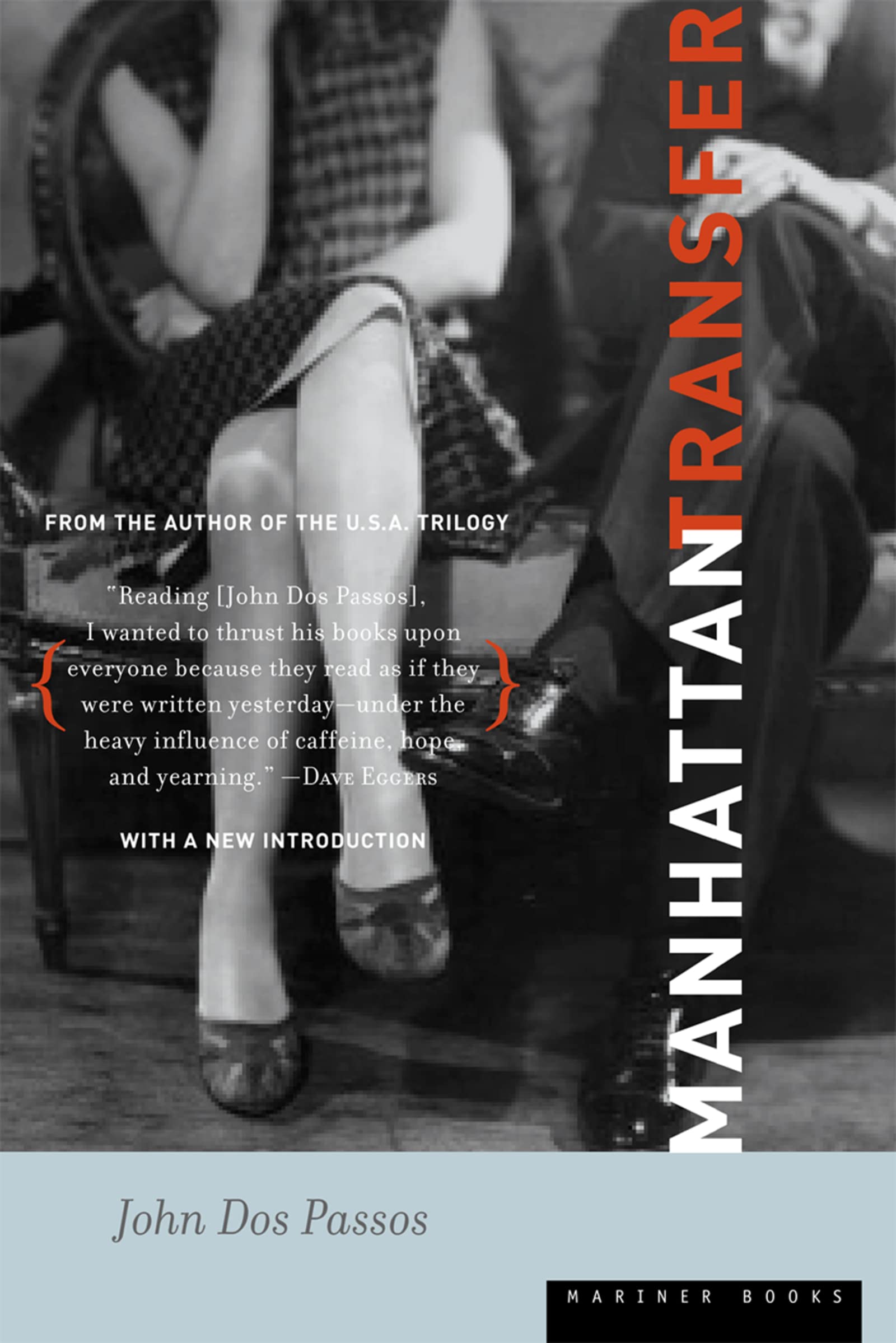

Considered by many to be John Dos Passos's greatest work, Manhattan Transfer is an "expressionistic picture of New York" ( New York Times ) in the 1920s that reveals the lives of wealthy power brokers and struggling immigrants alike. From Fourteenth Street to the Bowery, Delmonico's to the underbelly of the city waterfront, Dos Passos chronicles the lives of characters struggling to become a part of modernity before they are destroyed by it. "A novel of the very first importance" (Sinclair Lewis), Manhattan Transfer is a masterpiece of modern fiction and a lasting tribute to the dual-edged nature of the American dream. "A novel of the very first importance." - Sinclair Lewis John Dos Passos (1896–1970) was a writer, painter, and political activist. His service as an ambulance driver in Europe at the end of World War I led him to write Three Soldiers in 1919, the first in a series of works that established him as one of the most prolific, inventive, and influential American writers of the twentieth century, writing over forty books, including plays, poetry, novels, biographies, histories, and memoirs. Manhattan Transfer By John Dos Passos Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company Copyright © 1925 John Dos Passos All rights reserved. ISBN: 978-0-618-38186-9 Contents Title Page, Contents, Copyright, FIRST SECTION, Ferryslip, Metropolis, Dollars, Tracks, Steamroller, SECOND SECTION, Great Lady on a White Horse, Longlegged Jack of the Isthmus, Nine Days' Wonder, Fire Engine, Went to the Animals' Fair, Five Statutory Questions, Rollercoaster, One More River to Jordan, THIRD SECTION, Rejoicing City That Dwelt Carelessly, Nickelodeon, Revolving Doors, Skyscraper, The Burthen of Nineveh, CHAPTER 1 Ferryslip Three gulls wheel above the broken boxes, orangerinds, spoiled cabbage heads that heave between the splintered plank walls, the green waves spume under the round bow as the ferry, skidding on the tide, crashes, gulps the broken water, slides, settles slowly into the slip. Handwinches whirl with jingle of chains. Gates fold upwards, feet step out across the crack, men and women press through the manuresmelling wooden tunnel of the ferryhouse, crushed and jostling like apples fed down a chute into a press. The nurse, holding the basket at arm's length as if it were a bedpan, opened the door to a big dry hot room with greenish distempered walls where in the air tinctured with smells of alcohol and iodoform hung writhing a faint sourish squalling from other baskets along the wall. As she set her basket down she glanced into it with pursed-up lips. The newborn baby squirmed in the cottonwool feebly like a knot of earthworms. On the ferry there was an old man playing the violin. He had a monkey's face puckered up in one corner and kept time with the toe of a cracked patentleather shoe. Bud Korpenning sat on the rail watching him, his back to the river. The breeze made the hair stir round the tight line of his cap and dried the sweat on his temples. His feet were blistered, he was leadentired, but when the ferry moved out of the slip, bucking the little slapping scalloped waves of the river he felt something warm and tingling shoot suddenly through all his veins. "Say, friend, how fur is it into the city from where this ferry lands?" he asked a young man in a straw hat wearing a blue and white striped necktie who stood beside him. The young man's glance moved up from Bud's roadswelled shoes to the red wrist that stuck out from the frayed sleeves of his coat, past the skinny turkey's throat and slid up cockily into the intent eyes under the brokenvisored cap. "That depends where you want to get to." "How do I get to Broadway? ... I want to get to the center of things." "Walk east a block and turn down Broadway and you'll find the center of things if you walk far enough." "Thank you sir. I'll do that." The violinist was going through the crowd with his hat held out, the wind ruffling the wisps of gray hair on his shabby bald head. Bud found the face tilted up at him, the crushed eyes like two black pins looking into his. "Nothin," he said gruffly and turned away to look at the expanse of river bright as knifeblades. The plank walls of the slip closed in, cracked as the ferry lurched against them; there was rattling of chains, and Bud was pushed forward among the crowd through the ferryhouse. He walked between two coal wagons and out over a dusty expanse of street towards yellow streetcars. A trembling took hold of his knees. He thrust his hands deep in his pockets. EAT on a lunchwagon halfway down the block. He slid stiffly onto a revolving stool and looked for a long while at the pricelist. "Fried eggs and a cup o coffee." "Want 'em turned over?" asked the redhaired man behind the counter who was wiping off his beefy freckled forearms with his apron. Bud Korpenning sat up with a start. "What?" "The eggs? Want em turned over or sunny side up?" "Oh su