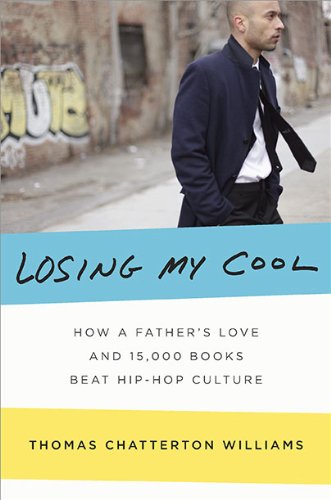

Losing My Cool: How a Father's Love and 15,000 Books Beat Hip-hop Culture

$21.99

by Thomas Chatterton Williams

Shop Now

A pitch-perfect account of how hip-hop culture drew in the author and how his father drew him out again-with love, perseverance, and fifteen thousand books. Into Williams's childhood home-a one-story ranch house-his father crammed more books than the local library could hold. "Pappy" used some of these volumes to run an academic prep service; the rest he used in his unending pursuit of wisdom. His son's pursuits were quite different-"money, hoes, and clothes." The teenage Williams wore Medusa- faced Versace sunglasses and a hefty gold medallion, dumbed down and thugged up his speech, and did whatever else he could to fit into the intoxicating hip-hop culture that surrounded him. Like all his friends, he knew exactly where he was the day Biggie Smalls died, he could recite the lyrics to any Nas or Tupac song, and he kept his woman in line, with force if necessary. But Pappy, who grew up in the segregated South and hid in closets so he could read Aesop and Plato, had a different destiny in mind for his son. For years, Williams managed to juggle two disparate lifestyles- "keeping it real" in his friends' eyes and studying for the SATs under his father's strict tutelage. As college approached and the stakes of the thug lifestyle escalated, the revolving door between Williams's street life and home life threatened to spin out of control. Ultimately, Williams would have to decide between hip-hop and his future. Would he choose "street dreams" or a radically different dream- the one Martin Luther King spoke of or the one Pappy held out to him now? Williams is the first of his generation to measure the seductive power of hip-hop against its restrictive worldview, which ultimately leaves those who live it powerless. Losing My Cool portrays the allure and the danger of hip-hop culture like no book has before. Even more remarkably, Williams evokes the subtle salvation that literature offers and recounts with breathtaking clarity a burgeoning bond between father and son. Watch a Video Thomas Chatterton Williams's Playlist Inspired by Losing My Cool Listen to Thomas Chatterton Williams 's annotated playlist , a lineup of ten essential hip-hop tracks that informed Losing My Cool , including highlights from Dr. Dre, 2pac, and Jay-Z. Browse the playlist A Conversation with Thomas Chatterton Williams Q: Tell us a little bit about yourself. I grew up in New Jersey, but my parents are from out west. They moved the family to New Jersey when my father, a sociologist by training, took a job in Newark running anti-poverty programs for the Episcopal Archdiocese. My father “Pappy” who is black, is from Galveston and Fort Worth, Texas. My mother, who is white, is from San Diego. They both lament the decision to move east. I spent the first year of my life in Newark, but was raised in Fanwood, a solidly middle-class suburb with a white side and a black side. We lived on the white side of town mainly because Pappy, who had grown up under formal segregation, refused out of principle to ever again let anyone tell him where to live. I studied philosophy at Georgetown University in Washington D.C., and more recently, attended graduate school at New York University. Q: Why did you write this book? I started writing this book out of a searing sense of frustration. It was 2007, hip-hop had sunk to new depths with outrageously ignorant artists like the Dip Set and Soulja Boy dominating the culture and airwaves, and something inside me just snapped. I was in grad school at NYU and one of my teachers gave the class the assignment of writing an op-ed article on a topic of choice, the only requirement being to take a strong stand. I went straight from class to the library and in three or four hours banged out a heartfelt 1000 words against what I saw as the debasement of black culture in the hip-hop era. After some revisions, the Washington Post published what I had written and it generated a lot of passionate feedback, both for and against. I realized that there was a serious conversation to be had on this subject and that there was a lot more that I wanted to say besides. That was why I started. By the time I finished writing, though, it had become something quite different, something very personal, a tribute to my father and to previous generations of black men and women who went through unimaginable circumstances and despite that, or rather because of it, would be ashamed of the things we as a culture now preoccupy ourselves with, rap about, and do on a daily basis. Basically, the book began as a Dear John letter to my peers and ended as a love letter to my father. Q: You fully embraced the black culture of BET and rap superstars starting at a young age. What drew you in? I think I was drawn to black culture by the same things that have been drawing the entire world to it since the days of Richard Wright, Josephine Baker and Louis Armstrong. This culture is original, potent and seductive. As we a