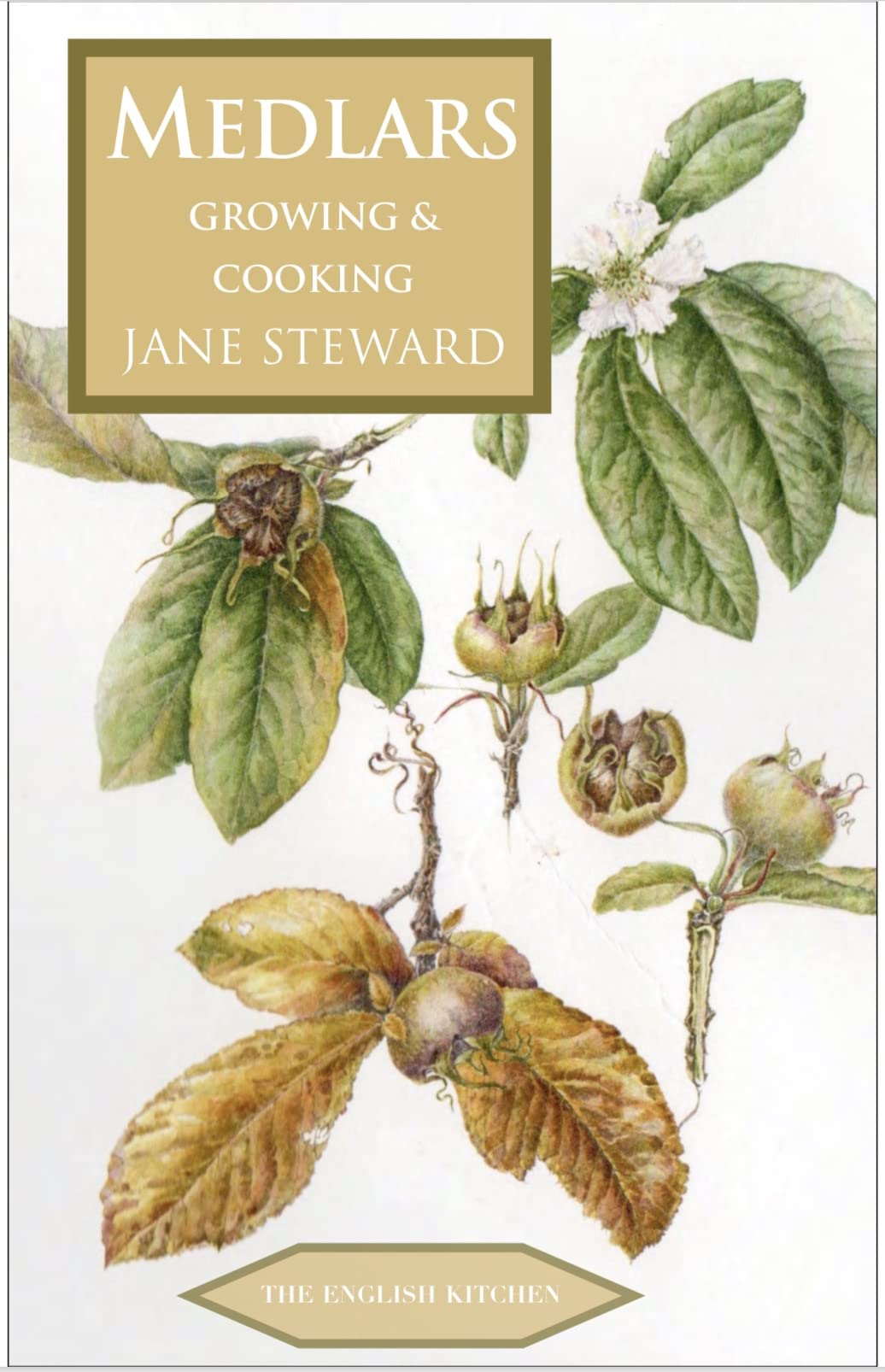

At Eastgate in rural North Norfolk, Jane Steward is reviving the medlar, an old English fruit which was once Britain’s sweet treat. Her trees are alive with colour for much of the year: white and yellow flowers in the summer, green leaves that turn to gold and russet. Grafted onto quince A rootstock, and helped by local honey bees, these are trees with prolific fruit. Alongside the Nottingham variety of medlars, Jane has established a national culinary collection on her six-acre smallholding. Varieties include Breda , Dutch, Westerveld, Macrocarpa, Royal, Bredase Reus, Flanders Giant, Iranian medlars. Her book on medlars will have over 30 recipes alongside a myriad of information on this forgotten fruit. The Story of the Medlar If the medlar had a golden age in England, it was probably between the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries. . While don’t know, for example, how often Henry VIII ate them, but he certainly received at least two batches of medlars between 1529 and 1532. In an account of the expenses paid from the privy purse during that period, we find the following for November 1531: Itm the xviij daye paied to the gardyner at hampton co’te for bringing peres and medelers to the Kings grace. vij s. vj d.” In October the following year, Henry took Anne Boleyn to France, where he met the French king, Francis I. Henry was hoping, among other things, to persuade Francis to use his influence with the Pope to help him secure an annulment of his marriage to Catherine of Aragon. In 1898, P.A. Hamy published a book about their interviews. He quoted ordinances and lists of provisions for Calais, where the English entertained the French. Among the sumptuous supplies of swans, geese, capons, ducks and larks were large quantities of medlars. One list, for the two kings and their trains for four meals, included four hundred dozen pears and the same number of medlars ( middlers ). In another list, medlars appeared alongside their close cousins, apples and pears. In her book A history of gardening in England , the botanist Alicia Amherst, 1865-1941, wrote that John Chapman, Henry VIII’s head gardener at Hampton Court Palace, laid out a new orchard for him. This was to the north of the old gardens, with fruit trees such as medlar, pear, damson, cherry and apple. Henry had acquired the property, and inherited Chapman, from Cardinal Wolsey in 1528, the Cardinal having fallen from royal favour after his failure to secure the desired annulment of Henry’s marriage. Referring to fruit generally, Joan Morgan and Alison Richards explain that royal example ‘helped to stimulate consumption in fashionable circles, which in turn led to the establishment of new orchards to supply the metropolis’, especially in Kent. In this way, Henry’s taste for medlars may have helped to popularise them in the upper echelons of society. Also writing on this subject in the twentieth century, Miles Hadfield, a botanical artist and garden historian, was the first president of the Garden History Society. In 1976, he listed Mespilus germanica as one of the trees which were ‘widely planted in the great period of British landscape gardening and earlier’. It had been introduced, he noted, before 1548. As such, it was ‘a very early introduction’. The Elizabethan trend for planting orchards and kitchen gardens continued in the early years of the seventeenth century. John Tradescant (father) started as head gardener to Sir Robert Cecil, the first Earl of Salisbury, at Hatfield House in Hertfordshire. He had already obtained for his garden medlar, quince, walnut and cherry trees from a grower named Henrich Marchfeld. A couple of years later he sent Tradescant to the Low Countries to buy more stock. The gardener kept accounts of his purchases and expenses, from which we can see what plants he bought and where. They are described in Mea Allan’s 1964 book about the Tradescants. Tradescant crossed by ship from Gravesend to Flushing at the beginning of October. From there, he travelled to Leiden, via Middleburg, Rotterdam and Delft. After purchasing, among other things, roots of flowers and roses, he moved on to Haarlem, to buy trees. At Delft, he acquired a variety of fruit trees from the nurseryman Dirryk Hevesson. He purchased ‘two great medlar trees’ for 4s 0d and ‘two great medlar trees of naples’ for 5s 0d. Referring generally to the prices which he paid for plants, Mea Allan considers it certain that he didn’t buy anything that could be obtained in England: ‘These entries of costly fruits and plants are therefore valuable records of first introductions to this country’. Ms Allan suggests that this was the earliest record of the great medlar tree of Naples and that it was ‘evidently our large Dutch medlar’. If, however, it was the medlar of Naples which had been described in John Gerard’s herbal of 1597 and was later to appear in John Parkinson’s books of 1629 and 1640, it’s likely to have