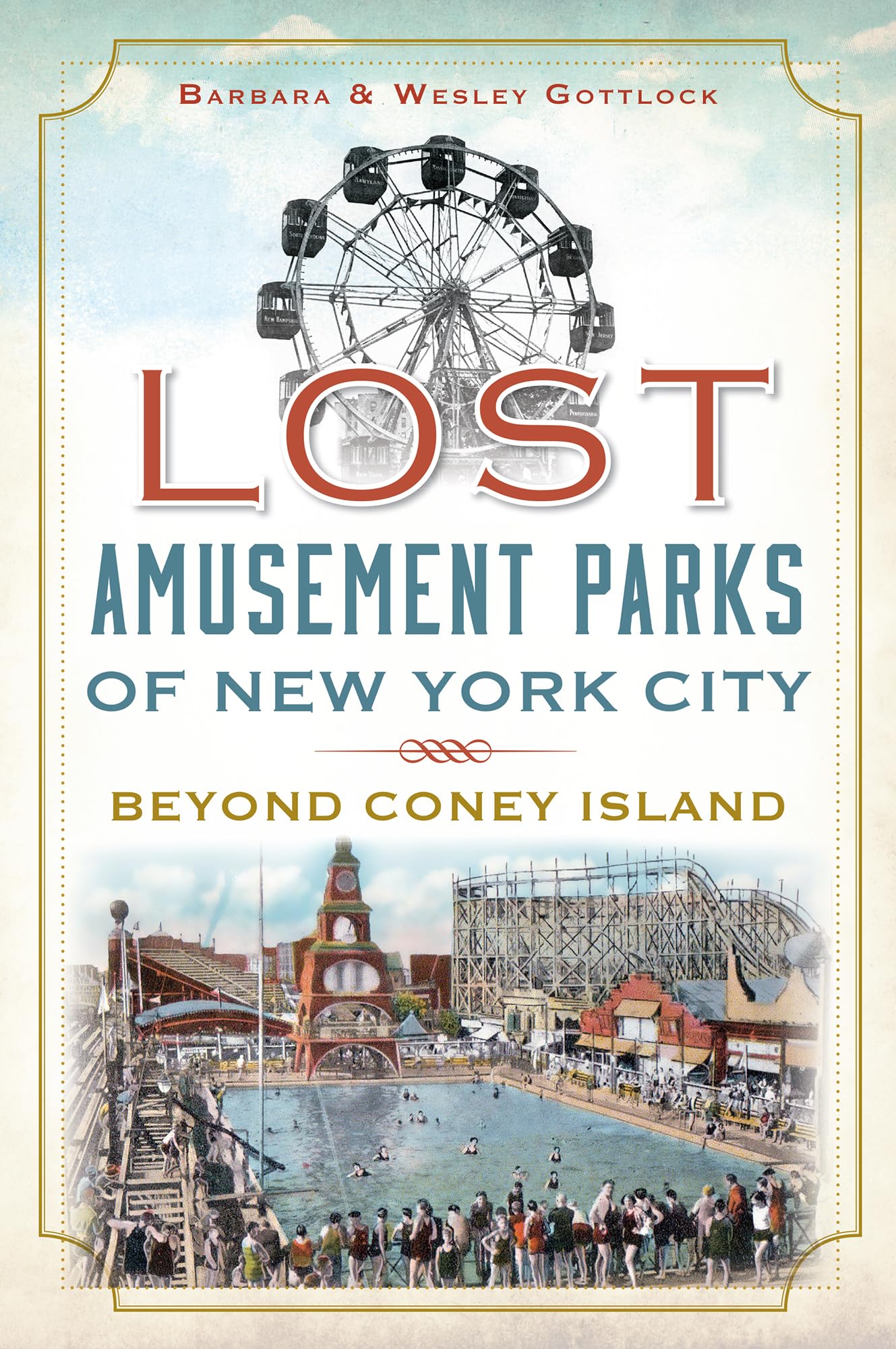

Still a relief from everyday life, theme parks are popular now. Rediscover the thrills of the past from the lost amusement parks of New York City. Coney Island is an iconic symbol of turn-of-the-century New York, but many other amusement parks thrilled the residents of the five boroughs. Strategically placed at the end of trolley lines, railways, public beaches and waterways, these playgrounds for rich and poor alike first appeared in 1767. From humble beginnings, they developed into huge sites like Fort George, Manhattan's massive amusement complex. Each park was influenced by the culture and eclectic tastes of its owners and patrons--from the wooden coasters at Staten Island's Midland Beach to beer gardens on Queens' North Beach and fireworks blasting from the Bronx's Starlight Park. However, as real estate became more valuable, these parks disappeared. Rediscover the thrills of the past from the lost amusement parks of New York City. Wesley Gottlock is a retired educator with a passion for the history of New York City and the Hudson Valley. He and his wife lecture on local history and coordinate tours to Bannerman Island in the Hudson River. This is their fifth book on New York history. Visit GottlockBooks.com to learn more. Barbara Gottlock is a retired educator who now lectures on New York history and coordinates tours to Bannerman Island in the Hudson River with her husband. This is her fifth book authored with her husband devoted to capturing New York's past. Visit their website at GottlockBooks.com. Lost Amusement Parks of New York City Beyond Coney Island By Barbara Gottlock, Wesley Gottlock The History Press Copyright © 2013 Barbara H. Gottlock and Wesley Gottlock All rights reserved. ISBN: 978-1-62619-103-7 Contents Acknowledgements, Introduction, 1. MANHATTAN, Fort George, 2. STATEN ISLAND, South Beach, Midland Beach, 3. BROOKLYN, Golden City, 4. QUEENS, North Beach, Rockaways' Playland, 5. BRONX, Starlight Park, Clason Point, Freedomland, About the Authors, CHAPTER 1 MANHATTAN FORT GEORGE If one were to list all of Manhattan's varied assets, amusement parks would not be among them. But there was a time, before the island's real estate became so valuable, when a large amusement area flourished for many years. The Fort George amusement area in the Washington Heights section of northern Manhattan was just a short boat ride away from the confluence of the Harlem and Hudson Rivers at Spuyten Duyvil Creek. The creek separates Manhattan and the Bronx. The amusement area is rarely mentioned along with the likes of Coney Island and Palisades Amusement Park. But at its peak, Fort George competed with both of those historic parks. It remains the largest open-air amusement park in Manhattan's history. Perhaps its abrupt demise in 1913, after only an eighteen-year run, denied the area its proper spot in the canon of the amusement industry giants. The term "Fort George" refers to a strategic fortification constructed in northern Manhattan during the American Revolution. Revolutionary soldiers bravely engaged the British from the fort shortly after the Battle of Brooklyn in 1776, allowing General George Washington and his army an escape route to Westchester and New Jersey. Though Washington escaped successfully, the British continued their stronghold in New York City and eventually rebuilt Fort George. With the signing of the Treaty of Paris in 1783, the British abandoned the fort. It will be remembered as the last colonial position to fall on the island of Manhattan. Today, George Washington High School occupies the site. In 1895, on land adjacent to the same hallowed grounds, a large and spectacular amusement area began to evolve. The location was ideal — perched atop cliffs along Amsterdam Avenue starting at 190 Street. Its western boundary was Audubon Avenue. The entertainment zone stretched north up to Fort George Avenue, where the Curve Music Hall was located, though most of the amusement rides were situated a few blocks south. At roughly one thousand feet above sea level, the vistas looking across the Harlem River were breathtaking. Some of the rides were designed to take advantage of the location's natural terrain to enhance thrills. As with most other amusement parks of the era, trolley transportation was crucial. In the case of Fort George, the Third Avenue Railway System, which connected the Bronx to Manhattan, was the conduit. With a terminal near Fort George, the line delivered locals and residents from throughout the city to the park's doorstep for the sum of five cents from most Manhattan locations. The nearby Westinghouse Power and Electric Company provided the electricity for the park using alternating current. Eventually, Con Edison, which used direct current, would buy out Westinghouse. Initially, the amusement area was an amalgam of hastily assembled structures to house sideshows, fortunetellers, smaller rides, shooting galleries, penny arca