to be with him. Two barrels of cane syrup were tied down in the wagon. We sat up front. My father clucked toward the mule. I wanted to tell him that I was glad he was taking me and it was going to be just him and me together all day. Trouble was, I didn't know how to say that in words. So under the shadow of my straw hat, I just looked over at him. Solid is what I would say. He took care of us. We had potatoes and carrots buried in the straw and salt pork hangin' from the rafters. We was free of worries. Papa was a good provider. Someday I would be just like him. Must have been a couple of hours toward town when my father nudged me. He handed me the reins and unwrapped some burlap. I took a piece of cornbread with a big dab of lard on it. When I commenced to eat, he started talking. "With this ribbon syrup, we be out of debt and have some left for trading. We gonna have seeds for cotton, some new banty chicks, and the fruit trees that are gonna bear fruit next year. No one has the fever and we all be healthy. "Life is good." And with a grin, he added, "I do believe it's getting better." I liked it when Papa talked to me as a man. The morning haze had long ago burned off. The wagon stirred up a lot of dust that kind of settled over everything in a nice, smooth blanket. It was good for the mule as the dust had a way of keeping the flies off. Nothing else was said for the next hour, till we came around the last stand of trees and to the rise above Marshall. In those days, I had in my mind that Marshall was maybe about the biggest and the best place there could ever be. The hardware store had big windows that I liked to look