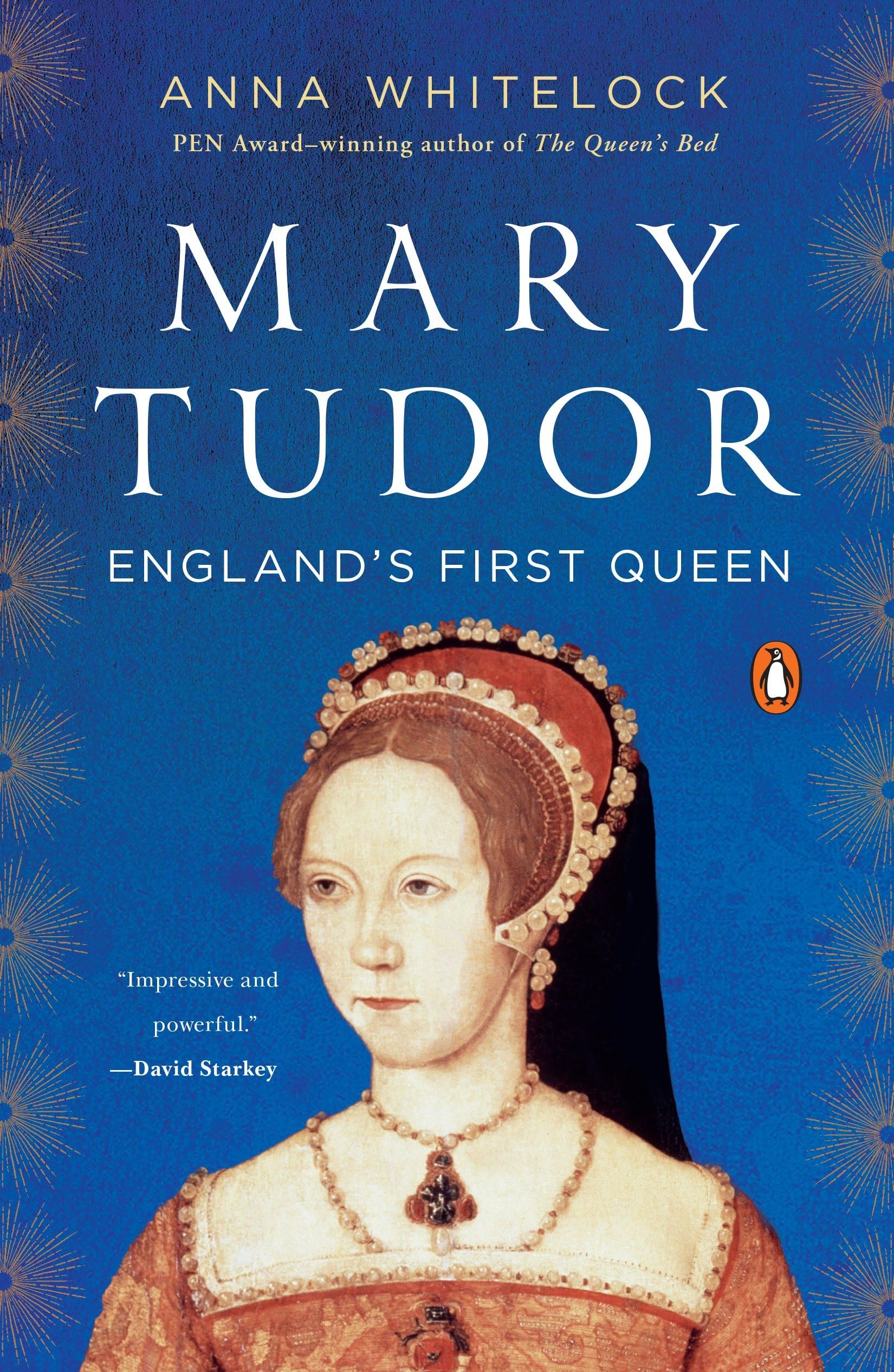

An engrossing, unadulterated biography of “Bloody Mary”—elder daughter of Henry VIII, Catholic zealot, and England’s first reigning Queen Mary Tudor was the first woman to inherit the throne of England. Reigning through one of Britain’s stormiest eras, she earned the nickname “Bloody Mary” for her violent religious persecutions. She was born a princess, the daughter of Henry VIII and the Spanish Katherine of Aragon. Yet in the wake of Henry’s break with Rome, Mary, a devout Catholic, was declared illegitimate and was disinherited. She refused to accept her new status or to recognize Henry’s new wife, Anne Boleyn, as queen. She faced imprisonment and even death. Mary successfully fought to reclaim her rightful place in the Tudor line, but her coronation would not end her struggles. She flouted fierce opposition in marrying Philip of Spain, sought to restore England to the Catholic faith, and burned hundreds of dissenters at the stake. But beneath her hard exterior was a woman whose private traumas of phantom pregnancies, debilitating illnesses, and unrequited love played out in the public glare of the fickle court. Though often overshadowed by her long-reigning sister, Elizabeth I, Mary Tudor was a complex figure of immense courage, determination, and humanity—and a political pioneer who proved that a woman could rule with all the power of her male predecessors. “An impressive and powerful debut.” —David Starkey “This roller coaster of a story is told by Whitelock with great verve and pace.” —Antonia Fraser “Impressive . . . an unforgettable picture of Mary . . . [Whitelock] gives us a woman who met impossible challenges with courage and conviction.” — Financial Times “Whitelock blazes through the Protestant burnings that earned her the name ‘Bloody Mary’ and excels in her timely portrait of a religious fanatic.” —The Sunday Times Anna Whitelock is a historian of Tudor England and the author of The Queen’s Bed: An Intimate History of Elizabeth’s Court , winner of the PEN/Jacqueline Bograd Weld Award for Biography. She teaches early modern history at Royal Holloway College, University of London, and is the director of the university’s Centre for Public History, Heritage, and Engagement with the Past. A frequent media commentator on the Tudors, the monarchy, and royal succession, she has written for the Guardian , the Times Literary Supplement , and BBC History . Chapter One PRINCESS OF ENGLAND Mary, the daughter of king henry viii and katherine of Aragon, was born at four in the morning of Monday, February 18, 1516, at Placentia, the royal palace at Greenwich, on the banks of the Thames River in London. Three days later, the nobility of England gathered at the royal apartments to form a guard of honor as the baby emerged from the queen's chamber in the arms of Katherine's devoted friend and lady-in-waiting, Elizabeth Howard, countess of Surrey. Beneath a gold canopy held aloft by four knights of the realm, the infant was carried to the nearby Church of the Observant Friars.1 It was the day of Mary's baptism, her first rite of passage as a royal princess. The procession of gentlemen, ladies, earls, and bishops paused at the door of the church, where, in a small arras-covered wooden archway, Mary was greeted by her godparents, blessed, and named after her aunt, Henry's favorite sister. The parade then filed two by two into the church, which had been specially adorned for the occasion. Jewel-encrusted needlework hung from the walls; a font, brought from the priory of Christchurch Canterbury and used only for royal christenings, had been set on a raised and carpeted octagonal stage, with the accoutrements for the christening--basin, tapers, salt, and chrism--laid out on the high altar.2 After prayers were said and promises made, Mary was plunged three times into the font water, anointed with the holy oil, dried, and swaddled in her baptismal robe. As Te Deums were sung, she was taken up to the high altar and confirmed under the sponsorship of Margaret Pole, countess of Salisbury.3 Finally, with the rites concluded, her title was proclaimed to the sound of the heralds' trumpets: God send and give long life and long unto the right high, right noble and excellent Princess Mary, Princess of England and daughter of our most dread sovereign lord the King's Highness.4 Despite the magnificent ceremony, the celebrations were muted. This was not the longed-for male heir, but a girl. Six years earlier, in the Church of the Observant Friars, Henry had married his Spanish bride, Katherine of Aragon. Within weeks of the wedding, Katherine was pregnant and Henry wrote joyfully to his father-in-law, Ferdinand of Aragon, proclaiming the news: "Your daughter, her Serene Highness the Queen, our dearest consort, has conceived in her womb a living child and is right heavy therewith."5 Three months later, as England awaited the birth of its heir, Katherine miscarried. Yet the news was not made publ